Texts, photographs, links and any other content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.

FIRST IN A SERIES ON THE 30 YEARS SINCE THE END OF USSRColin Hardage, is soon to complete his Bachelor's of Arts degree at the American University of Paris.

Spring 2021 - Issue 6 of N&C - Nature & Cultures, a special issue on the past 30 years of the history of former republics of the USSR , will feature stories on Russia, Ukraine, the Orthodox Church and the political events in Central and Eastern Europe between the mid 1980s and 1991.

|

here is no denying that the turn from the 1980s to the 1990s marked a consequential period in human history. The Cold War, which had spanned the better part of five decades during which the world had been on the brink of World War III – and, by extension, the potential extinction of humanity – came to an end with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. The import of these events, widely unexpected by outsiders at the time, generated extensive research aimed at discerning the causes of the collapse. The focus has been primarily on factors such as economic stagnation, political repression, bureaucratic bloat, and rising nationalism. However, even as early as the events were still unfolding, a few specialists began arguing that other factors – such as widespread environmental degradation within Eastern Bloc countries – played a larger role than they are typically given credit for, and literature on the subject has been accumulating for the past three decades. In fact, some of the most privileged actors and observers of the events of 1989-1991 have even argued that it might have been the primary factor in the bloc’s collapse. On the thirtieth anniversary of the end of the Soviet Union, it is legitimate to analyze this argument.

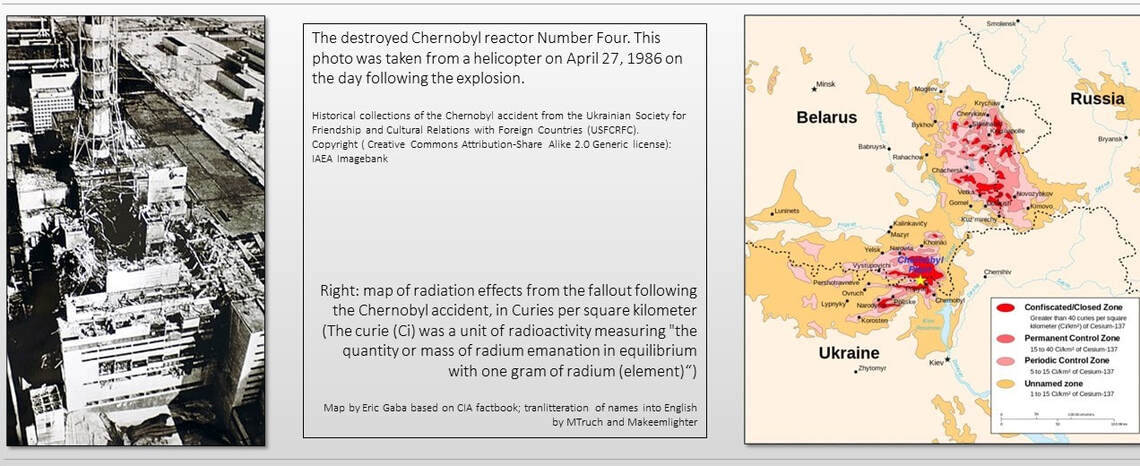

Chernobyl: the tip of the iceberg

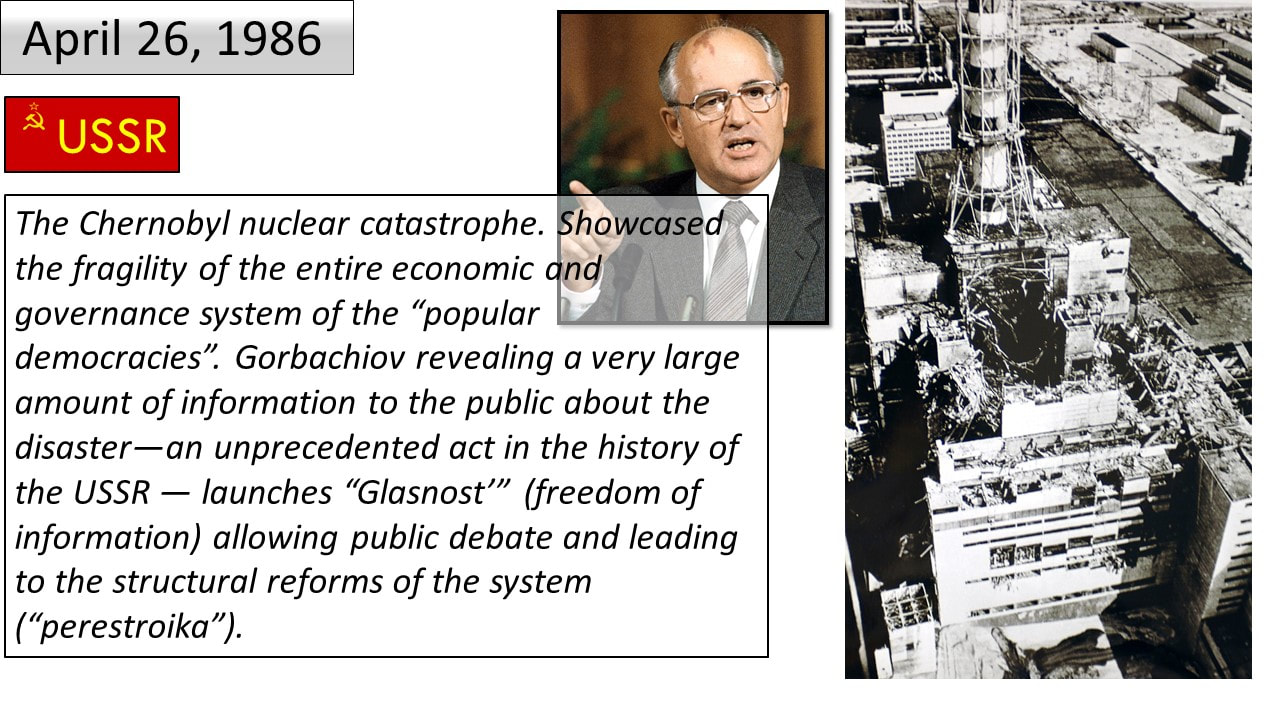

Denying that the ecosystems of states in the Eastern Bloc degraded catastrophically under communist rule became entirely impossible after the Chernobyl explosion. While the event came as an unexpected shock to inhabitants of the entire planet, as well as those of the “peoples’ democracies”, a few lone voices of dissent – the first Central and Eastern European environmentalists – had already warned that the communist regimes of Eastern Europe were slipping towards large-scale destruction.

