Nature & Cultures, the American University of Paris geographic magazine for global explorers - No. 7

Catherine Lanfranchi-de Wrangel, author of a rich article on Ferdinand von Wrangel Associate Professor of the University of Nantes, is a leading figure of higher education in Brittanny. Her teaching, research and leadership positions are countless. She has also organized numerous international conferences. An expert in Russian and in Italian languages and cultures, she also has expertise in the culture and history of the Russian Empire and particularly of the Baltic states. She has been researching the life of Ferdinand von Wrangel with her husband Dr. Alexis de Wrangel, descendant of the famous 19th Century explorer from Estland, now Estonia.

Wrangel : Narrative of an Expedition to the Polar Sea, in the years 1820, 1821, 1822 & 1823, London, James Madden & co., 1840

Introduction

Travel literature, even if it is very old (we can think for example of Marco Polo's book, Il milione 1 which relates the journey of the Venetian traveler in China in the second half of the 13th century) knows a very important development at the end of the 18th and throughout the 19th century.

In this period, the influence of geography, the valorization of travel (voyages for exploration or study), as well as the high reputation of the of an explorer, and the success of the exploration literature explain the increase of the public's interest for the subject and the multiplication of publications in this field.

These reasons explain the success of the publication in 1827 of the travel diaries[i] of the German-Baltic seafarer and explorer Ferdinand von Wrangel, a text reworked and published in 1839 in German[ii] and then translated into English[iii] in 1840, into Russian[iv] (1841) and finally into French [v] (1843, republished in 1860 and in 2011)

Travel literature, even if it is very old (we can think for example of Marco Polo's book, Il milione 1 which relates the journey of the Venetian traveler in China in the second half of the 13th century) knows a very important development at the end of the 18th and throughout the 19th century.

In this period, the influence of geography, the valorization of travel (voyages for exploration or study), as well as the high reputation of the of an explorer, and the success of the exploration literature explain the increase of the public's interest for the subject and the multiplication of publications in this field.

These reasons explain the success of the publication in 1827 of the travel diaries[i] of the German-Baltic seafarer and explorer Ferdinand von Wrangel, a text reworked and published in 1839 in German[ii] and then translated into English[iii] in 1840, into Russian[iv] (1841) and finally into French [v] (1843, republished in 1860 and in 2011)

