City in a Park, City by the Sea: My Helsinki

text and photos by Oleg Kobtzeff (Except historic documents)

Oleg Kobtzeff is an Associate Professor at the American University of Paris

NOTE: this article was written before the war on Ukraine in February 2022 (which caught the author in his latest visit to Finland). The strong links between the Finnish people, Saint Petersburg and Russia in general studied below have been considerably dammaged. Finland has since joined NATO, which would have been unthinkable as late as 2014.

Oleg Kobtzeff is an Associate Professor at the American University of Paris

NOTE: this article was written before the war on Ukraine in February 2022 (which caught the author in his latest visit to Finland). The strong links between the Finnish people, Saint Petersburg and Russia in general studied below have been considerably dammaged. Finland has since joined NATO, which would have been unthinkable as late as 2014.

Any content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.

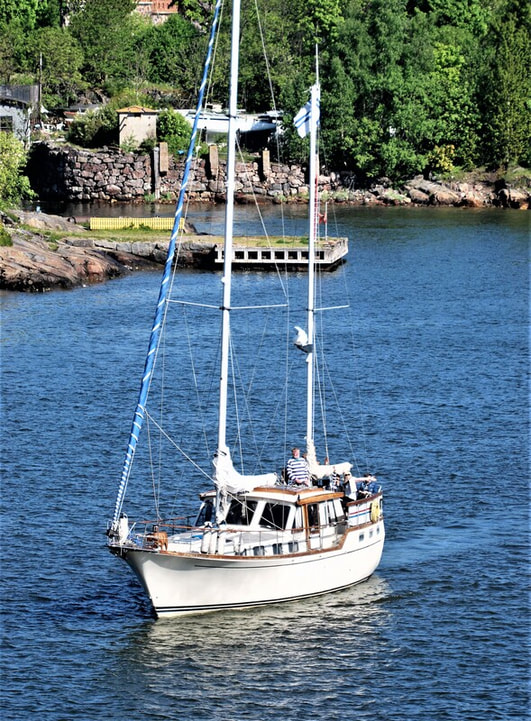

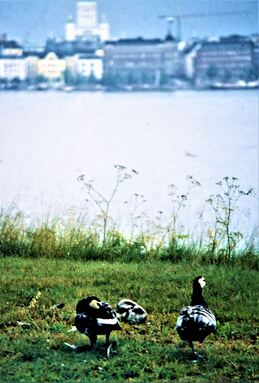

It is extremely difficult to walk or ride through downtown Helsinki without passing through lush wooded areas or along the Gulf of Finland. It is striking how any map of Finland’s capital reveals that more than a third, if not half, of the space is dedicated to nature. Gallery above - left and middle: countless footpaths in the city center and its periphery often lead fishing enthusiasts or hikers, whether on a summer day or in minus 35°C weather, to the early 20th century bridge leading to Seurassari, an island and an open-air museum of historic rural architecture. Gallery above - right: farmers and merchants from countryside communities bring their boat through Finland's numerous waterways and dock in theHelsinki's harbor which is in the very heart of the city. There, their vessel becomes a floating stand at the weekly produce market. Below right: the coast of Finland's capital is not an artificial park but a genuine wilderness; its scores of bird populations have been the delight of generations of Helsinkites on their outings, for many, just outside of their homes.

elsinki is more a park than a city.

Central Park shapes the identity of Manhattan, just like Villa Alba, Villa Torlonia, and Villa Doria Pamphili shape the identity of Rome. What would London be without Hyde Park or Paris without Parc Monceau, Parc Montsouris and the Buttes Chaumont. But no matter how beautiful, no matter how grandiose, all these gardens as well as many others in the world, while covering an important portion of a city’s square mileage, are all parks located in cities. Helsinki looks more like a city located in a park.

Central Park shapes the identity of Manhattan, just like Villa Alba, Villa Torlonia, and Villa Doria Pamphili shape the identity of Rome. What would London be without Hyde Park or Paris without Parc Monceau, Parc Montsouris and the Buttes Chaumont. But no matter how beautiful, no matter how grandiose, all these gardens as well as many others in the world, while covering an important portion of a city’s square mileage, are all parks located in cities. Helsinki looks more like a city located in a park.

|

Am I exaggerating? Actually, it is extremely difficult to walk or ride through downtown Helsinki without seeing lush wooded areas or the Baltic Sea. To remember the exact names and locations of the monuments and the streets I enjoy roaming, I unfold a large map of Finland’s capital. What strikes me about it, is the size and proportion of zones colored in green and which the cartographer also represented with small drawings of trees. It seems that more than a third, if not half, of the map is dedicated to nature. And then what strikes me is how Helsinki seems small, although 654,848 inhabitants live within its city limits by the latest count (in 2020), which, makes it a relatively large city by North American standards, larger than Baltimore or Milwaukee. In addition, nearly one million inhabitants populate the suburbs. So, the modest size is an illusion. What creates this illusion is how the city has been planned: urban structures scattered between tracts of woodlands and the bays and coves of the Gulf of Finland.

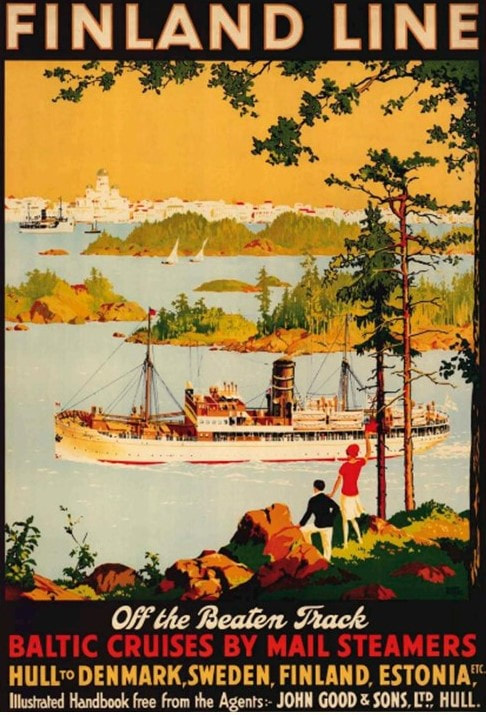

A first time visit to Helsinki is the contrary of a cultural shock. The city reveals itself so discreetly that you barely notice that you have arrived. A passenger on a boat will notice a few buildings hidden behind the dark rows of spruces, birches, aspen and other coniferous and deciduous trees standing on a tormented coastline made of grey granite boulders. If you arrive by plane, and if on a rare occasion the cloud cover is minimal (yes, it rains a lot!), your window will only reveal an endless wilderness. During the ride from the airport, or if you arrive by suburban train or bus, you will stay emerged in a sea of evergreens, aspens and birches, wondering when you will finally reach the outskirts of the city, but before you know it, just as you start getting curious about those charming late 19th-century townhouses and that Soviet-looking large square gray building with columns, you'll be surprised to discover that you have arrived downtown. The big grey official building is the Parliament which would look as arrogant as its Stalinist counterparts in the ex-Soviet Union if it was not humbled by its surroundings of trees, lawns and a small lake nearby. |

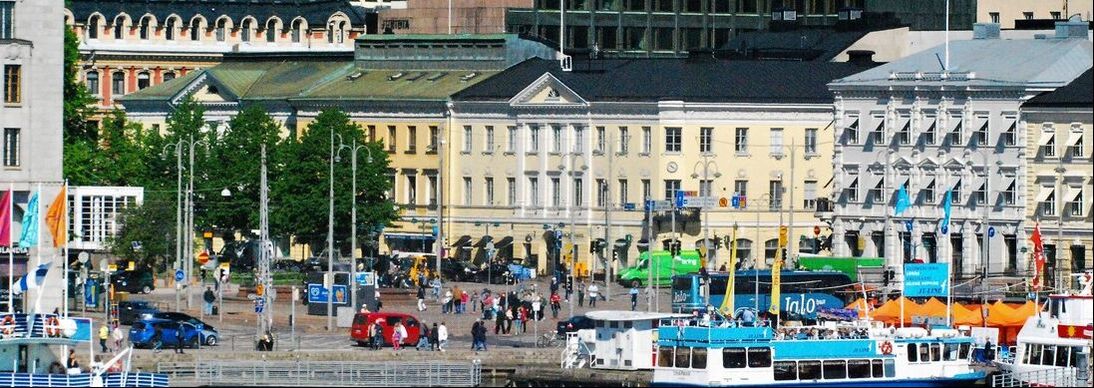

Above: Besides the forests and parks with which the Helsinki's urban environment is completely intertwined, all of its southern city limits are bordered by the Gulf of Finland. From the days in the 18th century when Helsinki was only a small fishing community, to the present where military naval activity, shipbuilding, maritime commerce, sports and tourism make it one of the busiest seaports of Europe, the Baltic Sea has always shaped the life of Finland's capital. Left: a private yacht, on its way out into the Gulf of Finland, passes the fort of Suomenlinna built in the period of Swedish rule. Right: the Astoria, the world's oldest cruise ship (formerly the Stockholm which had rammed and sunk the Andrea Doria in the most famous maritime accident of the mid-20th century), spends only a few hours in Helsinki's passenger harbor as other cruise ships (now, usually much larger) come and go to and from the very center of the city, only a few yards away from the office of Finland's president, other government buildings and one of the major squares. The daily ballet of cruise ships and ferry-boats still seem to be more than routine for these interested young locals admiring the vessels from one of the piers.