Communist regimes typically paid at least lip service to environmental concerns, at times designating large areas of land as national parks and accusing capitalist countries of “predatory” exploitation of nature. But the demand for rapid industrialization prioritized by government ideology and planning, which focused, for example, on the production of coal and steel – what was known as “smokestack industrialization” – and “the myth of a new nature” that could be controlled and reshaped by man, ultimately resulted in a general lack of care towards the environment (Kirchhof 152; Kobtzeff 4-5).

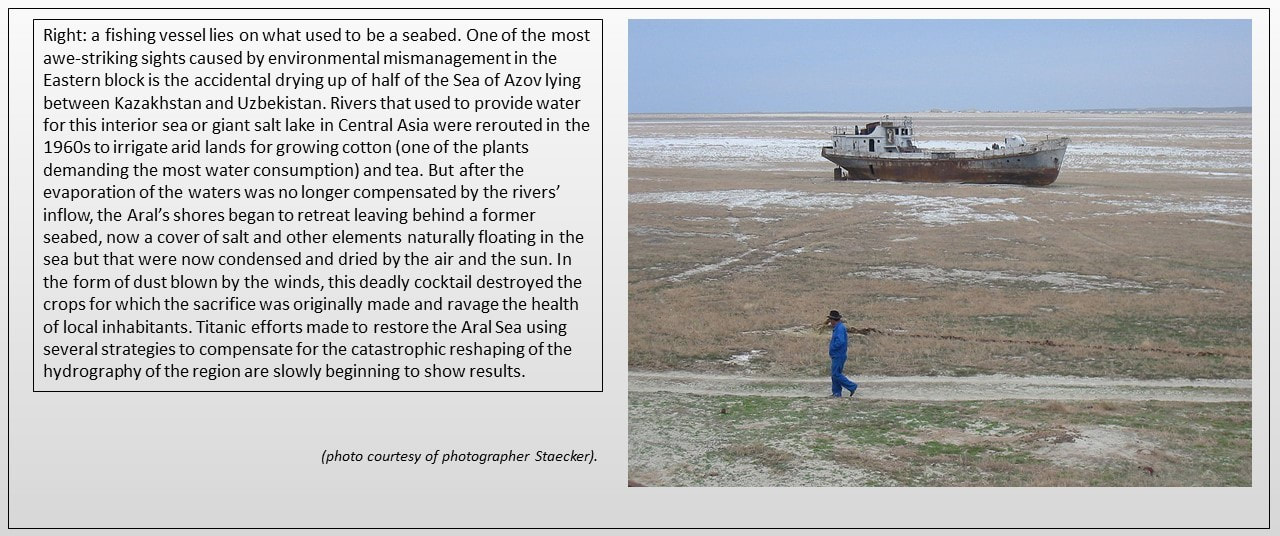

Industrial pollution – which was inevitable given the heavy industry relentlessly emphasized by economic planners – was poorly controlled if controlled at all. Natural resources were harvested at unsustainable rates, and ambitious but unfeasible projects like Stalin’s “Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature” and Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands campaign ultimately had vastly detrimental effects on the environment, some of which – most obviously the desertification of the Aral Sea – we are still dealing with today (Brian 672; Kiessling 560).

By the 1980s, the state of environmental degradation in the Eastern Bloc was easily visible to the average citizen. In East Germany, between 1980 and 1991, five million tons of sulfur dioxide were released annually as a result of the burning of lignite coal; in Poland, from 1980 to 1985, nitrogen oxide emissions rose from 187,000 tons per year to 670,000 tons (Schreiber 361-362). 35% of Polish industrial facilities had no wastewater treatment processing capabilities whatsoever, and by 1991, 95% of surface water in Poland was unsafe for human consumption (366). In neighboring East Germany, 66% of the country’s waterways were classed as “inadmissibly polluted” by 1968 (Kirchhof 155). By the mid-1980s, pollution in the Danube was so severe in Hungary and Romania that river water was capable of rapidly degrading metal pipes; by the end of the decade, 80% of agricultural land in Bulgaria, 54% of agricultural land in Czechoslovakia, and 30% of agricultural land in Hungary and Romania was at risk of becoming unusable (Kobtzeff 7). In certain “hot spots” of environmental degradation in the Soviet Union, cancer rates were as much as 50% higher than the national average (Schreiber 364); in Bulgaria, lung disease rates jumped up from 969 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 1975 to 17,386 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 1985; in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, deaths due to vascular disease increased by 42% from 1981 to 1985 and infant mortality rose by 65.2% from 1960 to 1985; rates of circulatory diseases, cancers, and respiratory diseases were 155%, 30%, and 47%, respectively, above the national average in the industrial Upper Silesia region of Poland (Kobtzeff 8-9).

Even in those areas of environmental protection where action was undertaken, there were sometimes glaring, and consequential, omissions; water quality monitoring in the Lithuanian SSR was relatively comprehensive compared to many other parts of the Eastern Bloc, but wastewater treatment plants in that Soviet Republic did not remove nitrogen or phosphorous, leaving Lithuanian rivers vulnerable to eutrophication (Kirchhof 46). With environmental degradation so widespread and so severe, it was only inevitable that the general public would take note.

