The N&C Review Section.

|

“Texts, photographs, links and any other content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.”

|

50 Years ago, James Michener published his iconic Centennial, a novel of the American West

Author James Michener and three of the editions of his best selling historic novel: the cover of the original hardcover edition, the first pocket paperback edition and the 2015 paperback version with an introduction by Steve Berry.

50 years ago, as America was preparing for its bicentennial celebrations, James Michener, a celebrated author of historic novels, published a monumental work of fiction that many consider his best. Centennial skyrocketed to the very top of the best seller lists of 1974. At the time, Americans were realizing that the war of Vietnam was all but lost. Many doubts about America's identity were troubling scores of U.S. citizens. The civil rights movement and other progressive initiatives seemed to be stagnating, especially after the landslide election of Richard Nixon representing a strong grassroots conservative reaction, almost immediately followed by the Watergate scandal. But this was also a time, during these pre-celebration months, when the beauty of America, its landscapes and its people of all races and faiths, was celebrated in the media with slightly greater maturity and self-criticism than before. A documentary series by Alistair Cook or the pages of the National Geographic that had never been of such inspiring quality in its texts and photos learned how to comment on the history and culture of what the French called “l’ Amérique profonde” without the pitfalls of nationalism and White supremacy. James Michener's Centennial is iconic of that period, with a deeper critical outlook.

|

Author James Albert Michener attends an observance commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Location: Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Michener, a middle-aged veteran of the war in the Pacific, became known to the public through his Tales of the South Pacific and Return to Paradise (two collections of essays on the same theme). The success of his first historic novel, Hawaii, with which he created the genre of the historic-geographic novel covering millenia of natural history and human historic geography is what made him one of the best-selling authors American writers of the 1960s to the present. Photo. by Robert Wilson (US Navy).

|

Born in 1907 James Albert Michener (… 1997), raised in a rural environment by a family of Amish farmers, came very late to literature in his forties. Tales of the South Pacific, his first book, was a collection of short stories based on his personal observations and experiences in the Pacific islands during his life there as an officer during World War Two. The great diversity of populations, the profound interaction between people of different races confronted to racism and racial tensions, and the beauty of the landscapes, were the central themes that would become Michener's signature in almost all his future works of fiction. Already very successful in the bookstore, Tales of the South Pacific were adapted by Rogers and Hammerstein (creators of the king and I, Oklahoma, and The Sound of Music) into a musical which became one of the greatest hits of Broadway’s history, and later, a very popular movie.

After a few other novels and a second collection of short stories, Michener returned to the Pacific islands with a historic novel, Hawaii. With this opus magnus, Michener inaugurated an entire new genre in literature. Instead of covering a century or two, or three or four generations of the same family, Hawaii tells the stories of several families of different backgrounds and races intertwined over… 1100 years! Hawaii begins with the first Polynesian explorers to leave Bora Bora and settle in the Hawaiian archipelago in the 9th century, then follows the destiny of their descendants as waves of new settlers arrive between the 1700s and the late 1950s. Also, the novel concentrated exclusively on the local human geography. Michener’s second novel to adopt this type of narration was Centennial which focused on the story of the region of the Platte river in Colorado. The titles of Michener’s next historic novels immediately revealed the places where he was taking his readers: Chesapeake, Poland, Alaska, Texas, Caribbean. The Source was about Israel from Biblical times to the 1960s and The Covenant told the story of South Africa from the 1600s to the late 1970s (the novel was banned by the South African government until the end of Apartheid). The work of research that took years before Michener’s manuscripts would be completed after challenging travels across the terrain (Michener had a mobility impairment and was already a senior citizen when he wrote most of his historic novels), then in libraries, and consulting dozens of experts (historians but also geologists, geographers, ethnographers and other specialists of the region) was such a titanic task that only a very few number of authors have had the courage to invest the same energy in producing similar novels in the genre created by Michener: Edward Rutherfurd (Sarum, Dublin: Foundation, Ireland: Awakening, London, Paris, New York, China) and

|

(with much less media coverage) David Cruise and Allison Griffiths (Vancouver). With a a total of 70 weeks on The New York Times best-sellers list (number one for 24 weeks) Centennial, remains either Michener’s bestselling book or in second position after Hawaii (53 weeks at the number one position, #54 as on the day of publication of this issue of Nature & Cultures on Amazon.com vs. for Centennial’s #100 in Fiction Sagas -- not bad for two books from fifty and sixty-four years ago!).