If Disneyland’s central avenue had not been “Main Street USA” but “Main Street Finland”, the avenue with a park in the middle––Pohjoiesplanadi (the Northern side) or Eteläsplanadi––would be it. Not the longest street of the capital, but its most opulent, it is the equivalent of the Champs Elysées, or rather Via Veneto (for the greenery and its short extent), reinvented by a talented provincial architect helped by a movie set designer and a German toy maker specializing in those little buildings that decorate the railways of electric train enthusiasts. Pohjoiesplanadi-Eteläsplanadi is the heart of Helsinki because of its strategic location: it leads to the great market square, the harbor, which is right in the middle of the city, where the main government buildings are also aligned and because it is a synthesis of what the city is all about. From the architectural point of view, it is almost a replica of Saint Petersburg’s Nevsky Avenue, yet slightly more Parisian, slightly more classical Northern European (Dutch, English, Scandinavian or Russian) with some houses made of local granite, quite a few painted in yellow, others painted in pastel colors, many with white porticos, slightly more art deco and art nouveau; there are a few inevitable glass and steel buildings of the 1960s or 1970s but not too many.

|

Above: Helsinkites enjoy a sunny morning in late June around one of their favorite spots, the Havis Amanda fountain on Market Square in Kaartinkaupunki near the city's town hall. Havis Amanda, the statue of a mermaid at the center of the fountain (not seen on the picture) modelled in 1906 in Paris by the sculptor Ville Vallgren (1855–1940). The basin surrounding the centerpiece receives its water from the mouths of the four by sea lions, two of which appear here. Most of the time, the sea lions are far more interesting to the children (as well as to this photographer) than the mermaid itself.

|

What is the name of the inhabitants of Helsinki? |

A strange resemblance to Saint Petersburg

|

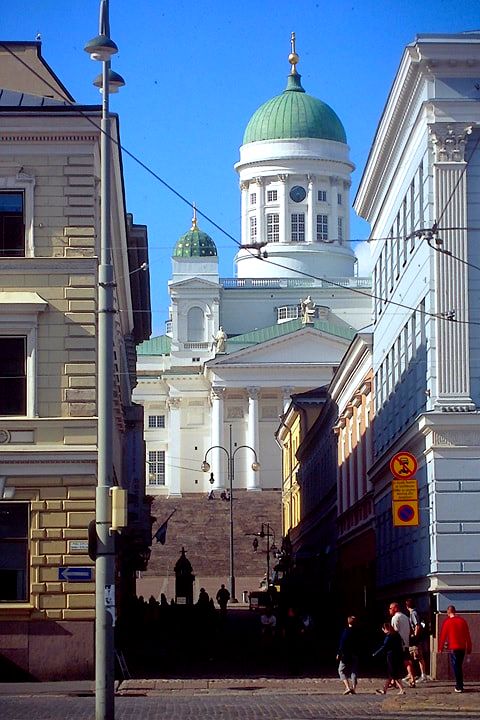

The great avenues of Helsinki, like the corner of Pohjoiesplanadi and the central market square (above), resemble the main architectural style of Russia's Saint Petersburg because of the political and artistic links between the two cities (separated only by a few hours by train) throughout the 19th century. The Orthodox Dormition cathedral, inaugurated in 1868 on the highest point of the center of Helsinki, breaks with the neo-classical style, forever forcing its neo-Russian medieval revival style on the skyline of the capital of Finland, deliberately marking Russian domination.

|

The Russian flavor on this avenue, like almost everywhere in the historic center, is very powerful.

It is not Sleeping Beauty’s castle that stands at the end of the avenue, but a tall church made of bricks, surmounted by a large cone-shaped cupola and a belfry, and topped with fourteen little onion-shaped domes. It is the Orthodox cathedral of the Dormition. Not far from it stands Saint Nicholas Lutheran cathedral, a majestic white neo-classic square shaped monument with a Corinthian portico on each side. It is surmounted by a dome which is much smaller than similar buildings like Saint Isaac cathedral in Saint Petersburg or Washington’s Capitol. The smaller proportions of that dome reduces the church to a more human scale, although people look very small when seen standing next to the colonnades. The cathedral which is an icon of Helsinki appearing on all tourist brochures and travel media, stands on a hill overlooking Senate Square which is almost entirely surrounded by rectangular four or five-story buildings painted yellow with white pilasters or colonnades. The resemblance with Russia’s old imperial capital Saint Petersburg is striking. It is due to the architectural styles that identify Helsinki. |

First of all, early to mid-nineteenth century neo-classical architects—often the same who designed the buildings of Saint Petersburg– were those who turned the sleeping fishing town into the fourth capital of the Russian Empire: Helsingfors (its Swedish name), capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland. These architects and urban designers most strongly fashioned Helsinki (its native Finnish name) as witnessed by the many large official buildings inspired by the most sober Greek-Roman monuments or Palladio and, as mentioned earlier, the usually yellow or otherwise pastel color of their walls and white columns, pilasters and trimmings.

Then, as in many cities of Central and Eastern Europe, but particularly in those along the Baltic coast, Art Nouveau becomes very popular in Helsinki, particularly in one of its avatars which is the National Romantic style of Nordic countries, also typical of Saint Petersburg. This National Romantic style is radically different from that other nostalgic style which was Gothic Revival style. The National Romantic style typified by many individual houses, apartment buildings and Helsinki monuments such as the train station, the National Theater, the Kallio church and especially the National Museum recycled ancient, almost primitive, simple massive forms This is why during the Cold War, when Western filmmakers were not allowed to shoot in the USSR if its authorities were not guaranteed control over the script, Helsinki stood in for Leningrad or even Moscow in political thrillers like The Kremlin Letter, Gorky Park or White Nights. Many of the monumental features––museums, Belle Epoque department stores and retail buildings, statues and churches, cafés and ––that characterize downtown Saint Petersburg are typical of a 19th century provincial city of the Russian Empire whether Petrozavdsk in Karelia or Odessa in Ukraine. The Germanic, Flemish or Scandinavian elements of architecture do not contradict that Russian atmosphere since they were also part of imperial Russia’s urban landscape. The resemblance between Saint Petersburg and Helsinki is far from being coincidental.

|

|

|

The architectural resemblance explains why in several international political thrillers, Helsinki stood in for Leningrad as in "White Nights" (left, with Saint Petersburg native, dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov) or even Moscow in "Gorky Park" (right).

Helsinki had been not only a city of the Russian Empire, since Finland was conquered from Sweden in 1809, but it also became one of the four official capitals of the Empire, the fourth after Saint Petersburg, Moscow and Kiev. It is during that Russian period that Helsinki grew into an important urban center. Throughout the 18th century, the town founded by the Swedes in 1550 as the port of Helsingfors was not an important city but was rather a large fishing village living a quiet life in the shadow of the imposing Swedish archipelago-fortress of Sveaborg (Suomenlinna as Finns renamed it) which still stands less than a nautical mile away from the continent. When during the Napoleonic wars the troops of tsar Alexander I conquered Finland from Sweden, the province became an autonomous Grand Duchy with its own system of government including a national currency, a postal system and even a legislative assembly––the Lantdagar (its Swedish name) or Suomen maapäivät (in Finnish). In 1812, Alexander I ordered the move of the Lantdagar from Porvoo to Helsingfors, which the Finns called Helsinki and the Russians continued to call “Gelsingfors”until 1917, and which became the capital of the Grand Duchy. Extensive construction began in that first quarter of the 19th century, since the city had been greatly damaged by a fire in 1808. After Turku also suffered a great fire, in 1827, the only Finnish University of the time––the Royal Academy of Turku––was also moved to the new capital and remains there, to this day, as the University of Helsinki. Its oldest building is one of the typical yellow buildings with a white portico on Senate Square. Carl Ludvig Engel and later Johan Albrecht Ehrenström had both worked on the urban landscape of Saint Petersburg which bears much of the influence of the neo-classic style they represent, when they were put in charge of an ambitious plan to transform the partially ruined provincial Finnish seaport into an imperial capital.

Below: The Government Palace, presently the Office of the Prime Minister on the East side of Senate Square (yellow building). Carl Ludvig Engel, or Johann Carl Ludwig Engel (3 July 1778 – 14 May 1840), was a German architect most noted work can be found in Helsinki, which he helped rebuild. His works include most of the buildings around the capital's monumental centre, the Senate Square and the buildings surrounding it.

Above: the Finnish National Theatre (Finnish: Suomen Kansallisteatteri), established in 1872, The building hosting the Finnish National Theatre today was completed in 1902 and designed by architect Onni Tarjanne in the National Romantic style, inspired by romantic nationalism. This style influenced many apartment buildings of the early 1900s in the historic center (below,, middle). That style has also influenced Saint Petersburg architects (who in the very cosmopolitan Russian metropolis were of various origins from Baltic regions) and only enriches the resemblance between the capitals of the Gulf of Finland. The National Museum of Finland (bottom), a very rich historic and ethnographic museum built between 1905 and 1910 by the Gesellius, Lindgren, Saarinen architectual firm is another example of the National Romantic Style.