|

The development of geography and its positioning as a science

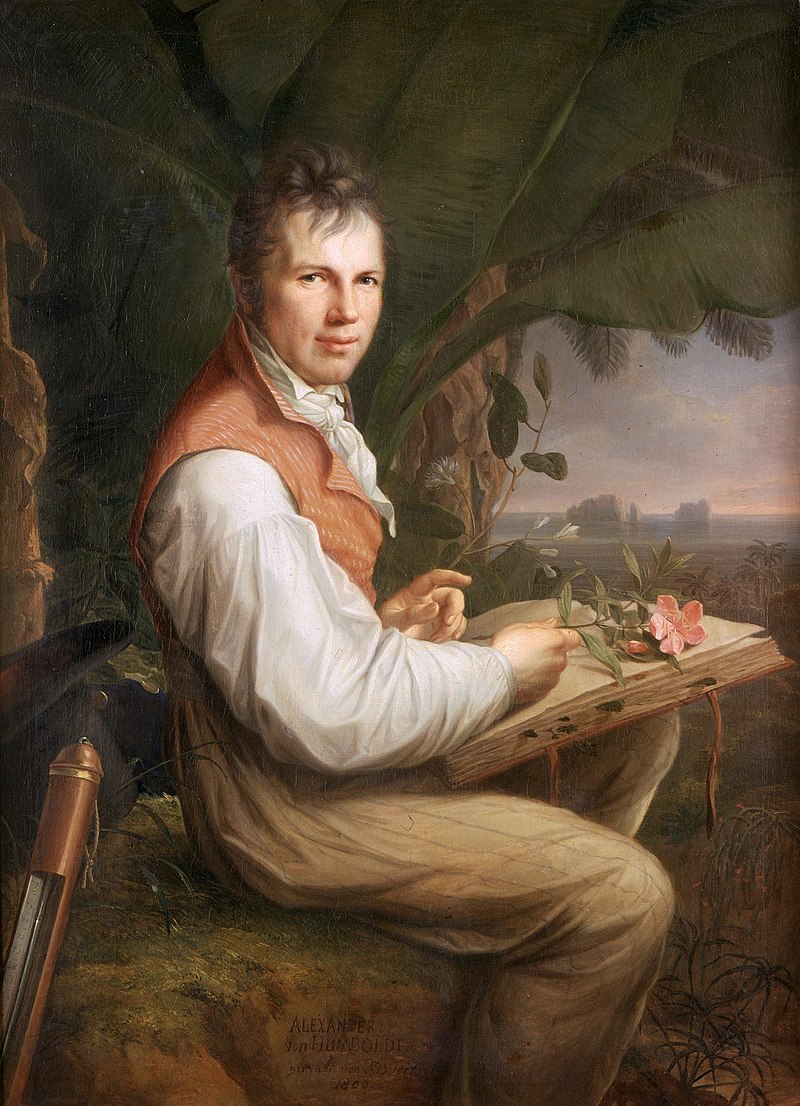

In Europe, the political and social upheavals of the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries brought about profound transformations in the management of national spaces and territories. It was then that the elements that would lead to the affirmation of national identities in the second half of the 19th century were established. The triumph of nation-states implies a rationalized knowledge and management of their territory and resources. The Russian Empire did not escape this process. Vast parts of its territory (especially in northern Siberia) remained completely unknown and unmapped. It is not even known whether the extreme tip of the continent was connected to the west of the American continent and the search for the Northeast passage was in full swing. In order to control and administer the territories in the far north, which had recently been annexed by Cossacks and fur traders, it was necessary to know them and map them. Because of these necessities, geography became a field of knowledge the importance of which was constantly growing and the practice of which was profoundly transformed. Next to the French model of "cabinet" geography (where the geographer does not travel in the field), a geography of wandering, of essentially Germanic inspiration, emerged which, influenced by romanticism, advocates mobility in the regions it studies. Travel (and even more so, exploration) then became essential. It thus appears as the founding act of modern geography, with Carl Ritter and Alexander von Humboldt as its main representatives, whose peregrinations will create a new school of thought. Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), considered almost unanimously as the father of modern geography. One of the greatest travelers in the two centuries in which he successfully imposed field work as an efficient method

|

The success of the explorer figure

In this context, the figure of the explorer takes on a particular importance.

As Numa Broc notes: "The explorer undoubtedly represents, alongside the scientist, the engineer, the missionary, one of the key figures, one of the archetypes of the European 19th century "[vi]

At that time, indeed, his role was multiple and fundamental. He was expected to advance geographical, anthropological and archaeological knowledge, but also (in a period of colonial expansion) to discover and evaluate exploitable riches. This "hero of our time", tireless solitary discoverer, composes a glorious story, proposed as well in the literature of adventure as in the popular imagery.

Ferdinand von Wrangel synthesizes well this evolution of geography and of the figure of the explorer, which allows to explain the reasons of the success of his writings.

In this context, the figure of the explorer takes on a particular importance.

As Numa Broc notes: "The explorer undoubtedly represents, alongside the scientist, the engineer, the missionary, one of the key figures, one of the archetypes of the European 19th century "[vi]

At that time, indeed, his role was multiple and fundamental. He was expected to advance geographical, anthropological and archaeological knowledge, but also (in a period of colonial expansion) to discover and evaluate exploitable riches. This "hero of our time", tireless solitary discoverer, composes a glorious story, proposed as well in the literature of adventure as in the popular imagery.

Ferdinand von Wrangel synthesizes well this evolution of geography and of the figure of the explorer, which allows to explain the reasons of the success of his writings.

|

Ferdinand von Wrangel

Ferdinand Petrovitch von Wrangel, of German-Baltic origin, was a Russian explorer, seafarer and administrator born in 1797 in Pskov; he died in 1870 in Dorpat, Estonia. Following the premature death of his parents, he was sent to the Naval Cadet Corps in St. Petersburg, from which he graduated in 1815 as valedictorian. He made several circumnavigations, first as a young officer under the command of Captain Vasily Golovnin, then as a ship's commander. In 1827 he was appointed governor of Alaska and the Russian colonies in California. Then he became general manager of the RAK (Russian-American Company which exploited the Russian colonies in America). He became Minister of the Navy in 1855 and managed the rebirth and modernization of the Russian Navy after the Crimean War in 1854.Paragraph. Cliquez ici pour modifier. Wrangel in Naval uniform in his late thirties or mid-forties.

|

Chetyrokhstolbovoy Island (i.e. "Island of the Four Pillars") one of the Medvezhyi Islands, explored by Wrangel with Matiushkin.