There is something almost biblical about the way time flows in James Michener’s Centennial :

When the earth was already ancient, of an age incomprehensible to man, an event of basic importance occurred in the area which would later be known as Colorado.

To appreciate its significance, one must understand the the structure of the earth, and to do this, one must start at the vital center.

Since the earth is not a perfect sphere, the radius from center to surface varies. At the poles it is 3950 miles and at the equator 3963. At the time we are talking about, Colorado lay about the same distance from the equator as it does now, and its radius was 3956. Those miles were composed in this manner.

At the center then, as today, was a ball of solid material very heavy and extremely hot, made-up mostly of iron…

Thus, the story begins even before the time of dinosaurs telling how the geology of Colorado formed over millions of years which already makes the narration relevant to the characters that will be found in the chapters about the 19th century miners and the agriculturalists. This natural history ends with the animals of Colorado, concluding with the story of an old widowed female beaver finding a new companion and the digging a new home under the banks of the Platte River. This last episode of the chapter on natural history also seems to preclude a murder mystery affecting modern lives in the 1970s when the narrator sees one of the local oligarchs removing a mysterious bag hidden where centuries earlier the beaver couple dug its burrow. The narrator, a historian writing a book about the town of Centennial--a barely veiled self-portrait of Michener--whose story we follow at the beginning or at the end of each chapter as he is conducting his research, is the thread that links all the stories together from the eras before the dinosaurs to the 1970s. The lives of the animals, their ecosystem, their behavior, and their interaction with the seasons introduces us to the indigenous hunter gatherers, whose nomadic way of life is described in great detail. Arapaho chief Lame Beaver is the first character in the novel. His story is told from his youth to his old age. The first European to appear in the region is the Frenchman trapper canoeing up the Platte River, Pasquinel, who will marry Clay Basket, Lame Beaver’s daughter. These three characters will be ancestors of all the other main characters of the novel up to the 1970s. These are the brothers Jake and Marcel Pasquinel, who grow up with the Arapahos and are tormented by their double heritage, suffering from the racism of the first White settlers. Their sister Lisette Pasquinel marries Levi Zendt, the very first individual to settle on the spot of what will become his trading post, then the settlement and town of Centennial. His escape from his Amish family in Pennsylvania, his first marriage and his unsuccessful attempt to move to California offers remarkable descriptions of the wagon trains that crossed the continent in the 1840s. Michener’s realism cleans the readers mental maps from all the clichés attached to the stories of wagon trains depicted in western movies and novels (for example Indian attacks barely ever occurred and Levi's story even shows how Native Americans could help immigrants).

|

|

|

Two of the trailers run by a great number of stations throughout the United States and Canada advertizing the 1978 mini-series, a faithful adaptation of the novel