The atmosphere of classicism or art déco and art nouveau––also typical of the capital–– changes as you leave the center and approach the suburbs. Vantaa, Espoo, and Kauniainen, the municipalities surrounding Helsinki, are made essentially of large modern wooden houses, plus a few older ones, that are one or two stories high and surrounded by vast gardens. Their neighborhoods would remind you of New York’s Scarsdale, Boston’s Cambridge or Ottawa’s outskirts if you were not literally in a wilderness. Here, the Scandinavian Peninsula’s taiga that starts growing beyond the Arctic circle, where the tundra begins to be replaced by trees, spreads all the way South, towards the Baltic where it has evolved into a sub-arctic rain forest difficult to penetrate so thick is the vegetation. That is why Finland’s tormented coastline with its black rock formations constantly reminds you of the islands off America’s Northwestern coast. If you have lived there, the coastal zones of the Greater Helsinki will make you feel at home. You will only be slightly disoriented by the absence of mountains, but as you wonder where they have disappeared, you may catch yourself thinking that the trees are so high that you cannot see them. And then you will remember that Finland’s rare mountains are located far away in Lapland and are quite small. Meanwhile, you will be distracted by the wildlife.

A city where wildlife is at home.

|

Whales do not live in the Baltic, but their absence is largely compensated by a profusion of many other wild animals typical of the Great North, not only in the suburbs but sometimes in downtown Helsinki itself. Like all self-respecting dwellers of Canadian, Russian and Scandinavian cities wanting to appear “civilized” and prevent any prejudiced tourist to spread clichés about their Nordic environment, natives of Helsinki may insist that no polar bears roam their streets. But anyone who has become familiar enough with that city can be nevertheless tempted to add a “however”…

When walking along the shores of the Baltic in the alleyways of the Kaivopuisto Park located only minutes away from Parliament square and the heart of the capital, it is not bears but birds that make it an environment which is hostile to humans. Or at least do they try to maintain such unwelcoming appearances by deploying their wings, sticking out |

their black necks towards pedestrians, pointing their white heads and pink tongues and hissing with such righteous indignation that you hesitate to advance any further, you feel vaguely guilty and start looking around for “no trespassing ” signs that you feel you must have missed. A few steps further and another goose expresses itself with the same outrage. The scene repeats itself every few yards all along the seaside as if you have committed an act of unspeakable infamy against all of Creation and particularly parenting geese.

The authorities are obviously on the side of the birds and all other creatures. I found out that private homeowners cannot just organize their gardens as they please. Wild animals’ rights prevail over humans’ property rights. Dogs for example are not allowed to run unattended in your own private garden and are basically expected to stay indoors [TW1] except for walks on leashes. I found this out when I was invited for dinner by Irina, a writer living just on the outskirts of Helsinki. Dropped blindfolded in the middle of this forest without being told to which continent or to which country you have been brought, it would be very difficult to realize you are just outside of a large European city and not at some remote trade post in the Yukon Territory or Siberia. “Dogs are considered a danger for the wildlife”, explains my hostess, as I pet the friendly family pooch in the kitchen, “for several years, the law has been protecting the wild animals who visit our yards. Now we see more pheasants, quails or partridges just outside of our windows and it is a pleasant sight”. Even safer from canine jaws are birds of prey like ospreys, hawks, falcons and especially owls that can be easily spotted in the summer since these children of the night cannot enjoy the cover of full darkness in a land of the midnight sun. It would be impossible to mention all the other land and maritime feathered life forms native to the area. My old beloved guidebook Let’s Explore Nature in Helsinki by Matti Nieminen and Eero Haappanen provides a list of birds that can be observed in Helsinki and its suburbs. It covers all of pages 167 to 170, continues on one third of page 171 and is printed with such small fonts that you need a magnifying glass. That’s a lot of birds.

The authorities are obviously on the side of the birds and all other creatures. I found out that private homeowners cannot just organize their gardens as they please. Wild animals’ rights prevail over humans’ property rights. Dogs for example are not allowed to run unattended in your own private garden and are basically expected to stay indoors [TW1] except for walks on leashes. I found this out when I was invited for dinner by Irina, a writer living just on the outskirts of Helsinki. Dropped blindfolded in the middle of this forest without being told to which continent or to which country you have been brought, it would be very difficult to realize you are just outside of a large European city and not at some remote trade post in the Yukon Territory or Siberia. “Dogs are considered a danger for the wildlife”, explains my hostess, as I pet the friendly family pooch in the kitchen, “for several years, the law has been protecting the wild animals who visit our yards. Now we see more pheasants, quails or partridges just outside of our windows and it is a pleasant sight”. Even safer from canine jaws are birds of prey like ospreys, hawks, falcons and especially owls that can be easily spotted in the summer since these children of the night cannot enjoy the cover of full darkness in a land of the midnight sun. It would be impossible to mention all the other land and maritime feathered life forms native to the area. My old beloved guidebook Let’s Explore Nature in Helsinki by Matti Nieminen and Eero Haappanen provides a list of birds that can be observed in Helsinki and its suburbs. It covers all of pages 167 to 170, continues on one third of page 171 and is printed with such small fonts that you need a magnifying glass. That’s a lot of birds.

|

Very large hares with gray fur and a white belly, with a strange moose-like nose are common to Helsinki, even as far as downtown, not to mention the squirrels––not the grey American kind that has invaded England, but the smaller ones with fluffier fur of a flamboyant red color. They run around everywhere and you will find them rummaging in your pockets or your bags if you are so imprudent as to let your coat or camera case on the ground for more than thirty seconds. Much less visible, but still observable on occasion, foxes, weasels, martens, badgers, otters, deer and, my favorite but more rare, grey seals, appear to hikers who know how to walk discreetly on the numerous hiking trails that criss-cross the city and its suburbs.

One of the scores of squirrels in the Seurassari open-air architectural museum. The abundance of wildlife population is difficult to compare to any large city in the world.

|

A hiker's paradise

|

As shown in the early 20th century poster and in this view taken from the SPOT satellite, Helsinki's green spaces offer an amazing network of trails that allow to follow the Baltic seashore or to walk further inside the forests of the Greater Helsinki from all the way downtown to several dozen kilometers beyond city limits without ever having to cross a road.

|

So, polar bears do not roam the streets of Helsinki. But as mentioned earlier, the "however" is fully justified. This is most certainly thanks to the commitment of municipal and national governments to environmentally friendly policies, a reflection not only of Finland's political culture but of the population’s mentality as well––a mentality characterized by self-discipline without the self-righteous lecturing that locals manifest towards undisciplined tourists in a certain alpine nation that will remain anonymous. In my first week in Helsinki, many years ago, I discovered an idyllic opportunity for the kind of fanatical hiker that I am: you can actually hike on several trails, following the Baltic seashore or walking further inside the forests of the Greater Helsinki from all the way downtown to several dozen kilometers beyond city limits without ever having to cross a road… or almost. In the middle of nowhere, on a Sunday, with no signs of cars for many minutes, I had to cross a highway in the Western reaches of Espoo. A woman, the only living creature that I had encountered for miles, diligently stopped at the red light forbidding us to cross. I looked left and looked right, and couldn’t spot the slightest trace of a car from horizon to horizon. I thought “I am completely safe and the nearest policeman is dozens of miles away, probably sleeping off the effects of a Saturday night party”, and I jaywalked. I noticed that the woman stood still, diligently waiting for the light to turn green. I was the only witness, and we were as lonely as if we were on Mars. However, the lady waited patiently. She graced me with a smile full of indulgence towards my unruly behavior. In the little Alpine country mentioned earlier I would have heard a lecture in an aggressive tone on how the law is the law and applies to foreigners as well, especially ill-mannered bums like me. I would learn, as I got to know Finns, that the mixture of self-discipline towards oneself and tolerance towards others is a trait of character that makes it so pleasant to live in their country. Noticing this tolerance towards foreigners gave me insight on how Finns manage to perceive their own identity which is marked by powerful cultural influences of domineering foreign powers.

In the shadow of Russia.

Above: besides the Orthodox churches numerous traces of Helsinki's and Finland's past under Russian rule mark the capital's landscape. One of the most obvious is the double-headed eagle on top of "Tsarina's Stone" a rose granit obelisk standing on Market Square, erected in commemoration of the Russian Imperial couple's visit to Helsinki in 1833.. Crowds of sunbathers on the lawn on Market Square can be seen reflected in the giant gold-leafed ball.

I did not take polls during my visits to their city but I nevertheless couldn’t but notice the number of inhabitants of Helsinki who embraced their Russian experience as a heritage to be proud of and not only as a trauma.

Finland suffered less than Poland in its relations to Russia or the USSR, but the tens of thousands of Karelians fleeing their beloved homeland during the advance of the Soviet troops in 1940, and again in 1944, is a terrible witness to the desolation the Red Army inflicted upon the land and its inhabitants. The witnesses have not been forgotten. With more than half of a million refugees––more than 13% of the country’s entire population––such a trauma can only remain in collective memory.

Surprisingly, the damage to Russia’s image in Finland seems to be less than what I witnessed in other countries that had been subjected to Russian rule. I was always very open about my interest in Russo-Baltic relations which have as much to do with my roots on both sides of Russia’s Northwestern borders as with my academic research on Russia’s influence on its neighboring countries. In several parts of the world, bringing up this issue of Russian influence I sometimes felt that I was walking on eggs, as if I was an intruder, stirring up questions preferably forgotten. This was particularly true among indigenous Alaskans and especially Ukrainians for whom the subject was explosive even decades before the annexation of Crimea. In Helsinki, I never felt the slightest discomfort. On the contrary.