Photo by Ansgar Walk (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

Photo by Ansgar Walk (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

|

His exploration of the Siberian coastlines

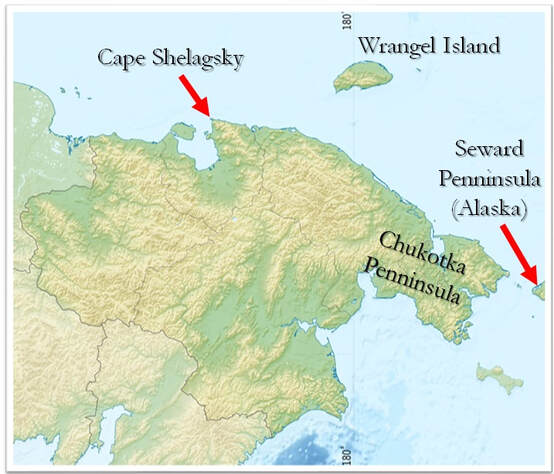

The geography of this part of the polar coast remains particularly uncertain while at the same time, the northern coasts of America had been the subject of scientific works conducted by Ross, Parry and Franklin. It is what determined the Emperor Alexander I to give the order to send two naval officers to the mouths of the Yana and Kolyma rivers in order to discover lands that were thought to exist and to survey the coasts of the Ice Sea, from the Oleniok, towards the east, beyond the North Cape. After his first circunavigation (from 1817 to 1819 ) aboard the frigate Kamchatka commanded by Vassili Golovnin during which he achieved a partial cartography of the Aleutian Islands and the coast of Alaska, he was offered by the Minister of the Navy Traversay to lead the Kolyma expedition from 1820 to 1824 the mission of which was to explore and map the unknown coastal areas of the Glacial Sea, north of Kolyma and Cape Chelagski as well as to observe the customs of the populations met during the exploration. |

Fyodor Fyodorovich (1799-1872), who worked closely with Wrangel during his explorations, was a Russian navigator, Admiral (1867), and a close friend of poet Aleksandr Pushkin, who had studied with him at the famous Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum.

|

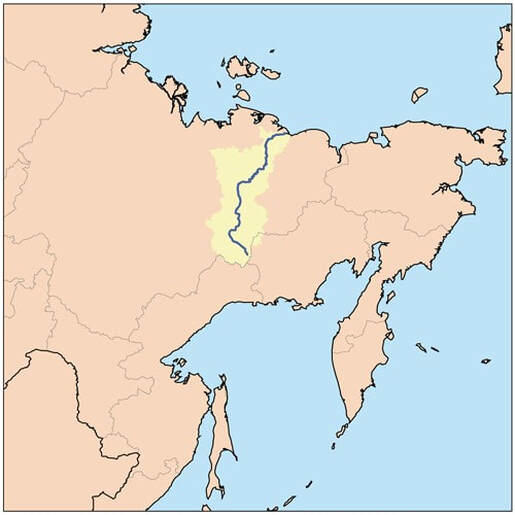

He was to head towards the mouth of the Kolyma River, then West to the mouths of the Indigirka River and east to Kolychin Island on the Chukchi Sea. He took with him the midshipman Matiushkin (who had served aboard the Kamchatka) and the naval officer Kozmin as well as the naturalist Kiber. His comrade Pyotr Anjou was placed at the head of the other expedition, which was ordered to proceed to the mouth of the Yana river, to reconnoiter the Kotelny and Fadeieev islands (situated in New Siberia, in the archipelago now called Anjou) and to survey the coastline between the mouths of the Indigirka and Oleniok rivers.