Hans Brumbaugh, a German farmer who abandons the idea of making a living with other German immigrants in Russia, is the first to start farming the land. His attempts to hire farm hands among the successful waves of new immigrants over the decades, such as Spanish Americans and even Japanese settlers, always fail because of these the new colonists wanting to start their own independent farms and businesses. An important chapter is devoted to what can be described as no less than the genocide of Lame Beaver’s people by the U.S. Army and a troop of militiamen led by the fanatic Frank Skimmerhorn. Very much inspired by the American family of Winston Churchill's mother, the story focuses on the creation and the rise to fortune of the immense Venneford ranch, run for absentee owners in England by Seccombe an Englishman who arrived as an idealist, believing that the unspoiled nature of the West was the land of “Noble Savage” and evolved into a ruthless oligarch. John, Skimmerhorn’s son, becomes the trail boss who takes tens of thousands of Venneford cows across the great plains and helps a poor farmer’s son, Jim Lloyd, an adolescent, grow from an apprentice cowboy to future trail boss and more. Jim becomes one of the main characters of the novel and links us with the stories of his descendants and their relatives and their environment onward into the 20th century. The daily life of cowboys is also remarkably described, not forgetting that many of them were Blacks, which had almost never been mentioned previously in other novels or westerns. Centennial also describes the brutal range wars between farmers trying to protect their crops, shepherds protecting their sheep (but ruining the environment) versus the ranchers and their hired killers. The arrival of the train brings new waves immigrants and real estate speculators. Michener focuses on the crooked Wendells who will become the rich and crooked businessmen in the growing town of Centennial and the Grebbes who bought land from them for dryland farming and whose decades on the farm will be narrated until the cataclysmic Dust Bowl. How this continental disaster occurred is shown very well through the sort of microeconomic-microgeographic and environmental narration with Centennial serving as a model for not only Colorado but also for other agricultural areas of the American West. We finally meet the last of the main protagonists in the story, Paul Garrett, descendant of most of the main characters of the novel (Lame Beaver, Pasquinel, Levi Zendt, Jim Lloyd…) running candidate for the Colorado legislature (not explicitly although obviously as a Democrat, with an environmentalist agenda), losing to a Wendell (obviously a Republican) but managing to prevent the 1976 Olympic Games being held In Colorado which would have gravely impacted the natural environment. The last episode of the more than faithful television mini-series adaptation (James Michener appears in the first episode to introduce the story) ends nostalgically with Merle Haggard's song “I'd rather be in Colorado”.

James Michener’s most important contribution to literature is also a contribution to geographic culture. Centennial more than any other of his novels is not only a historic novel, it is a geographic novel, which made it unique and the first of its genre.

Michener’s fiction reflects exactly how in the 20th century history itself, as a discipline, has undergone a major reform in the way historians investigate, write, and teach about the past. Historiography is no longer about events. It is about processes. Historians are no longer interested in lining up one after the other, in chronological order, what would have been the headline news of the period they study. They analyze the elements of civilization as they evolve as slowly as slowly as landscapes, over centuries if not millennia and they identify situations that almost never change. It is a method of focusing not on fleeting events but on what changes or is permanent in the long duration--la longue durée as advocated first by Marxism and then, since the 1920s, by the French historiographic school of the Annales. This is exactly what Michener does when he describes how the landscape of Colorado evolved so slowly from the times of the formation of the earth, through the era of dinosaurs and all the way to its colonization by modern mammals and humans followed by the slow changes from hunting-gathering societies to contemporary industrial beet processing factories, the compressing of time with the introduction of railways (Levi Zendt comfortably retraces in a week the road he took months to travel with oxen in perilous conditions), and real estate speculation. When he tells us in his preamble that the Platte River behaves in his novel “as described”, i.e. without much change, we can observe continuity in the description of life along its banks between times immemorial when the two beavers dug their burrow, and the 1970s. “Only the rocks live forever” a saying of the Native Americans in the novel, is one of the major themes of Centennial. While it expresses the passing of time in the lives of the human beings it also establishes a strong sense of continuity, since the rocks (the Rocky Mountains or the buttes in the great plains) are such important features in the narrative. Just as the school of the Annales has advocated, Michener’s historic retrospective shows the interaction between evolving human societies, their cultures, mentalities, and the world views of different communities. He shows their sociology and their relation over time with the natural history of their environment, and their shaping of the human and physical geography of one area.