Finland suffered less than Poland in its relations to Russia or the USSR, but the tens of thousands of Karelians fleeing their beloved homeland during the advance of the Soviet troops in 1940, and again in 1944, is a terrible witness to the desolation the Red Army inflicted upon the land and its inhabitants. The witnesses have not been forgotten. With more than half of a million refugees––more than 13% of the country’s entire population––such a trauma can only remain in collective memory.

Surprisingly, the damage to Russia’s image in Finland seems to be less than what I witnessed in other countries that had been subjected to Russian rule. I was always very open about my interest in Russo-Baltic relations which have as much to do with my roots on both sides of Russia’s Northwestern borders as with my academic research on Russia’s influence on its neighboring countries. In several parts of the world, bringing up this issue of Russian influence I sometimes felt that I was walking on eggs, as if I was an intruder, stirring up questions preferably forgotten. This was particularly true among indigenous Alaskans and especially Ukrainians for whom the subject was explosive even decades before the annexation of Crimea. In Helsinki, I never felt the slightest discomfort. On the contrary.

The monument to Alexander II (above), continues to be decorated with flowers, sometimes spontaneously by locals. A strange symbol of Finnish national pride it is a great paradox. Erected in 1894 to commemorate the "the tzar liberator's" re-establishment of the Parliament of Finland in 1863 as well as his reforms that increased Finland's autonomy from Russia, his statue became a symbol of national pride a few years later when the policies of russification of Nicolas II as well as plans to reduce the autonomy of Finland (which had home rule, a currency and a postal service of its own) began to considerably threaten the Finns who had just began to find strong narratives to define their national identity. Fearful of the consequences of open demonstrations Finnish patriots began venerating the statue to Alexander II whose policies to Finland were commemorated as an unspoken criticism of his grandson's attempts to reverse them. The Russian authorities could not forbid the people of Finland to venerate a tzar and therefore, this tongue-in-cheek form of passive resistance took root as a form of Finnish patriotic activism. It is also paradoxical that Alexander II is seen as a positive figure by Finns, whereas just across the Baltic Sea, on the Southern shore, Poles remember him as the one who, also in 1863, crushed their uprising which ended in a bloodbath.

The head librarian of the Slavic department of Helsinki University’s Library on Senate Square made me feel at home. A refugee from the Finnish lands still under Russian rule, she greeted me with kindness and an enthusiasm that I had never met anywhere in my decades of travels and bookworm activities; she spontaneously addressed me immediately in Russian rather than in English (my knowledge of Finnish being catastrophic), made amazing efforts to help me with my research and introduced me to a few scholars and to other Finns with Russian ties thanks to whom I was even able to enjoy a little social life when I came to visit Helsinki for work or for pleasure.

|

In the same library, one act of generosity made me proud of my work and my roots. After it moved from Turku to the imperial capital of Helsinki, the Grand Duchy’s main library was granted a special privilege as one of the four state repositories of every exemplary of printed material. One copy of any item coming off the press in any part of the Empire was sent to each of the four imperial repositories. The Helsinki Yliopiston Kirjasto now holds one of the four richestcollections of books in Russian, and in the other languages of the Russian Empire, printed before 1918. Much had to be surrendered to the Soviet authorities (along with lands in the East and other war tributes) at the end of World War II, but the richness of what remains is astonishing. Why some scholars studying Russia prefer this Helsinki library to those in Russia is not only the relaxed atmosphere and the absence of bureaucratic hassle needed to access most important Russian collections: the Slavic department of Helsinki University’s library offers patrons free access to the shelves where the publications are stacked, including most early 19th century bibliographic treasures and other rarities. As in most research libraries specializing in rare books, a researcher can browse at will through all the monographs and periodicals without having to order only a few titles at a time from the reserves, and wait for twenty minutes to realize that there is nothing of interest in the four or five books brought to you by a library assistant. But here, a researcher can accomplish in one week what should normally take a month. Eventually, I found a series of documents that were so rare (although printed recently) that the assistance of an official became imperative. These were fac simile reproductions of large format 17th century Swedish maps indicating dozens of small settlements along the Neva river, where now stand Saint Petersburg and its suburbs––ancient communities of Russians, Swedes, Ingrians and Karelians coexisting side by side, before the founding of Peter the Great’s new capital in 1703, and completely ignored by historians.[1] At this point of my research I needed assistance from the library personnel to print large size reproductions of those documents so that I could take them home and study them at leisure (a task I keep returning to, years later). The job was a delicate one requiring hours of careful work in the photographic lab of the reproductions department of the library that, understandably, required me to fund the cost. It was going to be a considerable investment. I also had to explain the relevance of such an enterprise (always a risk to the integrity of the originals) to the head of the reproductions department, a quiet, even placid, yet methodical blond young man with glasses and a goatee, who called me back a few days later to pick up the reproductions. The result––the quality of the photocopies––was a tribute to the professionalism of the young man and of his staff. But now was the time to pick up the tab. I had calculated that this would cost me several hundred Euros. When I asked for the verdict, the department head answered me in a cool, slightly hesitant unemotional tone.

“Well… you see, we considered your project and thought it was interesting and useful research. Also, what you are studying is part of our own history, so… we decided that we would not charge you.” |

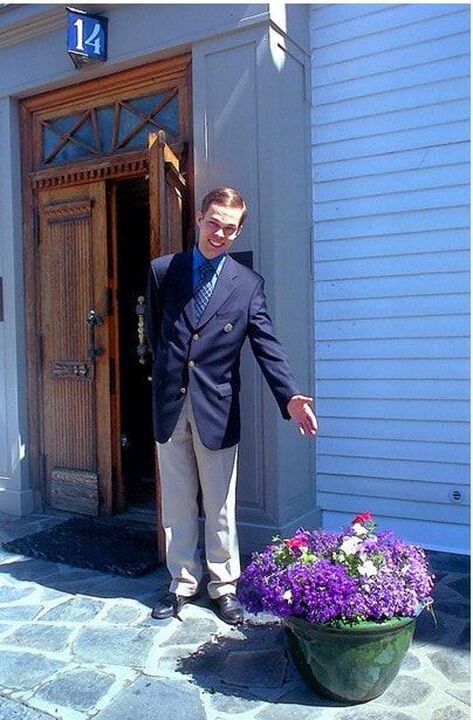

The Assistant curator of the Mannerheim Museum, points out

to me that the colors of the flowers at the entrance coincide (with a degree of imagination) to the white, blue and red of the Russian flag. What the young man and the director of the museum did accurately explain to me was how Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, independent Finland's founding father, never forgot his years in the former Russian Empire where he rose to the rank of general, and maintained a strong sentimental attachment to Russia. [1] The results of that particular research project appeared a few months later in Kobtzeff, Oleg, "Espaces et cultures du Bassin de la Neva : représentations mythiques et réalités géopolitiques", in Walter Zidaric, ed., Saint-Petersbourg : 1703-2003, Actes du Colloque international, Université de Nantes, mai 2003, Nantes: Centre de Recherches sur les Identités Nationales et l’Interculturalité, 2004, pp. 19-49. |

The Finnish character and identity as seen among the dwellers of Helsinki

|

Such apparent lack of emotion is only a form of modesty; superficial foreign observers, too often, mistake it for coldness. They do not notice the great or small acts of kindness that repeatedly occur every day, in a very discreet way. It might be an employee behind a help desk at the Helsinki train station who just closed her booth, is on her way home after a long day of work, then notices you reading a poster with train schedules and turns back to help you with your trip. It might be a shop keeper who will get out of his or her way to find the rare object outrageously complicated to locate like a pair of galoshes in the summer (no one anywhere ever buys or sells galoshes anymore, even in the winter) or like a very rare and expensive book, which, when it finally gets to Helsinki via the Swedish border then Lapland, you suddenly realize you can no longer afford, but can buy after all because the antique book seller will offer you a never-in-this lifetime discount, and with a smile. Or it could be anyone in the street spontaneously volunteering to give you directions, without trying to convince you to buy typical local pottery or carpets from his cousin’s souvenir shop or trying to flirt with you.

The reserve that seems to characterize so many Helsinkiläinen as well as most of the people of Finland is not only a behavior found among other Northern Europeans. Finns are not Indo-Europeans like their Scandinavian or Slavic neighbors. When you learn how Finns are ethnically and linguistically close to the Saami, the indigenous reindeer herders of Lapland, you uncover a dimension of their origins that few realize. You then become aware of certain particularities. You notice that certain individuals, although blond with blue eyes, also have facial traits that resemble those of Asian people. And then, if you have encountered other Indigenous people elsewhere in the Great North or even in the American West, the reserve, the calmness and the hospitality will remind you of the warmest memories you may have taken away from your hosts in an Aleut fishing village or a Saami .

Natives of Karelia and Lapland sell their artisanal products on market day on Market Square reconnecting Finland's urban dwellers with the Indigenous populations that speak a Finno-Ougric language very close to theirs.

|

These traits combined to Helsinki’s cosmopolitanism explains a lot about how foreigners could be made to feel at home in Helsinki, even the former conquerors from Russia (who rarely appreciate it---unfortunately, some Russians, not unlike some Americans, love complaining about how “they all hate us!”, which is probably a twisted way of feeling important––“better be feared than loved” as Machiavelli puts it). Yes, there probably exists a relatively significant number of Finns in Helsinki and elsewhere who do not like Russians, while others are fearful of immigrants, or simply racist. But cosmopolitanism seems to be part of the identity of Helsinki which appears, recently, to be populated by more and more immigrants from many parts of the world, particularly from the former USSR (the law facilitates obtaining Finnish citizenship for immigrants of Finnish ethnicity like Estonians or Karelians).