With these instructions, during his expedition, Wrangel established the existence of an open sea and the probability of the presence of an unknown island off the coast, in the Arctic Ocean, which would later receive his name. He also collected a great amount of data on glaciology, mineralogy, geomagnetism and climatology but also on the populations of these regions as well as on their natural resources. All this information was to appear later in appendices as well as in his notebooks published in 1827 in Berlin as well as in his account of 1839 Reise des kaiserlich-russischen Flotten-Lieutenants Ferdinand v. Wrangel längst der Nordküste von Sibirien und auf dem Eismeere, in den Jahren 1820 bis 1824, then in its various translations in Russian (1841) then in French (1843) : Le nord de la Sibérie.Voyage parmi les peuplades de la Russie asiatique et dans la mer glaciale [vii]. Pyotr Fyodorovich Anjou (1796–1869), close expedition companion of Ferdinand von Wrangel, Arctic explorer and admiral of the Imperial Russian Navy.

|

Travelling upriver on the Indigirka, Wrangel and his companions reached extremely remote areas where today stands Ust-Nera (left), Uus Ñara in the Indigenous language, located in one of the coldest permanently inhabited regions on Earth, Ust-Nera is approximately 870 kilometers (540 mi) northeast of the republic's capital, Yakutsk (photo by LoLand, CC BY-SA 3.0). Right : a view of the Oymyakon region (photo by Maarten Takens. CC BY-SA 2.0)

|

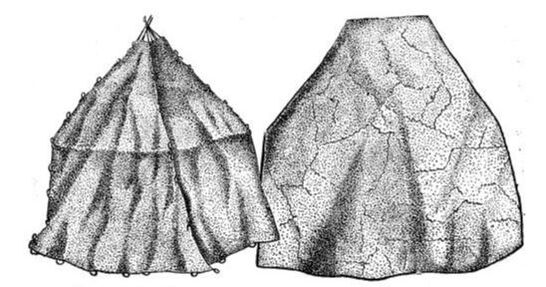

Travelling yurts used by Wrangel in his expeditions

|

The travel notebook

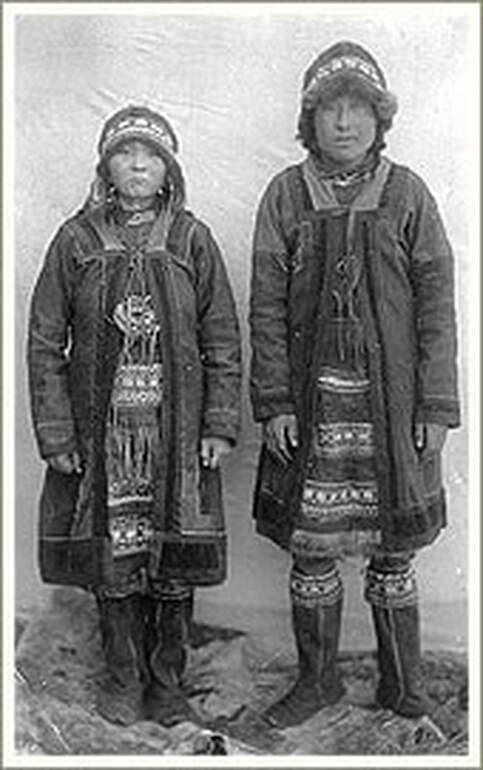

The goals of such writings are varied: to keep a memory of the events that occurred during the voyage, to compile scientific information the collection of which had been planned, to serve as a basis for the establishment of administrative reports intended for the supervisory authority. The first writings of Ferdinand consist of notes in German (and in Russian), taken during his expeditions on the shores of the Glacial Sea, written every evening during the bivouacs, with graphite (the ink risking to freeze by these polar temperatures) on thick blue or white paper and put in order at his return to his base camp, Nijny-Kolymsk, before being used for the drafting of the reports addressed every month by estaffette to the Ministry of the Navy in Saint Petersburg. These notes contain the handwritten description of the accomplished stages of the expedition, the scientific statements carried out (meteorological, magnetism, hydrology, observation of the fields of ice...) as well as the botanical, zoological, mineralogical annotations, etc... One finds there various types of expression---graphic (by the means of diagrams and drawing), statistical (many tables and statements of scientific information appear there), descriptive (descriptions of plants, animals, geological phenomena). Ferdinand includes drawings (sledges and dog teams, campsites...). He also sends to the minister his requests (budget to buy food and dogs, authorizations to undertake complementary explorations...). But besides these official documents, these road books constitute a private diary where he also records all his observations, his remarks as well as the account of his days. He then shares his personal feeling on the encounters which he experiences, the situation of the area, that of the Chukchi populations which live there, etc... But this travel diary, by its immediacy and its spontaneity is not however comparable to the more complete travelogue written more elaborately, released later. In particular, Wrangel will integrate in this last work the contents of letters sent to his friend Lütke from 1820. The North of Siberia thus offered a double opportunity: to write a work which would be at the same time scientific and appealing to a public interested in polar explorations. This was to produce a hybrid text which was to enjoy a certain success, as testified by the successive reissues. Six Even women photographed in the early 1900s were hardly any different from the Indigenous populatrions encountered and described by Wrangel. Evens were called Lamuts in his day.