But just as the historians that revolutionized historiography in the 20th century were also able to focus on individuals (like Lucien Febvre’s biography of Martin Luther’s describing his personal torments and his personal motivations in creating a new religion), Michener tells us very vivid stories of characters who are representative of great historic trends and situations. This is what Tolstoy attempted in War and Peace--the first historic novel since Homer to diverge from the historic genre as presented by Walter Scott, Fenimore Cooper, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo or more recently in the Poldark series by Winston Graham, where history is only as a backdrop to the soap opera agitating the lives of the protagonists. Michener’s Lame Beaver, Clay Basket, Pasquinel, McKeague, Levi Zendt or Jim Lloyd are stereotypes, yes, but they are excellent illustrations of all the historic situations and trends, just like Natasha, Pierre or Prince Andrew and Maria, based on real persons from the generation of Tolstoy’s parents, could have been real and are excellent illustrations characterizing history in their era. Like Tolstoy’s characters, Michener’s are also interesting and lovable.

Contrary to several of his other historic novels, (or to the works of Edward Rutherford) Michener’s Centennial is not just a collection of short stories set in the same region nothing but the genealogical lines between the characters to connect the stories. Each episode introduces the next one very smooth and seamless continuation. It is why, considering all the other qualities of the novel as well, many could claim Centennial as their favorite, superior to his number one better-selling Hawaii.

Michener’s fiction reflects exactly how in the 20th century history itself, as a discipline, has undergone a major reform in the way historians investigate, write, and teach about the past. Historiography is no longer about events. It is about processes. Historians are no longer interested in lining up one after the other, in chronological order, what would have been the headline news of the period they study. They analyze the elements of civilization as they evolve as slowly as slowly as landscapes, over centuries if not millennia and they identify situations that almost never change. It is a method of focusing not on fleeting events but on what changes or is permanent in the long duration--la longue durée as advocated first by Marxism and then, since the 1920s, by the French historiographic school of the Annales. This is exactly what Michener does when he describes how the landscape of Colorado evolved so slowly from the times of the formation of the earth, through the era of dinosaurs and all the way to its colonization by modern mammals and humans followed by the slow changes from hunting-gathering societies to contemporary industrial beet processing factories, the compressing of time with the introduction of railways (Levi Zendt comfortably retraces in a week the road he took months to travel with oxen in perilous conditions), and real estate speculation. When he tells us in his preamble that the Platte River behaves in his novel “as described”, i.e. without much change, we can observe continuity in the description of life along its banks between times immemorial when the two beavers dug their burrow, and the 1970s. “Only the rocks live forever” a saying of the Native Americans in the novel, is one of the major themes of Centennial. While it expresses the passing of time in the lives of the human beings it also establishes a strong sense of continuity, since the rocks (the Rocky Mountains or the buttes in the great plains) are such important features in the narrative. Just as the school of the Annales has advocated, Michener’s historic retrospective shows the interaction between evolving human societies, their cultures, mentalities, and the world views of different communities. He shows their sociology and their relation over time with the natural history of their environment, and their shaping of the human and physical geography of one area.

But just as the historians that revolutionized historiography in the 20th century were also able to focus on individuals (like Lucien Febvre’s biography of Martin Luther’s describing his personal torments and his personal motivations in creating a new religion), Michener tells us very vivid stories of characters who are representative of great historic trends and situations. This is what Tolstoy attempted in War and Peace--the first historic novel since Homer to diverge from the historic genre as presented by Walter Scott, Fenimore Cooper, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo or more recently in the Poldark series by Winston Graham, where history is only as a backdrop to the soap opera agitating the lives of the protagonists. Michener’s Lame Beaver, Clay Basket, Pasquinel, McKeague, Levi Zendt or Jim Lloyd are stereotypes, yes, but they are excellent illustrations of all the historic situations and trends, just like Natasha, Pierre or Prince Andrew and Maria, based on real persons from the generation of Tolstoy’s parents, could have been real and are excellent illustrations characterizing history in their era. Like Tolstoy’s characters, Michener’s are also interesting and lovable.