With increasingly large sectors of the population subjected to the consequences of environmental degradation, the situation became impossible to conceal and, under these circumstances, it is perhaps unsurprising that environmentalist movements arose in many Eastern European countries. From January 1978, Christian ecologists emerging from the East German pacifist movement, tolerated by the regime due to their opposition to NATO forces and nuclear missiles in West Germany, began to organize (Kobtzeff 20); in neighboring Poland, the Krakow-based Polish Ecology Club was a prominent environmental advocacy group (Kirchhof 160-161), and thesis sixteen of the September 1981 Gdansk program of Solidarnosc explicitly stated that the union would seek environmental protection (Kobtzeff 21). In Bulgaria, the leading environmentalist movement was called Ecoglasnost (25); Czechoslovakia had two major ones, the Slovak Union of the Defenders of Nature and Landscape and Czech Union of the Defenders of Nature (18); Hungary had a veritable litany of groups arising from the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros dam controversy (Kobtzeff 23). Within Yugoslavia, communist though not a part of the Soviet sphere, Slovenia served as the foremost hotbed of environmentalist opposition (21), but militant environmentalism was present in the country, the Svarun movement in Croatia and Montenegro, for example, where it opposed the project for damming the Tara River (Kirchhof 179-180). With the adoption of glasnost’ by the Soviet Union under Gorbachev (alternatively spelled Gorbachiov which is closer to the pronunciation of the name) (157), coinciding with the fallout of the 1986 Chernobyl catastrophe (Kobtzeff 24), environmental awareness and militant action only grew and accelerated, becoming a major force of opposition to the poor environmental policies of Eastern Bloc regimes.

The Collapse: An Environmental Reckoning, or a Sociopolitical one?

Whether environmental degradation was the essential cause of the fall of the Soviet-type regimes, the other factors most commonly ascribed to the demise of the Eastern Bloc – economic stagnation, political repression, government incompetence or inefficiency, previously-suppressed nationalism – are far from negligible.

In 1951, the per capita GDP of Eastern Europe was 51% of that of Western Europe; by 1973, it had fallen to 47%, and by 1989, it was only 40%. Channels of information such as the samizdat press or the growing reach of radio and television broadcasting from the West – which could not be stopped at the borders, as jamming would have affected viewers in the countries where the broadcasting originated, which would have raised suspicions among otherwise sympathetic left-wingers and potentially come across as an act of trans-border aggression – made it increasingly obvious to the populations in the Eastern Bloc that they were indeed falling behind (McDermott 5). An emphasis on heavy industry – in investment and allotment of resources, in wages offered to workers, in research and development – meant a constant paucity of consumer goods; that which was produced was highly standardized and, oftentimes, of dubious quality (Gronow 57; Smith; Kaiser). Inefficiency was rife as a result of centralized economic planning, particularly in agriculture, which forced the Soviets to import grain from their arch-rival, the United States (Miller 116). As economic performance sagged, Eastern Bloc countries struggled to keep their budgets in shape, leaving them struggling to match Western military and R&D developments; under such circumstances the Eastern Bloc regimes felt a need to cease projecting power as they once had and turn inwards, particularly after the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan (McDermott 5-6). Preceded by works such as Georges Bortoli’s Vivre à Moscou (To Live in Moscow), permanent correspondents such as Robert Kaiser of the Washington Post and Hedrick Smith of the New York Times wrote extensive reports on living conditions in the Soviet Union that became blockbusting bestsellers in the West. Smith’s The Russians was particularly influential and is now a classic which, as the decades go by, is gaining increasing value as a source for everyday life in the Soviet Union and the extent of the decay of its economy and governance. Such publications also reached the public of the Soviet bloc through militant dissidents living west of the Iron Curtain, or through black market smugglers.

Political repression had been rife within the Marxist-Leninist countries of the Eastern Bloc for the entirety of their existence, and the number of victims of repression or surveillance increased endlessly. Every country in the bloc had its own “security service” aimed at monitoring and controlling not only known dissidents but all citizens, always suspected of harboring potential reasons for dissident – the Soviet Union’s KGB, Romania’s Securitate, East Germany’s Stasi, Bulgaria’s KDS, Hungary’s AVH, Poland’s SB, Yugoslavia’s UDBA, Albania’s Sigurimi. Some of these agencies – particularly the Stasi, Securitate, and Sigurimi – remain infamous today for the stringency and omnipresence of their surveillance, which rivalled that of the Stalin-era NKVD. The sudden and unexpected publication of Aleksander Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago in Paris in 1973, which provoked Solzhenitsyn’s arrest and expulsion from the USSR, caused a scandal not so much because it described the extent of repression and degree of horror inflicted upon its victims, but mostly because its historic inquiry presented evidence that the repressions began well before Stalin came to power, shattering the myth of “Stalinist” repressions limited to the rule of one particular dictator, and – especially embarrassing to the Soviet authorities – continued, although not as violently and extensively, well into the 1960s.

The combination of economic stagnation and political oppression could only breed opposition. This opposition emerged even in the ranks of the ruling parties; as is demonstrated by Solzhenitsyn’s work, or by a simple study of the biographies of the great majority of government officials between 1930 and 1968, the more one climbed the ladder of the Party hierarchy, the more one risked ending in jail or dead.