|

The exploration story

In Ferdinand's case, the shift from the exploration notebook to the exploration narrative is under a double influence: that of German romantic ideology and that of Alexander von Humboldt

The passage from one genre to the other is accomplished in an analytical and discursive mode, but not iconographic. In his final text, Ferdinand inserts very few cartographic surveys, drawings or diagrams. However, he adds in an appendix numerous tables of temperature, hygrometry etc... that the reader is free to consult or not.

In Ferdinand's case, the shift from the exploration notebook to the exploration narrative is under a double influence: that of German romantic ideology and that of Alexander von Humboldt

The passage from one genre to the other is accomplished in an analytical and discursive mode, but not iconographic. In his final text, Ferdinand inserts very few cartographic surveys, drawings or diagrams. However, he adds in an appendix numerous tables of temperature, hygrometry etc... that the reader is free to consult or not.

The Indigirka basin (left, in blue surrounded by beige; ) and the North-East extremity of Siberia (right, Map by Das steinerne Herz Modified by N&C cartography).

Writing together: a practice adopted by the Romantics

In several of his works, Ferdinand still uses this joint writing: several chapters of Physikalische Beobachtungen während seiner Reisen auf dem Eismeere in den Jahren 1821, 1822 und 1823 are coauthored in this way with Matiushkin and by Kuzmin, who wrote from their own notes.

This fragmentary composition of a more comprehensive work expresses the Romantic ideology's desire to vary and combine different and complementary points of view and to advance knowledge through a diverse mode of fertilization, as in the Athenäum, where several writings that were found were anonymous.

In order to transform the text of his exploration notebooks into a travelogue, Ferdinand also uses particular writing techniques. The dramatization of the narrative constitutes one of them.

In several of his works, Ferdinand still uses this joint writing: several chapters of Physikalische Beobachtungen während seiner Reisen auf dem Eismeere in den Jahren 1821, 1822 und 1823 are coauthored in this way with Matiushkin and by Kuzmin, who wrote from their own notes.

This fragmentary composition of a more comprehensive work expresses the Romantic ideology's desire to vary and combine different and complementary points of view and to advance knowledge through a diverse mode of fertilization, as in the Athenäum, where several writings that were found were anonymous.

In order to transform the text of his exploration notebooks into a travelogue, Ferdinand also uses particular writing techniques. The dramatization of the narrative constitutes one of them.

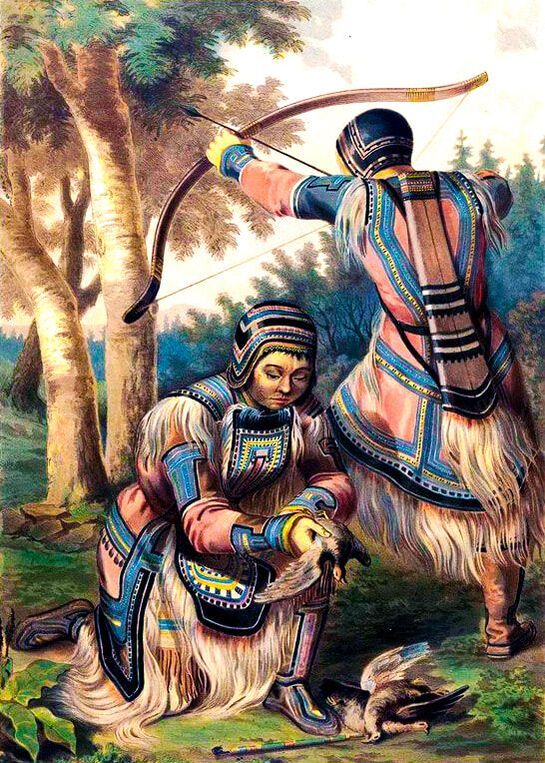

The Evenks (left, still called Tunguz until recently) and Yukaghirs (right) were among the other Indigineous populations encountered in the Arctic and East-interior regions of Siberia by Wrangel.