My friend Vera von Fersen, the former head of the Mannerheim Museum, who was born in an aristocratic family with an international history and a transcontinental network of ties to––among others–– Sweden, Finland, Russia, France and even young America naturally switches from French, Finnish, Swedish, English or Russian to any of these same languages when socializing with a diversity of friends. For her, it is a natural attitude instilled by a century-old aristocratic education that, since the Enlightenment, was one of the first motors of cultural globalization.

For other Helsinkiläinen, it is a completely different political culture that encourages cosmopolitanism. Socialism has a great influence in Helsinki, in all of Finland and in the Baltic region. Let's remember first of all that the same Socialist and Marxist revolution that reshaped Russia in 1917 also shaked the foundations of Finland which had barely become independent from the same empire. One hundred years after the independence of Finland, the Social Democratic Party of Finland (the SDP - Suomen Sosialidemokraattinen Puolue, or Finlands Socialdemokratiska Parti in Swedish) is still one of the four major political parties in Finland. Its foundation goes back as far as 1899. In the legislative elections of 1916, with 47% of the votes, it, gained a majority in Parliament that will never be repeated in Finland’s history. During the civil war of 1918, the Socialists of the SDP sided with Finland’s Communists (despite the latter’s recent split from the former’s party). Although Communists and Socialists would become more and more opposed on fundamental political questions during the following decades, their common Socialist tradition laid part of the foundations of Finland’s and especially Helsinki’s political culture. While the Communists followed the call for “proletarians of all countries” to unite, particularly with their brothers from the Soviet Union, the SDP turned West and became a major force in bringing Finland into the European Union (in 1995), without, nonetheless, having manifested open hostility towards the USSR or its powerful Russian component. But whether it was inspired by Marxist internationalism or Kantian liberal trans-nationalism, cosmopolitanism was the common denominator of both Socialistic factions that profoundly shaped the mentalities of the inhabitants of Finland and of its capital.

For other Helsinkiläinen, it is a completely different political culture that encourages cosmopolitanism. Socialism has a great influence in Helsinki, in all of Finland and in the Baltic region. Let's remember first of all that the same Socialist and Marxist revolution that reshaped Russia in 1917 also shaked the foundations of Finland which had barely become independent from the same empire. One hundred years after the independence of Finland, the Social Democratic Party of Finland (the SDP - Suomen Sosialidemokraattinen Puolue, or Finlands Socialdemokratiska Parti in Swedish) is still one of the four major political parties in Finland. Its foundation goes back as far as 1899. In the legislative elections of 1916, with 47% of the votes, it, gained a majority in Parliament that will never be repeated in Finland’s history. During the civil war of 1918, the Socialists of the SDP sided with Finland’s Communists (despite the latter’s recent split from the former’s party). Although Communists and Socialists would become more and more opposed on fundamental political questions during the following decades, their common Socialist tradition laid part of the foundations of Finland’s and especially Helsinki’s political culture. While the Communists followed the call for “proletarians of all countries” to unite, particularly with their brothers from the Soviet Union, the SDP turned West and became a major force in bringing Finland into the European Union (in 1995), without, nonetheless, having manifested open hostility towards the USSR or its powerful Russian component. But whether it was inspired by Marxist internationalism or Kantian liberal trans-nationalism, cosmopolitanism was the common denominator of both Socialistic factions that profoundly shaped the mentalities of the inhabitants of Finland and of its capital.

The Socialist tradition also explains the principles of solidarity and social liberalism that appears to define norms of society in Finland and in its capital. With Sweden and the other Scandinavian countries, Finland is to this day and despite neo-liberal reforms in the 1990s ("libertarian reforms" in American vocabulary) one of the most notorious and committed welfare states in the world.According to the new methods of calculating its human development index which now takes into account whether there is more or less inequality in a country, the United Nations considers Finland as the eleventh most developed country in the world after all the Scandinavian countries, Germany, Switzerland, Canada and Ireland and well ahead of the UK (16th), France (18th) or Japan (20th). In other words, Finland is considered as one of the safest countries in the world in terms of protection of the sick, the elderly, the unemployed, the disabled and victims of other “accidents of life” with one of the eleven most egalitarian and wealthiest populations in terms of public services, medical facilities, educational opportunities and other social assets. It is obvious in Helsinki.

|

“I am sorry but our bus will have to take us through a poor and neglected zone”, warned Irina, when we rode together towards her home in the suburbs and that dinner that I mentioned earlier.

“The way the entire city looks, I didn’t think that you had slums in Helsinki”, I replied. “Oh, but you will see, not everything is so perfect here. You have seen only the nice downtown neighborhoods.” After quite a long tour of Helsinki’s outskirts, our bus drove through what seemed to be a rather old quarter. An alignment of four-story gabled wooden houses evoked images of some picturesque fishing towns which hadn’t changed much since the mid nineteenth century––Bergen in Norway, or an old American seaport. To attract tourists, these houses only needed a little paint job, a saloon on the first floor with a nicely decorated doorway, early 1900s lampposts with flowers, and a restored antique fire engine or a carriage with horses parked along the sidewalk. “What is this charming little place?” I asked. “But… this is the poor zone I warned you about.” “Oh… So, these are your slums? And you say that you have been to Paris? You definitely need to see Aubervilliers or Drancy on your next visit so that we could redefine what you mean by ‘poor neighborhood’…”. The Lutheran Cathedral was designed by Carl Ludvig Engel as the climax of his Senate Square layout. Its dome is much smaller than similar buildings like the Saint Isaac cathedral in Saint Petersburg or Washington’s Capitol. Smaller proportions reduce the church to a more human scale, although people look very small when seen standing next to the colonnades.

|

“The Naked time”: the dark side of Helsinki.

All this may sound too much like a fairy-tale account by a retired couple of candy store owners from rural Minnesota who won a free trip to Helsinki. So, it is time, unfortunately, to pause and acknowledge other aspects of the city.

On Friday and Saturday evenings, an eerie transformation turns the quiet, gentle and disciplined inhabitants of Helsinki into... something else. It is like a magic spell cast by a sorcerer in a heroic fantasy novel or the kind of alien epidemic in the Star Trek episode called “The Naked Time”, an outburst of intoxication that drives everyone aboard the starship Enterprise into fits of raving lunacy. I had been warned about this years before I actually witnessed it. I had heard that inhabitants of Leningrad-Saint Petersurg––although not reputable champions of sobriety––feared the landing of cruise ships from nearby Helsinki that would spill crowds of drunken revelers for a weekend on the town. I had trouble believing the horror stories that seemed so exaggerated. After witnessing my first Friday evening in Helsinki, I still have trouble believing what I remember from my first impression. Three middle-aged office employees or executives––two men and one woman––dressed in business suits and carrying briefcases calmly walk down a staircase. The woman suddenly starts laughing hysterically and lets herself collapse in the grass next to the stairs. The two men, stumbling, stop and look at her, giggling, one of them pointing his finger at her as if she had just invented the funniest gag in show business. People sleeping it off in public places. Traces of vomit everywhere. So many people in the streets, staggering, with silly smiles and half closed eyes. A bus driver slowly piloting his vehicle so that he would not hit one of the numerous stumbling drunks constantly surging from everywhere like zombies in a science fiction-horror movie. (Was the driver actually zig-zagging between people passed out on the blacktop in the middle of the main avenues of the city or was this a bad dream I had the next night?)

On Friday and Saturday evenings, an eerie transformation turns the quiet, gentle and disciplined inhabitants of Helsinki into... something else. It is like a magic spell cast by a sorcerer in a heroic fantasy novel or the kind of alien epidemic in the Star Trek episode called “The Naked Time”, an outburst of intoxication that drives everyone aboard the starship Enterprise into fits of raving lunacy. I had been warned about this years before I actually witnessed it. I had heard that inhabitants of Leningrad-Saint Petersurg––although not reputable champions of sobriety––feared the landing of cruise ships from nearby Helsinki that would spill crowds of drunken revelers for a weekend on the town. I had trouble believing the horror stories that seemed so exaggerated. After witnessing my first Friday evening in Helsinki, I still have trouble believing what I remember from my first impression. Three middle-aged office employees or executives––two men and one woman––dressed in business suits and carrying briefcases calmly walk down a staircase. The woman suddenly starts laughing hysterically and lets herself collapse in the grass next to the stairs. The two men, stumbling, stop and look at her, giggling, one of them pointing his finger at her as if she had just invented the funniest gag in show business. People sleeping it off in public places. Traces of vomit everywhere. So many people in the streets, staggering, with silly smiles and half closed eyes. A bus driver slowly piloting his vehicle so that he would not hit one of the numerous stumbling drunks constantly surging from everywhere like zombies in a science fiction-horror movie. (Was the driver actually zig-zagging between people passed out on the blacktop in the middle of the main avenues of the city or was this a bad dream I had the next night?)

Too much self-discipline, too many emotions contained, too much denial of any feelings that may be suspected as signs of resentment or aggressiveness. And the result is too much bottled-in anger or simple frustration that builds up because of the fear of raising any issue that may offend, that may be perceived as conflictual, or arrogant. It is the plague of the North where the solution to living in extremely closed quarters in the winter produces a culture of patience, kindness and tolerance, but at the cost of self-expression. But steam has to be let out once in a while, and that is what, I believe, is the function of these weekly alcoholic carnivals. I have seen it in the years when immersed among Native Alaskans, how past disappointments, unresolved conflicts and traumas are relegated into the deep recesses of repressed memories and suddenly explode at the sight of the first pint of beer in a few days or a few weeks. Otherwise the explosion could occur in the form of an extremely violent verbal confrontation when grown men in tears launch terrible accusations at each other (yet without ever shouting) or even use their fists.