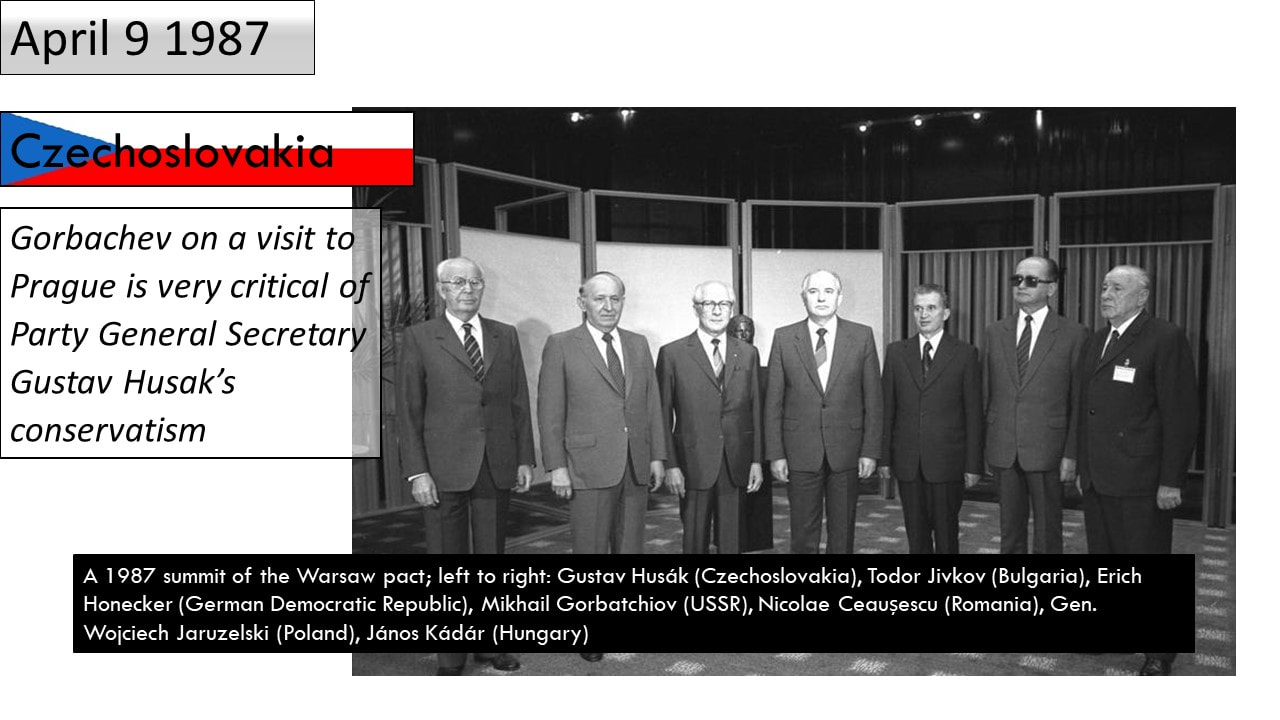

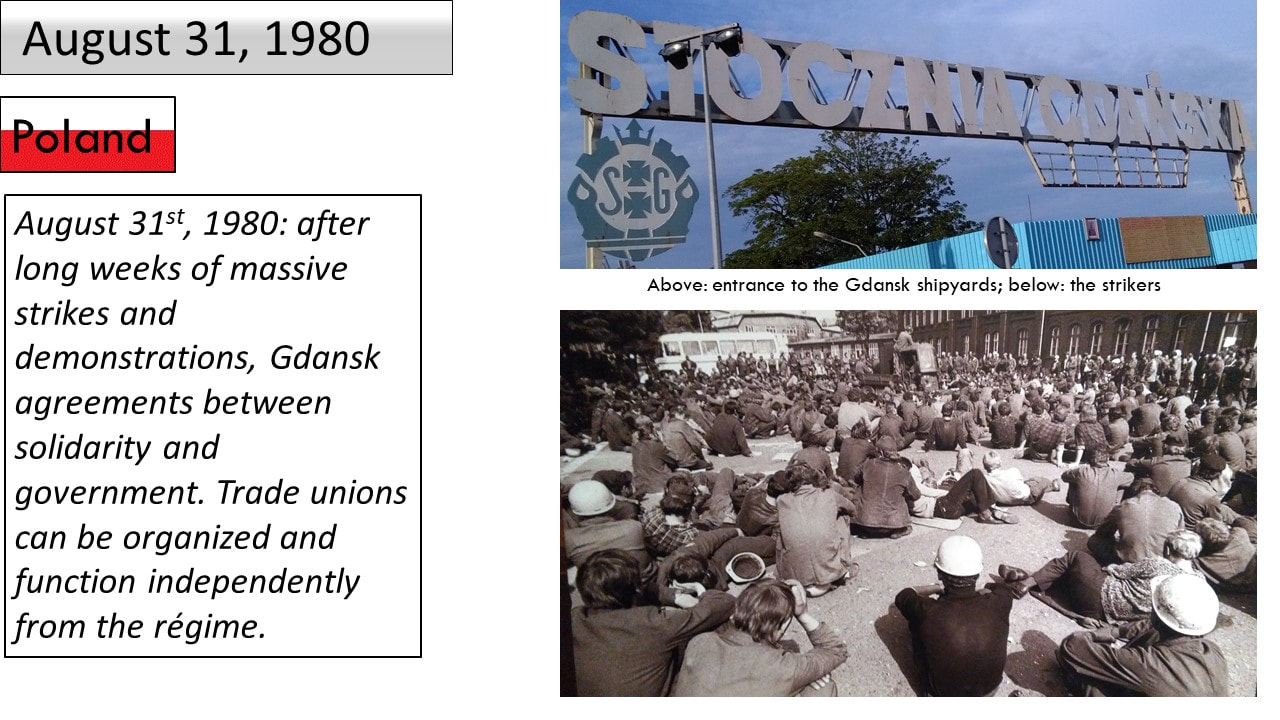

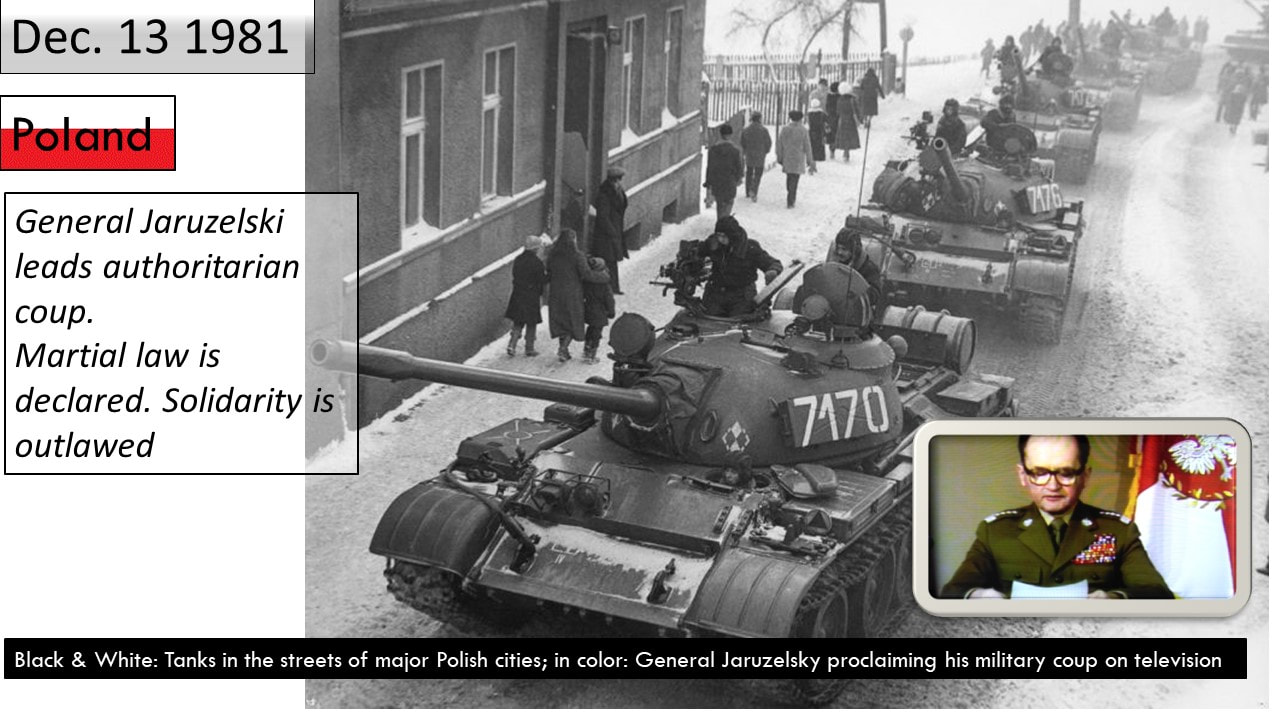

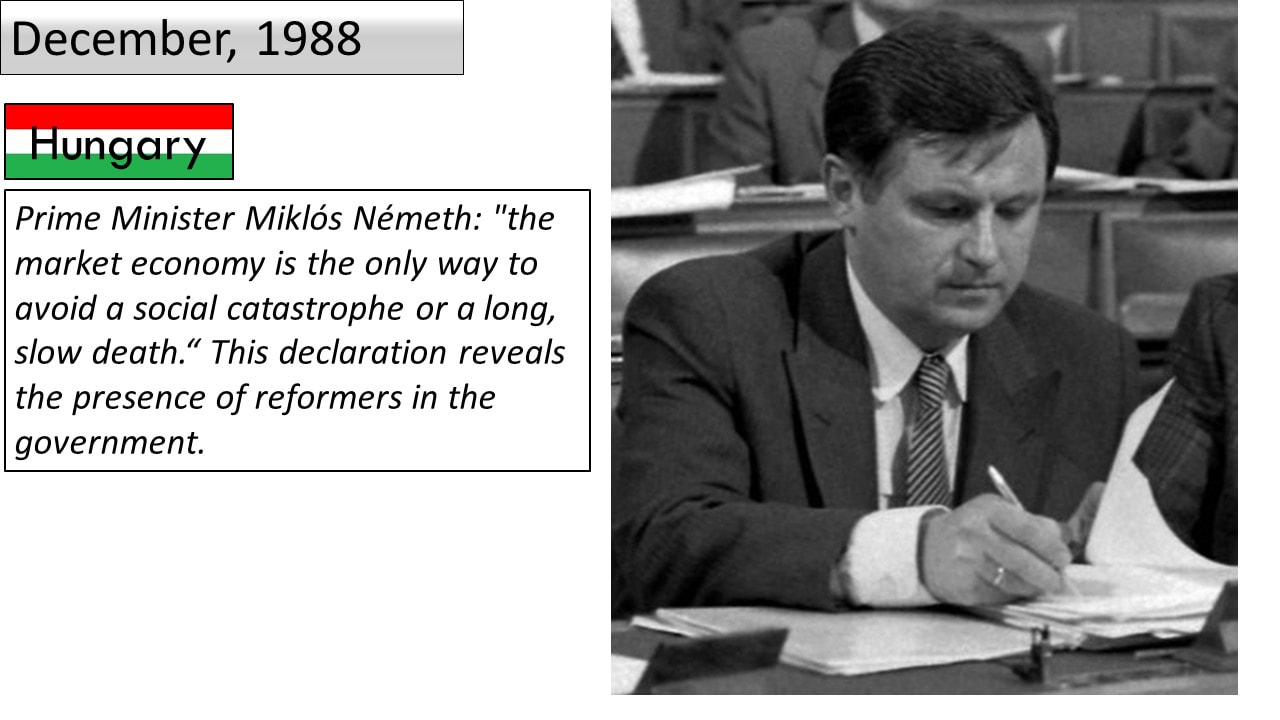

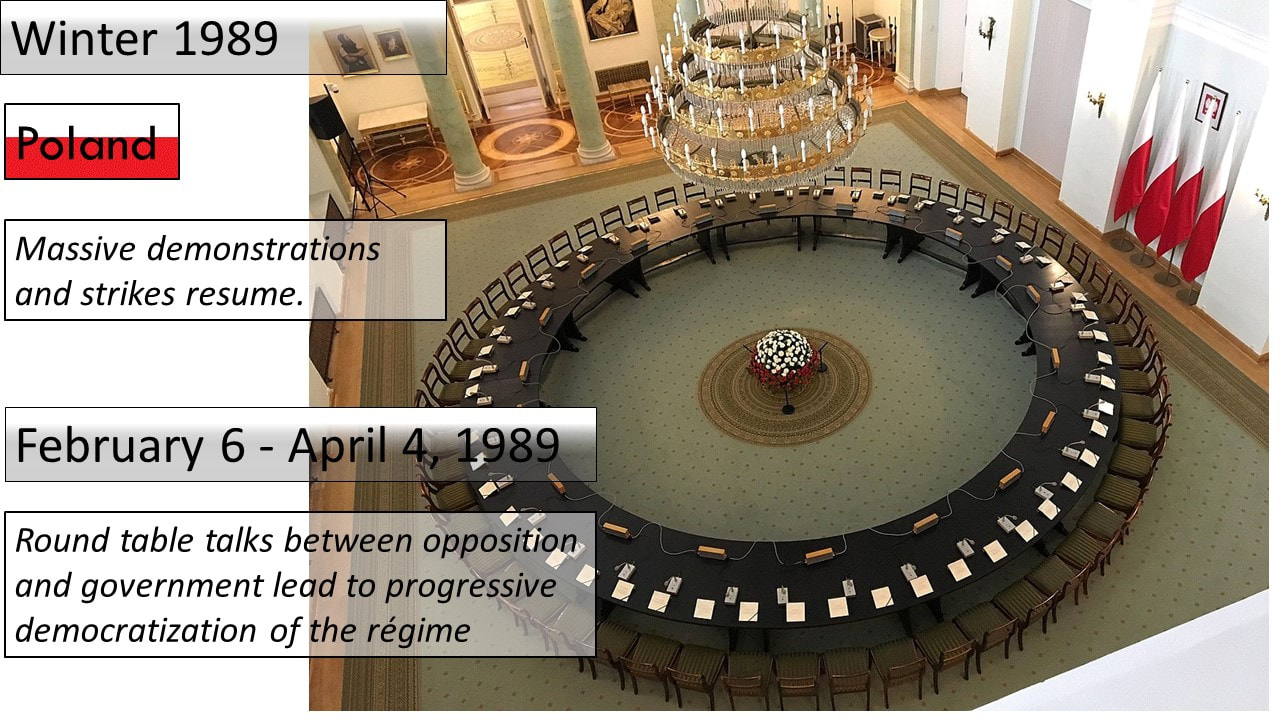

And if opposition had emerged even among the ruling classes, it was inevitable that it would emerge among the general public. Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, the IFM and Working Group for GDR Citizenship Rights in East Germany, looser associations of dissidents in Hungary, and fiercely-suppressed efforts at organization in Romania all stand as testament to this fact (McDermott 7-8). The country that ultimately led the way, however, would be Poland, where the Solidarity trade union became a major political force. The Soviet Union itself ultimately evolved under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, whose policies of glasnost’ and perestroika allowed for broader expression of dissent within the Soviet Union meant not to become a norm but to put pressure on aging hardline leaders in the entire Eastern Bloc and eventually replace them with individuals willing to undertake reform in order to save the Socialist system.

And if opposition had emerged even among the ruling classes, it was inevitable that it would emerge among the general public. Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, the IFM and Working Group for GDR Citizenship Rights in East Germany, looser associations of dissidents in Hungary, and fiercely-suppressed efforts at organization in Romania all stand as testament to this fact (McDermott 7-8). The country that ultimately led the way, however, would be Poland, where the Solidarity trade union became a major political force. The Soviet Union itself ultimately evolved under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, whose policies of glasnost’ and perestroika allowed for broader expression of dissent within the Soviet Union meant not to become a norm but to put pressure on aging hardline leaders in the entire Eastern Bloc and eventually replace them with individuals willing to undertake reform in order to save the Socialist system.