|

|

The dramatization of the narrative and the aesthetics of the sublime

In Le Nord de la Sibérie, voyage parmi les peuplades de la Russie asiatique et dans la mer Glaciale, Ferdinand relates a number of dramatic episodes that occurred during his expeditions, such as the attack on the camp by bears[viii], the search for the unknown island[ix], the episode where they were lost in the snowstorm or on the ice floe[x].... The danger and violence of the elements as well as of animals and men, the reactions and fears that they inflict upon the mind of the exporter thus become constitutive of the narrative and delimit parts of it, wheras they may have been otherwise only objective and sometimes not very circumstantial accounts in the notebooks.Paragraph. Cliquez ici pour modifier. The Chuckchi (represented here by Louis Chroris, travelling in 1816-1817 aboard the Riurik during another Russian expedition to the Noerth Pacific) are the Natives of the North-East extremity of Siberia, the Chukotka Penninsula, also explored by Wrangel.

|

This dramatization of the narrative also goes hand in hand with multiple lyrical descriptions of Siberian and Arctic landscapes that present the latter as places where the terrible competes with the sublime, thus introducing a very perceptible dramatic tension.

"The general aspect of Cape Chelagsk and the sea that surrounds it is the most horrible that one can imagine! These dark and black rocks, at the foot of which is a sea chained by an immobile and secular ice, these chains of ice mountains which run on its surface, illuminated by the pale rays of a sun which hardly rises above the horizon, the absence of all that has life, finally the silence of death which reigns in these places, inspire terror: all says to the traveller that he crossed the limit of the habitable world! ».[xi]

"The general aspect of Cape Chelagsk and the sea that surrounds it is the most horrible that one can imagine! These dark and black rocks, at the foot of which is a sea chained by an immobile and secular ice, these chains of ice mountains which run on its surface, illuminated by the pale rays of a sun which hardly rises above the horizon, the absence of all that has life, finally the silence of death which reigns in these places, inspire terror: all says to the traveller that he crossed the limit of the habitable world! ».[xi]

|

The description of this frozen sea frozen in walls that collide instantly reminds the reader of Caspar David Friedrich's painting The Sea of Ice made by the painter in 1823-1824, where the broken wooden hull of a stranded ship is smashed by the gigantic waves of ice that seem to launch themselves at the sky.

It is a similar aesthetic of the sublime that is given to see, indissociable and characteristic of Romanticism and more particularly of the Jena Circle whose participants (Novalis, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Fichte, Schlegel) created new literary canons and imposed different themes from those previously carried by Goethe. Just as in the paintings of Friedrich (born on the Baltic coast in 1774), the narration of dramatic events and the description of beautiful and terrible landscapes alternate and intertwine, thus determining a literary style far from the scientific dryness of the notebooks. |

In Ferdinand's text, the influence of the first romanticism is also discernible

in the choice of the description of very numerous mountain landscapes (terrestrial, in the north of this region of Siberia) or maritime (in the form of gigantic icebergs).

As with the romantics of the Jena circle, the capture of the beauty of nature (and in particular that of the mountains) is indeed an essential theme in Ferdinand's Journey. Admiration for its richness during the short Siberian summer or during the magical spectacle of the northern lights, but also fear in front of its cruelty during the interminable polar winter give rhythm to the text and constitute one of its main characteristics. But Ferdinand is far from being the only one who fills his exploration story with such descriptions.

in the choice of the description of very numerous mountain landscapes (terrestrial, in the north of this region of Siberia) or maritime (in the form of gigantic icebergs).

As with the romantics of the Jena circle, the capture of the beauty of nature (and in particular that of the mountains) is indeed an essential theme in Ferdinand's Journey. Admiration for its richness during the short Siberian summer or during the magical spectacle of the northern lights, but also fear in front of its cruelty during the interminable polar winter give rhythm to the text and constitute one of its main characteristics. But Ferdinand is far from being the only one who fills his exploration story with such descriptions.

The Humboldtian influence and the importance of travel

The era of scientific exploration began in South America with the voyage of Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland from 1799 to 1804. The report of this trip was published in 1810 in German.