One issue which is so difficult to live with and to express is the kind of historical experience which has constructed collective identities but in a very traumatic way. When I asked my Native Alaskan friends how they managed to combine their Aleut or Yupik culture, the memory of the partial destruction of their pre-contact culture through contact with Russian traders and their profoundly entrenched Orthodox Christian faith (as strong among almost half of indigenous Alaskan communities than Catholicism among Latin American Indians) my friends’ reaction would be to end the conversation with a remark such as “Oh! that’s old history. We don’t talk about it anymore”. When you hear something like that, don’t believe it. The past is hidden somewhere in a junk mail file of the soul that has never been emptied out. Finland’s memorial representations suffer from similar trauma, but after events that are even more recent. Twenty years ago, more than a few elderly people could still remember the terrible civil war that marked their childhood from 1918 and beyond. Today, the population over eighty could recall the embarrassing situation of Finland having to fight on the same side as Nazi Germany to protect itself against the threat from the East, then having to sign, for the second time, an unfavorable treaty with the USSR and being humiliated until 1991, when the country was reduced to the status of a quasi-satellite, almost like Romania or Bulgaria, a country with a free-market economy and open borders but always being pressured by the USSR to support its positions in foreign affairs. Solzhenitsyn’s “GULag Archipelago” as well as all other literature banned in the Soviet Union had to be banned by Finnish authorities as well. The Finnish police had to surrender to Soviet border guards any defector who had jumped ship from a Soviet vessel or managed to cross the border into Finnish territory (an extremely rare occurrence since the Soviet-Finnish border was an impenetrable 25 meter thick barrier of barbed wire, watchtowers, electronic sensors and other obstacles).

But repressed memories cannot remain hidden forever, especially in a culturally rich metropolis which prides itself in its historic monuments. Its oldest and most impressive has even been recognized UNESCO World Heritage site: Sveaborg, the old Swedish fortress, also known by its ancient Finnish name of Viapori until 1918 when it was given its most recent name: Suomenlinna. It is pregnant with memories of violence.

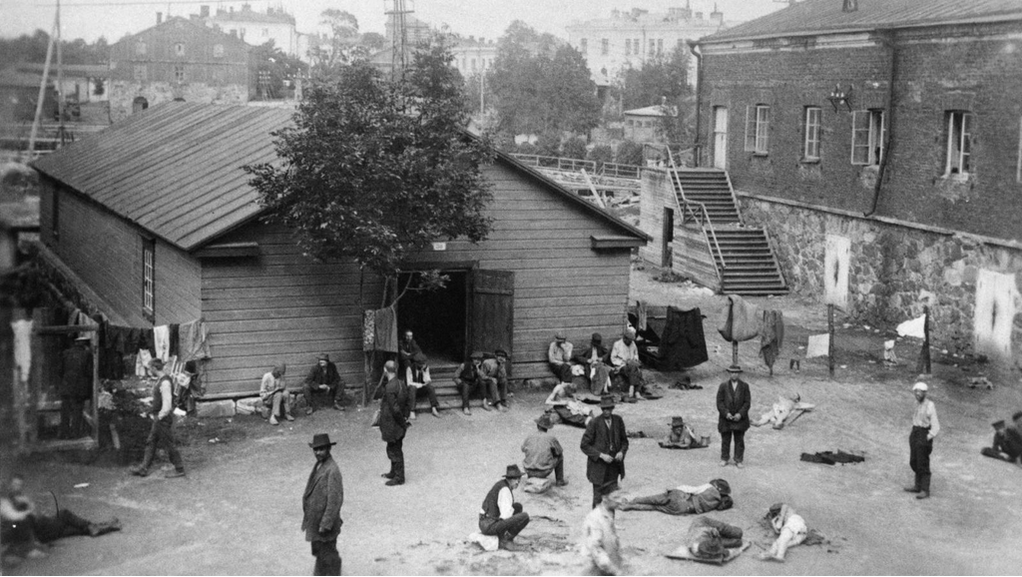

Constructed during second half of the 18th century, named Sveaborg by its Swedish builders, then Vipuri (a Finnish name) when conquered by the Russians in 1808, and finally Suomenlinna ("Fortress of Finland") in 1918 when Finland gained independence, this redoubtable fortified garrison the walls of which surround six islands connected by bridges, is now a UNESCO World heritage site, a park and an array of museums. An almost idyllic area for quiet walks, it still conceals a history of conflict, and painful memories as a POW camp during the Finnish civil war of 1918 and the Finno-Soviet war of 1941-1945.

Suomenlinna appears as a large fortified village built upon six islands connected by bridges, just off the coast where Helsinki stands. Little has changed here since the 18th and 19th centuries. It is a rural version of Saint Petersburg’s Peter and Paul Fortress: the fortifications share the same architectural principles of a star-shaped fortress. But the interior of Suomenlinna is like a Swedish or Russian village (with many well preserved wooden houses) rather than a succession of monuments as you find inside the Saint Peter and Paul Fortress in the center of Saint Petersburg. Suomenlinna hosts several museums. One of the military museums can induce a shock when entering it and discovering a 1918 fighter airplane. The markings on its wings are similar to the Nazi flag. Years before the German NSDAP adopted its infamous symbols, the anti-Communist air force exhibited on its planes the exact same black swastika, the Hakenkreuz with its extremities pointed towards the right, in a white circle, positioned in the exact same geometrical configuration and proportions as the flag of the Third Reich. The only difference is that the flag upon which the frightening symbol has been painted is navy blue instead of red. How this symbol (which remained a part of Finnish militaria until 1945) became imitated by the Nazis is not a very well-known story, probably because many prefer it to be forgotten, as they would like to forget about Hitler’s admiration for their country and its leader Mannerheim (who despised his unofficial but de facto German ally) and the bloodshed that tore the country apart just as it became independent. But this is not an innocent coincidence. Pioneer military aviator count Eric von Rosen, who donated to Finland's air force one of its earliest aircrafts later became a prominent figure in a Swedish Nazi movement. As early as 1906, military personnel serving in Sveaborg, at the time under the Russian flag, mutinied. Their insurrection was violently repressed. In 1918, the Russian Revolution and consequent White versus Red civil war was replicated on Finnish territory, just at the time when Finland proclaimed its independence. Helsinki was the capital of the Reds. The conflict was not as bloody as in the crumbling Russian Empire and emerging Soviet Russia, but in a country like Finland where there lived no more than three million people, nearly 40,000 deaths in less than a year was appalling and could only leave scars in collective consciousness. As in Soviet Russia, arbitrary measures and mass executions were carried out by fanatical elements from both sides. With the victory of the White forces (the “Finno-Whites” as they were called in Soviet history books), tens of thousands of soldiers from the Red forces were detained in prison camps where 11,000 POWs succumbed from ill treatment. The fortress of Sveaborg became one of the best known of those prison camps. This history is reminisced in tracks four and six of the 1998 locally produced album Viapori composed by musician Wolf Larsen in 1998.

Approximately ten thousand prisonners who had fought in the Finnish Red Army or suspected sympathizers including women and children were taken prisonners to Suomenlinna (photos: Museovirasto) where hundreds died from abuse . Soviet POWs received much more humane treatment in the 1940s

Until the end of World War II, the narrative that dominated public discourse was the White’s celebration of their victory over Red Terror. Since the second half of the 20th century, neutral or pro-Red literature and other media have become widespread. “The Socialist dream of freedom, brotherhood, and equal rights came true for three days when Russian gunmen started the mutiny of Viapori in the summer of 1906” proclaims musician Wolf Larsen in his comment to “1906”––track four of Viapori. That track four is different from the rest of the album, an otherwise peaceful progressive symphony. “1906” begins quietly, then rises in a progressive crescendo rhythmed by an increasingly obtrusive number of bass instruments and a military drum, and ends vocally with a violent human voice screaming “tovaritch!”––“comrade!” (the only vocal piece in the album).

But the rest of the album steers you away from the violence witnessed in Sveaborg.

But the rest of the album steers you away from the violence witnessed in Sveaborg.

The peaceful shores of Uusimaa.

Wolf Larsen’s album was actually recorded on the archipelago to which it is dedicated: Seawolf Studios is still one of the rare privately-owned businesses on Suomenlinna. It could be surprising that such an enterprise is located in a place which is very much like a national park. But this is Helsinki, where the world-famous composer Sibelius lived during most of his life and where today, so many local or visiting rock, pop, folk, world and jazz bands perform in concert halls, restaurants or other venues with styles that vary from the wildly acid rock of Lordi to the half-Saami folkloric, half-world music band Angelin Tytöt. Wolf Larsen’s music is a tribute to Suomenlinna and to the sea around it. “Imagine a warm summer day on the ferry to Viapori––a taste of salt in a gentle breeze of south wind, the sunny blue sky and the seagulls flying high…” writes Larsen. Indeed, there is something soothing in Larsen’s electronic melodies, influenced by world music and the kind of lounge CD compilations the Parisian Man Ray and Buddha Bars published for their patrons. It inspires the kind of relaxation that you get from viewing the landscape of Suomenlinna or its neighboring coastline of the region of Uusimaa, whether in the summer or in the winter when, in the words of Larsen, “freezing seawinds pushes the iceblocks against the rugged cliffs of the Susisaari island. Can you hear their silent waltz?”