Amidst all this, within the Soviet Union, populations long subjected to unwilling rule from Moscow began to dabble openly with the concept of claiming or reclaiming their independence. The Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia had obtained independence from the Russian Empire in 1918 only to have it snatched away with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact; in the 1980s, Baltic nationalist popular fronts rose in prominence within the three Baltic countries and, furthermore, “consciously attempted to reproduce themselves throughout the Soviet Union”, aiding in the growth of similar nationalist movements in Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, and Moldova (Beissinger 340-341). Nationalist desires also played a role in East Germany, where the idea of reunification with West Germany gained increasing traction and, rather infamously, in Yugoslavia.

From here, with all the factors in place, the dominoes begin to fall. Once demonstrations gather such crowds that not even heavily armed troops in large numbers can control them, governments are forced to negotiate if they do not want civil war.[i] In April 1989, the Polish government was under the pressure of such massive strikes and demonstrations that it entered roundtable talks with Solidarity, which would win a crushing victory that June in the newly reformed semi-free snap elections. On June 27th, the foreign ministers of Austria and Hungary symbolically cut open a section of fencing on their border, opening the Iron Curtain. On August 23rd, the “Baltic Way” protest saw 2 million Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians – more than one third of the total population of all three countries – form a human chain across the length of the Baltic countries; the following day, Solidarity formed a non-communist government in Poland. On November 9th, following the bungling of a press conference by an East German official, the Berlin Wall was opened and, over the following months, dismantled. On Christmas Day, 1989, Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife were executed after the only violent uprising in this series of regime changes; four days later, dissident leader Vaclav Havel became Czechoslovakia’s president (“1989”). On March 11th, March 30th, and May 4th of 1990, Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia respectively declared independence (Hiden 162-163). On February 2nd, 1990, a non-communist regime came to power in Bulgaria; on March 18th, the same occurred in East Germany; on March 25th, in Hungary. On October 3rd, Germany was formally reunified. A desperate attempt by Soviet hardliners in August 1991 to save the USSR through a military coup against Gorbachev had the opposite of its intended effect, and on December 8th, 1991, the leaders of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine declared the Soviet Union to be dissolved.