Moving in the terrain, following the works of the geographer Ritter and the German school of geography, becomes the sine qua non standard for geografical writing. Humboldt thus definitively moves away from the tradition of cabinet geographers and establishes the necessity to see, to travel and to feel the world in order to understand and describe it.

The era of scientific exploration began in South America with the voyage of Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland from 1799 to 1804. The report of this trip was published in 1810 in German.

Moving in the terrain, following the works of the geographer Ritter and the German school of geography, becomes the sine qua non standard for geografical writing. Humboldt thus definitively moves away from the tradition of cabinet geographers and establishes the necessity to see, to travel and to feel the world in order to understand and describe it.

|

Ferdinand von Wrangel in his old age in the uniform of an admiral.

|

To explore is above all to travel.

Travelling acquires a particular status in the Romantic period and even more so with Humboldt. If the "long-distance" voyage of exploration, such as circumnavigations, is typical of the Enlightenment, the shorter voyage of exploration, practiced on foot, such as the excursion, will be valued by the Romantics. In German, two words describe these activities, different in their practice and their purposes: Reisen and Wandern. Reisen is "to travel" in the purely French sense. To set out on a journey for a specific purpose (e.g. scientific) and to use one or more means of transport over a more or less long period of time. Wandern means to go for a walk, to go on foot, often alone and without any particular goal, to go on an excursion, to walk freely to admire the landscapes and nature, for a few hours or a few days and then to give free rein to one's dreams and imagination. Reisen and/or Wandern---these are also the two activities of Ferdinand de Wrangel during his 4 years in the north of Siberia as testified for example by an excursion that he accomplished on Mount Panteley[xii] |

Since Rousseau and his Reveries of the solitary walker, hikes in the countryside or in the mountains are often associated with an activity of botanical observation. Ferdinand does not fail to do so in this long account of an excursion to Mount Panteley. His attitude there is above all the one of a wanderer who climbs a mountain to enjoy an elevated viewpoint over the surrounding nature and who, in his contemplation, feels a romantic fascination in front of the spectacle of the elements which are unleashed. Like Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), Ferdinand stands on top of the mountain and admires the landscape drowned in a fluffy mist.

Conclusion

Ferdinand's work is part of a certain conception of the act of exploration which will then be transformed during the 19th century. In the first half of the century, under the influence of the Enlightenment and Humboldt, it was still essentially a collection of geological, botanical, ethnological, mineralogical and zoological specimens that constituted a body of knowledge with an encyclopedic and scientific purpose. Little by little, however, the very function of exploration evolved: it became a symbolic desire to appropriate the world (and sometimes even its most material riches through the phenomenon of colonization) and ceased to be a strict scientific program.

The modalities of the exploration narrative followed this change, including the numerous illustrations, photographs, and various representations of the explorers (and the members of their expeditions), erected as emblematic figures of Western superiority and sometimes even as national heroes.

Ferdinand von Wrangel still belongs to the first phase of this encyclopedic and Humboldtian concept of exploration. But precisely because of this latter influence, new elements appear in the travel account he delivers in 1839. The Humboldtian criteria are predominant, allowing the composition of a text that is both scientific and literary. This is what will ensure its success with the public, as evidenced by the translations and republications that will follow one after the other until 2011.

Ferdinand's work is part of a certain conception of the act of exploration which will then be transformed during the 19th century. In the first half of the century, under the influence of the Enlightenment and Humboldt, it was still essentially a collection of geological, botanical, ethnological, mineralogical and zoological specimens that constituted a body of knowledge with an encyclopedic and scientific purpose. Little by little, however, the very function of exploration evolved: it became a symbolic desire to appropriate the world (and sometimes even its most material riches through the phenomenon of colonization) and ceased to be a strict scientific program.

The modalities of the exploration narrative followed this change, including the numerous illustrations, photographs, and various representations of the explorers (and the members of their expeditions), erected as emblematic figures of Western superiority and sometimes even as national heroes.

Ferdinand von Wrangel still belongs to the first phase of this encyclopedic and Humboldtian concept of exploration. But precisely because of this latter influence, new elements appear in the travel account he delivers in 1839. The Humboldtian criteria are predominant, allowing the composition of a text that is both scientific and literary. This is what will ensure its success with the public, as evidenced by the translations and republications that will follow one after the other until 2011.

|

Wrangel never succeeded in discovering the island which he suspected existed and which later explorers named in honir of his acheivements.