The presence of almost all the survivors of Red and White veterans in Finland in the 1920s and 1930s, although not an easy coexistence, did not prevent an attempt to bring peace to the country. A compromise was found, mainly thanks to moderate right-wingers and left-wingers, or those that had remained neutral. Thus, all former enemies were able to cohabit and start building a country. Encouraging a culture of cosmopolitanism became a useful strategy.

A doctor of Helsinki University and Sorbonne professor Harri Veivo explains Finnish cosmopolitanism in such a context. The tragedy of Finland, and especially of Helsinki where conflict was particularly violent, was that any representation of the new independent Finland as a united nation was immediately challenged by the terrible civil war.

A doctor of Helsinki University and Sorbonne professor Harri Veivo explains Finnish cosmopolitanism in such a context. The tragedy of Finland, and especially of Helsinki where conflict was particularly violent, was that any representation of the new independent Finland as a united nation was immediately challenged by the terrible civil war.

As a result, the unity of the young state was merely a myth, and the young generation of artists, writers, and intellectuals participating in the revues Ultra, Tulenkantajat and Quosego felt that the cultural and spiritual life of Finland had to be regenerated and the lost link with artistic modernism in Europe re-established. They adopted a strategy of internationalization, seeking to overcome what they perceived as belatedness and critically appropriating the modernistic and avant-garde art movements of the 1910s and early 1920s. While the traditional centers such as Berlin and Paris remained attractive, the young generation also sought contacts with the other new nations, such as Estonia, the other Baltic States, and Czechoslovakia, which were perceived as more vital and interesting than the ‘old’ capitals. The visual arts, architecture, theatre, and literature in these countries were often presented as the models to follow. This decentring or recentring was accompanied by an effort to shift the power balances in Finland by promoting the provincial cities that were left in the shadow of Helsinki. " *

* See the abstract of professor Veivo's paper « Decentred Cosmopolitanism and the Visual Discourse of Modernity in Finland in the 1920s » presented at the Workshop on Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in Avant-Garde and Modernism : The Impact of WW I, Prague (République Tchèque), novembre 2014, http://www.udu.cas.cz/data/user/docs/WWI_abstracts.pdf

The most interesting in Professor Veivo's point is that "Cosmopolitanism was thus not necessarily antagonistic to nationalism, but rather complementary to it". Does this mean, in more simplistic language, that to be a true Finn you must be cosmopolitan? After almost two decades of sharing impressions with other foreigners having lived in Helsinki, I have difficulty imagining that cosmopolitanism and openness to the Other is not an essential trait of Helsinki’s identity.

The Swedish heritage

Above: the tomb of field-marshal Augustin Ehrensvärd (1710–1772) is a monument dedicated to the one who spent the last 25 years of his life of his lifetime building and expanding the fortress of Sveaborg, It still stands on the fortified archipelago renamed Suomenlinna since 1918. During the period when it served as a Russian military base, the tzar's troops left the grave in its place out of respect for their formidable enemy of the previous century.

So this is why the Russian flavor of Helsinki may not only be a symbol of submission to an oppressive neighbor (the kind of enemy that, with the threat that it pauses, could federate an otherwise divided people) but rather an occasion for the inhabitants of Helsinki to manifest an international dimension in their identity.

But I have been discussing Helsinki’s Russian heritage excessively. The Swedish heritage is even stronger.

But I have been discussing Helsinki’s Russian heritage excessively. The Swedish heritage is even stronger.

I mentioned the Russian flavor of the Senate Square. However, at the approach of Christmas, here, on Senate Square and in the entire quarter around it, the historic Helsinki transforms itself into a large Swedish city. One of the most beautiful traditional annual events is an enchanted happening that lights up the eighteen or nineteen-hour long December sub-Arctic night. A procession of thousands of young girls holding a candle and dressed in white gowns like communicants, slowly moves through the streets and avenues towards the Lutheran cathedral. The leader of the procession is crowned with a tiara of lighted candles. It is “Luciadagen” in Swedish or “Lucian päivää” the feast of Saint Lucy. If there is no wind and the flames of the candles do not flicker, this is one of the world’s most astounding and inspiring cultural manifestations of history, culture and spirituality.

The centuries of Swedish rule left a heritage far stronger than the traces of the Russian decades.

The Swedes of Finland remained in the country during the Russian rule as a socially, economically and culturally dominant class. They could have become competitors resisting the Russian conquerors, but being aristocrats, many Swedes, like Mannerheim, and like the barons of German descent in the Baltic states, were easily integrated into the élites of the Russian Empire and in fact, helped maintain an order of social hierarchy in the Grand Duchy. This created much class friction that was behind the motives of the civil war. Direct Finnish-Swedish confrontation, however, erupted in the form of violent inter-ethnic incidents in Finland in its first two decades as an independent state. What resolved this issue was the danger of Soviet invasion which threatened the existence of both Finnish and Swedish nationalisms. The Soviet invasion of 1939-1940—the Winter War—reconciled the two ethnic groups and served, once again, as a factor of ethnic tolerance and of the cosmopolitanism mentioned earlier.

Today the “Swedish Assembly of Finland”, or “Folktinget” is even part of Finland’s institutions. Its website explains that it is an organization

The centuries of Swedish rule left a heritage far stronger than the traces of the Russian decades.

The Swedes of Finland remained in the country during the Russian rule as a socially, economically and culturally dominant class. They could have become competitors resisting the Russian conquerors, but being aristocrats, many Swedes, like Mannerheim, and like the barons of German descent in the Baltic states, were easily integrated into the élites of the Russian Empire and in fact, helped maintain an order of social hierarchy in the Grand Duchy. This created much class friction that was behind the motives of the civil war. Direct Finnish-Swedish confrontation, however, erupted in the form of violent inter-ethnic incidents in Finland in its first two decades as an independent state. What resolved this issue was the danger of Soviet invasion which threatened the existence of both Finnish and Swedish nationalisms. The Soviet invasion of 1939-1940—the Winter War—reconciled the two ethnic groups and served, once again, as a factor of ethnic tolerance and of the cosmopolitanism mentioned earlier.

Today the “Swedish Assembly of Finland”, or “Folktinget” is even part of Finland’s institutions. Its website explains that it is an organization

|

" with the statutory task of safeguarding the Swedish language and the interests of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland. The Assembly participates in the law drafting process and issues statements on topics involving the Swedish-speaking population. Folktinget is a cross-political body – all parliamentary parties with activities in Swedish are members. Folktinget publishes and distributes brochures on linguistic rights and disseminates information on Swedish culture in Finland. In addition, the Swedish Assembly regularly compiles information and statistical reports on the Swedish-speaking Finns, and promotes positive attitudes towards bilingualism through campaigns and events"

http://www.folktinget.fi/en/about/ |

Swedish––often in the form of local dialects––is still the maternal tongue of a little over five percent of the entire population of Finland, a little over six percent of the entire population of Helsinki. This makes the Finnish capital one of the officially bilingual municipalities of the country. All road signs appear in the two languages. Trying to constantly avoid sugar and harmful chemicals when shopping in Helsinki as well as anywhere in the world, my knowledge of German allowed me to decipher the list of ingredients printed not only in Finnish on the labels of processed food but also in Swedish which is not very close to German, but certainly much closer to the finno-ugric linguistic group to which belongs Finnish as well as the languages of the indigenous Saami, of the Karelians, Estonians, of several indigenous populations of the Russian North-West and of large lands of Western Siberia and also Hungarian. Arriving into the capital on a train you will hear “Helsinki – Helsingfors” on the loudspeakers as all official announcements in public places and suburban trains are always broadcast in both Finnish and Swedish. My favorite announcement in a train is the incredibly musical “Huopalahti-Hoplax” pronounced in the velvety feminine voice of an alto that you hear in all trains. Which is why the voice of a voluble woman sounded strangely familiar when I went into a babershop, for the first time, near Aleksanterinkatu––another one of the most important avenues (one of the rare ones without trees).

Brick buildings (above) built in the national romantic style influenced by Northwestern European merchant cities reveal the influence of Swedish culture and the strong Swedish influence over Finland and Helsinki. An important minority of speakers of Swedish, often originating in the elites of the country, explains why Helsinki, like many parts of Finland, is officially a bilingual city using Swedish and Finnish.

The person whose voice sounded so familiar was hanging out with her friend the barber and chatting with him and his clients. She was of the talkative kind and, when she saw that I was a foreigner, immediately engaged in a conversation in English (which so many Finns speak with perfection) about Helsinki and Finland. She was so enthusiastic that I wondered why the main tourism institutions in town hadn’t hired her as their chief salesperson for convincing vacationers to purchase the most expensive holiday package in Helsinki. In fact, she revealed to me that she was indeed important to the tourist industry: not only tourists like me but anyone using public transportation in Helsinki knew her as the voice making all the announcements at a train’s approach to any station. Like any ridiculous fan asking Sean Connery to say “Bond, James Bond” I asked her to repeat “Huopalahti-Hoplax”.

“Huopalahti-Hoplax”.

That was her, indeed.