Connections: The Correlation of Sociopolitical & Environmental Factor.

Obviously, there is an abundance of statistical and other evidence to back up both the traditional narrative, with its focus on economic and political factors, and a narrative placing increased emphasis upon environmental degradation as a factor. Perhaps, ultimately, the conclusion to be drawn from this is that the two narratives are not at odds at all. Della Porta, in exploring the causes for the Eastern Bloc’s collapse, warns against “immaculate conception syndrome” – the perception, common when one is in the process of observing or writing about an ongoing or recently-concluded revolution, that it has sprung into existence from thin air (Della Porta 38). Instead, she writes, new movements tend to develop from previous movements that have managed to arise or persist even under authoritarian conditions, which provide a foundation of organization that can be built upon; these movements then “appropriate opportunities” to push their newer, broader agendas, in some cases ultimately culminating in revolution (46).

This is the crucial role that was played by environmental causes and environmentalist groups in the fall of the Eastern Bloc. The regimes of the Eastern Bloc, while repressive and authoritarian on the whole, did provide some leeway domestically for environmentalist groups, and – even more consequentially – allowed for international organization of these groups (Della Porta 41). This was because these regimes did feel a need to pay lip service to ecological concerns, and hoped that the energy of environmentalist groups would be directed towards the West, or redirected into state-approved groups like East Germany’s Gesellschaft für Natur und Umwelt and Poland’s Liga Ochrony Przyrody (Kirchhof 156). It was also widely believed by state security services in the Eastern Bloc that the appeal of environmental groups was limited in nature (157) – an assessment that became increasingly untrue as the state of environmental degradation became more obvious to the general public, and which ignored the potential for these national and international environmentalist networks to broaden beyond exclusively ecological concerns.