Photos by Vitaliy Dvorachenko (left) and Anastasiya Petuhova (left) CC BY-SA 4.0 |

i]Marco Polo.Il milione, BUR, Rizzoli, Milano 2004. Tuction française : Le livre des merveilles Larousse, Paris, 2009

• [ii]Ferdinand von Wrangel : Physikalische Beobachtungen des Capitain-Lieutenant Baron v. Wrangel während seiner Reisen auf dem Eismeere in den Jahren 1821, 1822 und 1823, Berlin, G. Reimer, 1827

[iii] G. Engelhardt : Reise des kaiserlich-russischen Flotten-Lieutenants Ferdinand v. Wrangel längst der Nordküste von Sibirien und auf dem Eismeere, in den Jahren 1820 bis 1824, Berlin, Voss’sche Buchhandlung, 1839

[iv] Ferdinand von Wrangel : Narrative of an Expedition to the Polar Sea, in the years 1820, 1821, 1822 & 1823, London, James Madden & co., 1840

• [v]Фердинанд фон Врангель : Путешествие по северным берегам Сибири и по ледовитому морю, Санкт-Петербург, Типограйия А. Бородияа, 1841

[vi] Numa Broc . Les explorateurs français du XIXe siècle reconsidérés. In: Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, tome 69, n°256, 3e trimestre 1982. pp. 237.

[vii]Ferdinand de Wrangel. Ferdinand de Wrangel. Le nord de la Sibérie. Voyage parmi les peuplades de la Russie asiatique et dans la mer glaciale, entrepris par ordre du gouvernement russe et exécuté par MM. de Wrangel (aujourd'hui amiral) chef de l'expédition Matiouchkine et Kozmine officiers de la Marine Impériale russe. Traduit du russe par le prince Emmanuel Galitzin. Tome I et II. Paris, Librairie D'Amyot, éditeur. 1843

[viii]Ferdinand de Wrangel. Ferdinand de Wrangel. Le nord de la Sibérie. Voyage parmi les peuplades de la Russie asiatique et dans la mer glaciale, Op, Cit, P. 289, 290

[ix]Ibid, p.295

[x]Ibid, p. 320

[xi]Ibid, p. 232, 233

[xii]Ibid, T. II, p. 143

• [ii]Ferdinand von Wrangel : Physikalische Beobachtungen des Capitain-Lieutenant Baron v. Wrangel während seiner Reisen auf dem Eismeere in den Jahren 1821, 1822 und 1823, Berlin, G. Reimer, 1827

[iii] G. Engelhardt : Reise des kaiserlich-russischen Flotten-Lieutenants Ferdinand v. Wrangel längst der Nordküste von Sibirien und auf dem Eismeere, in den Jahren 1820 bis 1824, Berlin, Voss’sche Buchhandlung, 1839

[iv] Ferdinand von Wrangel : Narrative of an Expedition to the Polar Sea, in the years 1820, 1821, 1822 & 1823, London, James Madden & co., 1840

• [v]Фердинанд фон Врангель : Путешествие по северным берегам Сибири и по ледовитому морю, Санкт-Петербург, Типограйия А. Бородияа, 1841

[vi] Numa Broc . Les explorateurs français du XIXe siècle reconsidérés. In: Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, tome 69, n°256, 3e trimestre 1982. pp. 237.

[vii]Ferdinand de Wrangel. Ferdinand de Wrangel. Le nord de la Sibérie. Voyage parmi les peuplades de la Russie asiatique et dans la mer glaciale, entrepris par ordre du gouvernement russe et exécuté par MM. de Wrangel (aujourd'hui amiral) chef de l'expédition Matiouchkine et Kozmine officiers de la Marine Impériale russe. Traduit du russe par le prince Emmanuel Galitzin. Tome I et II. Paris, Librairie D'Amyot, éditeur. 1843

[viii]Ferdinand de Wrangel. Ferdinand de Wrangel. Le nord de la Sibérie. Voyage parmi les peuplades de la Russie asiatique et dans la mer glaciale, Op, Cit, P. 289, 290

[ix]Ibid, p.295

[x]Ibid, p. 320

[xi]Ibid, p. 232, 233

[xii]Ibid, T. II, p. 143

Paragraph. Cliquez ici pour modifier.

Paragraph. Cliquez ici pour modifier.

Paragraph. Cliquez ici pour modifier.