She had a beautiful radio-friendly voice, but I also remarked on how the Finnish language is as melodious as Italian (what soon confirmed my impression was hearing the opera Juha, composed by Aarre Merikanto in the early 1920s but produced only in 1963). Although not as lithe as Finnish with all its vowels frequently dancing a reel with the consonant “L”, Swedish is not as rigid or harsh as Klingon. If you are a fan of Bergman movies and have heard Bibi Anderson’s joyful outbursts or other Bergman actors say “min älskade” (”my beloved”) as many times as I have, you know that Swedish can be pleasing to the ear. My new acquaintance’s voice and diction served Bergman’s language very well. She explained a few things to me about her town and the Swedish, Russian or Saami cultural traits that coexist in the education of each Finn. Although the large majority of Finns had little or no ties with Sweden––for those who did, it was often a sign of belonging to the ruling classes and even the aristocracy––many among them learned Swedish. All over the country, bilingualism often manifested itself in different forms.

“Huopalahti-Hoplax”.

That was her, indeed.

She had a beautiful radio-friendly voice, but I also remarked on how the Finnish language is as melodious as Italian (what soon confirmed my impression was hearing the opera Juha, composed by Aarre Merikanto in the early 1920s but produced only in 1963). Although not as lithe as Finnish with all its vowels frequently dancing a reel with the consonant “L”, Swedish is not as rigid or harsh as Klingon. If you are a fan of Bergman movies and have heard Bibi Anderson’s joyful outbursts or other Bergman actors say “min älskade” (”my beloved”) as many times as I have, you know that Swedish can be pleasing to the ear. My new acquaintance’s voice and diction served Bergman’s language very well. She explained a few things to me about her town and the Swedish, Russian or Saami cultural traits that coexist in the education of each Finn. Although the large majority of Finns had little or no ties with Sweden––for those who did, it was often a sign of belonging to the ruling classes and even the aristocracy––many among them learned Swedish. All over the country, bilingualism often manifested itself in different forms.

|

|

|

Sveaborg-Viapori-Suomenlinna is the most visible and impressive architectural testimony to the centuries of Swedish rule, but many other traces remain.

Sederholm House, the smallest one on the southeast corner of Senate Square is the oldest stone building in Helsinki. A light-blue, rectangular, two story building decorated with discreet white trimmings and topped by a gambrel roof, it hosts the Helsinki City Museum. Many town houses that looked like rectangular structures with their longest side on the ground, often built in granite or cement or painted in grey or white, manifest the Swedish influence over Helsinki and its suburbs well into the Twentieth century. In the countryside, the red-painted log structures of manors and churches were typically Swedish. It is necessary to travel far into rural Finland to find such, but in the Western outskirts of Helsinki, the old church of Karuna with its typically Scandinavian belfry, Kahiluoto Manor, and Iisalmi parsonage stand on the island of Seurasaari.

Sederholm House, the smallest one on the southeast corner of Senate Square is the oldest stone building in Helsinki. A light-blue, rectangular, two story building decorated with discreet white trimmings and topped by a gambrel roof, it hosts the Helsinki City Museum. Many town houses that looked like rectangular structures with their longest side on the ground, often built in granite or cement or painted in grey or white, manifest the Swedish influence over Helsinki and its suburbs well into the Twentieth century. In the countryside, the red-painted log structures of manors and churches were typically Swedish. It is necessary to travel far into rural Finland to find such, but in the Western outskirts of Helsinki, the old church of Karuna with its typically Scandinavian belfry, Kahiluoto Manor, and Iisalmi parsonage stand on the island of Seurasaari.

"The Silent Waltz"

|

Seurassari is an island a few yards off the coast, where the wooded areas of Helsinki have already become a dense forest. Since the early 20th century, it hosts an open-air museum where several dozen examples of rural wooden architecture that have been reconstructed after having been entirely dismantled and transported from all parts of Finland. Walking around this artificial village and walking in and out of beautiful log houses provides an impression of living a strange dream. The quietness is particularly eerie in the winter when the snow covers everything and imposes such a silence that anyone suffering for years from the worst case of insomnia should plan a vacation to Helsinki in December or January and rent one of the numerous cabins in the far suburbs. After a brisk hike with cross-country skis, a sauna and a glass of hot wine, sleeping in the most perfect silence with eighteen hours of darkness will heal any insomnia. It is only one of the many joys of the Great North.

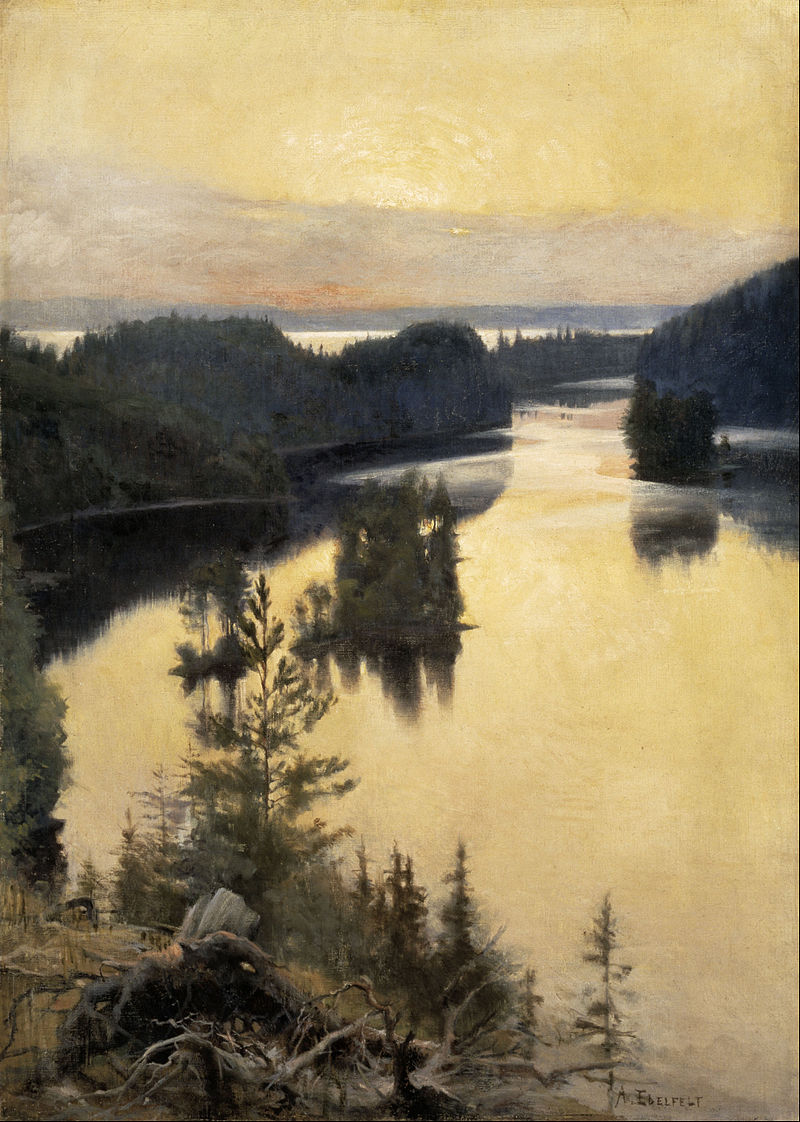

Albert Edelfelt's "Kaukola Ridge at Sunset" (1889–90), is one of the most famous paintings on exhibit at Helsinki's Ateneum Art Museum. The 83 x 116.5 cm canvas is particularly iconic. Never having built spectacular architectural monuments or large cities, the essentially rural Finns, a colonized quasi-Indigenous population, affirmed their identity and the richness of their civilization with two iconic forms of art. One was the Kalevala, a masterpiece of oral literature and mythology told by female bards, discovered, recorded and published in the early-mid 1800s by Finnish ethnographer Lönnrot, to the world's amazement. It is for Finns what The Illiad and Odyssey are for Greeks or what The Divine Comedy is for Italians. The other pillar defining Finland is landscape painting. It affirmed itself as the representation of what is the most valuable treasure and the common denominator upon which is built Finnish identity. It obviously shaped the minds behind Helsinki's urban landscaping.

|

And it is one of the reasons why I love Helsinki in the winter. Of course, its old-fashioned shop windows decorated for Christmas so that children (not rich tourists, like in Paris) would enjoy the season spirit, creates a fairy-tale atmosphere that has been banned from the great cities of the world unless it is fake, overdone, and commercial like in Disneyland...

Seurassari is an island a few yards off the coast, where the wooded areas of Helsinki have already become a dense forest. Since the early 20th century, it hosts an open-air museum where several dozen examples of rural wooden architecture that were reconstructed after having been entirely dismantled and transported from all parts of Finland. Walking around this artificial village and walking in and out of beautiful log houses provides an impression of living a strange dream. The quietness is particularly eerie in the winter when the snow covers everything and imposes such a silence that anyone suffering for years from the worst case of insomnia should plan a vacation to Helsinki in December or January and rent one of the numerous cabins in the far suburbs. After a brisk hike with cross-country skis, a sauna and a glass of hot wine, sleeping in the most perfect silence with eighteen hours of darkness will heal any insomnia. It is only one of the many joys of the Great North.

And one of the reasons why I love Helsinki in the winter. Of course, its old-fashioned shop windows decorated for Christmas so that children (not rich tourists, like in Paris) would enjoy the season spirit, creates a fairy-tale atmosphere that has been banned from the great cities of the world unless it is fake, overdone, and commercial like in Disneyland...