This, ultimately, is exactly what happened – the networks built to advance environmental concerns provided the framework for newer, larger networks that sought to advance economic and political concerns, which ultimately led to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Most examples of environmental movements provided in the first chapter of this paper can be linked to the events and movements outlined in the second chapter. The networks established by East German Christian ecologists played an important role in the demonstrations that ultimately brought about German reunification. Thesis sixteen of Solidarity’s official program proves the link between environmental concerns and economic and political concerns in the main driving force of the 1989 revolutions in Poland. Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia had extensive overlap with Czech and Slovak environmentalist organizations (Kirchhof 147); Ecoglasnost was a leading force in protests in Bulgaria (Kobtzeff 25). Slovenia, hotbed of environmentalist protest within Yugoslavia, was the first of the Yugoslav republics to declare independence from Belgrade. And even if the movement towards independence in the Baltic was not so directly derived from environmental movements, the fashion by which Baltic movements organized similar movements laterally elsewhere in the Soviet Union is reminiscent of how environmentalist groups organized internationally across the Eastern Bloc.

This, ultimately, is exactly what happened – the networks built to advance environmental concerns provided the framework for newer, larger networks that sought to advance economic and political concerns, which ultimately led to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Most examples of environmental movements provided in the first chapter of this paper can be linked to the events and movements outlined in the second chapter. The networks established by East German Christian ecologists played an important role in the demonstrations that ultimately brought about German reunification. Thesis sixteen of Solidarity’s official program proves the link between environmental concerns and economic and political concerns in the main driving force of the 1989 revolutions in Poland. Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia had extensive overlap with Czech and Slovak environmentalist organizations (Kirchhof 147); Ecoglasnost was a leading force in protests in Bulgaria (Kobtzeff 25). Slovenia, hotbed of environmentalist protest within Yugoslavia, was the first of the Yugoslav republics to declare independence from Belgrade. And even if the movement towards independence in the Baltic was not so directly derived from environmental movements, the fashion by which Baltic movements organized similar movements laterally elsewhere in the Soviet Union is reminiscent of how environmentalist groups organized internationally across the Eastern Bloc.

Indeed, as the Iron Curtain finally crumbled in 1989, a common quip in many Eastern European countries proclaimed that revolution “took 10 years in Poland, 10 months in Hungary, 10 weeks in East Germany, and 10 days in Czechoslovakia” (“The Curtain Rises”) – a process that likely occurred, at least in part, because Eastern Bloc regimes had allowed a transnational network to develop between environmental groups, and this network, like the various domestic networks, could be repurposed or built upon to advance calls for economic and political reform. Once the first Eastern Bloc regime fell, this network ensured that other regimes would meet the same fate.

In this sense, even if environmental issues were not the causes which pushed most people into the street in protest, or the causes which most directly precipitated the fall of Eastern Bloc regimes, they were, more often than not, those causes which resulted in the creation of organizational frameworks that other causes were subsequently able to use, and which allowed for the toppling of these regimes to become a case of the domino effect. Environmentalism provided a framework upon which demands for economic and political change could be – and were – built.

In this sense, even if environmental issues were not the causes which pushed most people into the street in protest, or the causes which most directly precipitated the fall of Eastern Bloc regimes, they were, more often than not, those causes which resulted in the creation of organizational frameworks that other causes were subsequently able to use, and which allowed for the toppling of these regimes to become a case of the domino effect. Environmentalism provided a framework upon which demands for economic and political change could be – and were – built.

In the process of writing this article, I have been reminded at several points during its writing of the HBO miniseries Chernobyl. While not perfectly accurate to the history, it is an eminently compelling and well-crafted narrative. In particular, I have been reminded of a line delivered by Jared Harris, playing the role of Professor Valery Legasov:

“When the truth offends, we lie and lie until we can no longer remember it is even there, but it is still there. Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later, that debt is paid.”

We are well-acquainted with the economic and political lies that the Soviet Union and its satellite states told, the propaganda posters with fabricated Stakhanovite numbers, the jokes about queues and shortages and mediocre products, the use of “whataboutism” to deflect criticism of political repression. But these regimes also told lies about their commitment to conservationism and ecology, and about the state of the environment in their countries – not only about great catastrophes such as Chernobyl, but about thousands of minor acts of negligence that slowly added up – and allowed environmental groups to organize out of the belief that they would never be called out on it.

Eventually, however, the truth about environmental degradation in the Eastern Bloc became undeniable, and these environmental groups provided the foundation for these regimes to be called out on their lies – not only their environmental lies, but their economic and political lies, too.

And in the end, the debt was paid.

“When the truth offends, we lie and lie until we can no longer remember it is even there, but it is still there. Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later, that debt is paid.”

We are well-acquainted with the economic and political lies that the Soviet Union and its satellite states told, the propaganda posters with fabricated Stakhanovite numbers, the jokes about queues and shortages and mediocre products, the use of “whataboutism” to deflect criticism of political repression. But these regimes also told lies about their commitment to conservationism and ecology, and about the state of the environment in their countries – not only about great catastrophes such as Chernobyl, but about thousands of minor acts of negligence that slowly added up – and allowed environmental groups to organize out of the belief that they would never be called out on it.

Eventually, however, the truth about environmental degradation in the Eastern Bloc became undeniable, and these environmental groups provided the foundation for these regimes to be called out on their lies – not only their environmental lies, but their economic and political lies, too.

And in the end, the debt was paid.

[i] Crowd control specialists agree that when numbers of demonstrators reach a critical point (over 300 000 or 400 000 individuals massed on one avenue or a large square which is what occurred repeatedly in the second half of 1989) it becomes impossible to force the human mass to yield: the demonstrators, even if shot at, do not have the possibility to disperse since they cannot turn around and run given the density of the crowd. It is the same problem as evacuating a stadium under a terrorist threat (as during the Paris attacks in the Stade de France where authorities chose to keep the crowd, including the French President, inside the stadium). Even if the crowd was persuaded to disperse, with such large numbers of demonstrators, the operation would be extremely slow and probably end in a stampede which would slow down the process. The human traffic jam would then leave no other choice for the demonstrators near the armed troops than to charge forward since it would be a choice between being shot in the back or being shot in the chest, the second option having at least a one-in-a-thousand chance of breaking through the line of troops and their tanks and survive. Thus, the only options for the authorities is to either appease the crowd by promising negotiations and reforms or to use force which would then cause the stampedes, the desperate attempts by demonstrators in the front row to attack the riot police and thousands of deaths. In 1989, the Communist authorities chose the first option; in 2011 Bashar Al Assad chose the second option saving the régime at the cost of a country devasted by ten years of civil war, up to a quarter of a million dead and nearly a quarter of the population having fled the country. (Oleg Kobtzeff, personal communication).

|

Bibliography

|

- Kirchhof, Astrid Mignon, and J. R. McNeill, ed. Nature and the Iron Curtain: Environmental Policy and Social Movements in Communist and Capitalist Countries, 1945–1990. U of Pittsburgh P, Pittsburgh: 2019. Print.

- Kobtzeff, Oleg. “Environmental Security in Civil Society”. Central and South-central Europe in Transition, ed. Hall Gardner. Praeger, Westport, Connecticut: 2000. 219-296. Print.

- McDermott, Kevin, and Matthew Stibbe, ed. “The Collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe: Origins, Processes, Outcomes”. The 1989 Revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe: From Communism to Pluralism, Manchester UP, Manchester: 2013. Print.

- Miller, Chris. The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy: Mikhail Gorbachev and the Collapse of the USSR. U of North Carolina P, Chapel Hill: 2016. Print.

- Schreiber, Helmut. “The Threat from Environmental Destruction in Eastern Europe”. Journal of International Affairs, 44.2 (1991): 359-391. Print.

- Stahel, Richard. “Environmental Crisis and Political Revolutions”. Social Transformations and Revolutions: Reflections and Analyses, ed. Johann P. Arnason and Marek Hrubec, Edinburgh UP, Edinburgh: 2016. Print.

- “The Curtain Rises: Eastern Europe, 1989: 10 Years, 10 Months, 10 Weeks and 10 Days”. LA Times, the Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1989. Accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-12-17-ss-1794-story.html. Web.

- Verdery, Katherine. Secrets and Truth: Ethnography in the Archive of Romania’s Secret Police. Central European UP, Budapest: 2014. Print.

AFTERWORD by the editors of N&C - Nature & Cultures

The crucial role played by environmentalist dissidents, the ecological motives that drew entire populations into the streets of Central and Eastern Europe in 1989 causing rapid régime change is now part of our collective amnesia. How could we have forgotten that Ekoglasnost in Bulgaria had been the vanguard of opposition starting the process of régime change in the middle of a major international conference on environmental protection in Sofia? Or that the most important opposition group in Slovakia leading massive demonstrations in Bratislava in 1989 was above all an environmentalist movement? Or that it was aggressions against nature that launched the first demonstrations in Budapest which would eventually attract hundreds of thousands of protestors and bring down the government? At a time when we are being warned of unprecedented planetary environmental upheaval, why are we not debating the lessons of Chernobyl which revealed, first of all, how critical were environmental affairs in global geopolitics and secondly, how such an event can not only destabilize an entire political and social system (as was believed by Georgian president and former Soviet Foreign Affairs Minister Chevarnadze and by the entourage of Mikhail Gorbachev) but even turn a page in international history? And what can explain that powerful environmentalist organizations became almost immediately marginal not years but only months after helping to end several Marxist-Leninist régimes in Europe?

Environmentalist parties exist today in Albania and in all the states that had been a part of the Soviet Union, of all of the Soviet block and of Yugoslavia. But in their present parliamentary assemblies, in the EU Parliament (with the exception of the Baltic States) and even in small assemblies of local government–-municipal or regional–-the number of seats won by green parties is inexistent, or, at best and in rare exceptions, marginal. Not a single one of these green parties is capable of rallying more than 1% or 2% of the electorate.

Possible causes could be the following:

Environmentalist parties exist today in Albania and in all the states that had been a part of the Soviet Union, of all of the Soviet block and of Yugoslavia. But in their present parliamentary assemblies, in the EU Parliament (with the exception of the Baltic States) and even in small assemblies of local government–-municipal or regional–-the number of seats won by green parties is inexistent, or, at best and in rare exceptions, marginal. Not a single one of these green parties is capable of rallying more than 1% or 2% of the electorate.

Possible causes could be the following:

- the diversionary effect of the fall of Communist régimes and their side-effects in the 1990s: radical changes of the economies, of social structures, and in daily life, which drove the masses first to avidly pursue the newly discovered pleasures of consumerism and then, forcing them to adapt and even survive in a new aggressive job market—relegating environmental affairs to the less urgent concerns;

- the special case of the historical status of environmental movements in Yugoslavia, and in its successor States: as noted as early as the 1980s by world renown expert Barbara Jancar-Webster and others, all cells of anti-régime opposition and particularly the earliest groups of environmental dissidents were infiltrated by the secret services and other agents of influence of Belgrade to reroute their ideological debates towards strictly nationalistic agendas—a “divide in order to reign” strategy which, getting out of control, not only explains the wars of succession of the 1990s, or why environmental like any other demands comparable to those of Solidarity in Poland or Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia took a backseat in the inter-ethnic bloodshed of those years, but also why environmentalism in these former territories of Yugoslavia had even more difficulty in maturing than in the other former Communist countries;

- the crucial importance of the geopolitics of fossil fuels which (at least in the short term) makes resolving environmental problems less urgent than resolving such questions as which position to take on the overbearing presence of Russia as a gas exporter, and on the planning of rival pipeline projects intended to pass through or not to pass through one’s national territory;

- the influence of the United States over its new Central and Eastern European allies or of Russia, still exercising strategies of seduction, pressure or coercion in the region; the United States, and the Russian Federation even more, are superpowers that increasingly minimize environmental priorities in global affairs in general, particularly in the context of the above-mentioned geopolitical intrigues involving oil and gas;

- the new interests of powerful international and local investors promoting such ecologically destructive activities as fracking, industrial agrobusiness and other ventures;

- privatization and corruption which confiscates public lands for the use of destructive real estate developers or other entrepreneurs with only predatory attitudes towards nature, the common Heritage or even environmental common sense;

- the rise of populism, a worldwide phenomenon which typically denies global warming and mocks environmentalists as elitists out of touch with the needs of the working class and especially of rural populations (farmers, hunters, fishermen, etc.)