Contrary to several of his other historic novels, (or to the works of Edward Rutherford) Michener’s Centennial is not just a collection of short stories set in the same region nothing but the genealogical lines between the characters to connect the stories. Each episode introduces the next one very smooth and seamless continuation. It is why, considering all the other qualities of the novel as well, many could claim Centennial as their favorite, superior to his number one better-selling Hawaii.

One of Michener's longest and informative interviews on his life, his work, and his views on America filmed in 1971, when the began working on Centennial

Let's face it, however, as much as creating the historic genre that will always be mitchner's landmark achievement, this Marks more the history of pop culture and educational fiction rather than great literature.

Characters draw sympathy but mostly to the historian or to the teacher. These characters are useful for the educator as are actors portraying Julius Caesar, Winston Churchill, or Malcolm X in a docudrama or a movie shown to high school students. Pasquinel, Zendt, or Jim Lloyd or after all stereotypes Without the depth of Tolstoy’s Rostovs or Pierre. Michener’s heroes, no matter how colorful and sympathetic, cannot be compared to even secondary characters such as Hugo’s Gavroche or Platon Karataev, the wise peasant soldier with a little dog being held prisoner by the French in War and Peace. These limitations in Centennial come to light when reading his other novels. They become so stereotypical, That they not only lose the educational purpose of the historic figures he invented the for Centennial, but they are as superficial as in a pulp western novel. In Alaska, they are worse than in a James Bond novel. Which then forces the demanding reader and maybe even the historian to look back at the fictional people in Centennial and wonder if mitchner could not have done better. This is particularly true for the need of Americans that he portrays.

Anthropologists have been particularly critical of Michener's competence in describing the arapahos. As many of us were expecting Michener's visit to Alaska when he was preparing a great novel about the 49th state, I had a conversation on that subject with a leading American anthropologist, Alaska University Professor Lydia Black. She had great doubts about how Alaskans would look in the new novel once it would become available. When it did, it was even worse than what was feared (it was trashed in the peer reviewed journal Alaska History but became another great bestseller ruining people's understanding of the history of Alaska). Again, this sheds a shadow over Centennial.

One of the problems in Centennial is that it completely forgets about the minorities once a chapter has been devoted to them. The Native Americans are almost completely absent from the second half of the novel, although they are the founders of the dynasty whose story is being told. The capstone story of the book is the description of Paul Garrett. It is very interesting that he is the descendant of almost all the characters in the preceding chapters, but he seems to have completely forgotten his personal connection to the most important ones, the Arapahos, except for very elusive remarks that almost sound like the “my grandmother was a Cherokee Princess” trope. So are we to conclude that Garrett, master of the Venneford ranch, is the best that all of this saga has produced and that this is a happy end because the rancher happens to be a Democrat and an environmentalist?

Finally, as in almost all his historic novels, you feel as he approaches the end, the author is becoming exhausted and wants to move on to his next project. He is in a hurry to finish and the last 100 pages read like a series of obituaries of the characters in his last chapters.

My encounter with the great man who had been one of my favorite authors was a painful experience. I greeted Michener in the museum of history and ethnography of which I was the curator and which I had help put together and inaugurate a couple of years earlier on Kodiak Island in 1985. This was a rich collection of Russian era artifacts as well as objects made by Indigenous people such as a unique 19th century Yupik kayak and numerous other objects of memory. Michener looked so bored that I began feeling embarrassed of bothering to explain to him the significance of what he did not even seem to look it. Suddenly, he woke up and with great delight rushed towards one object that attracted his interest. It was a late 19th century iron stove manufactured somewhere in the United States in the late 19th century that somehow made its way to Alaska but that had little or nothing to do with anything else on display in the museum. I tried to explain to him how Native Americans in Alaska had appropriated the Orthodox religion as have many Native Americans done with Catholicism through forms of syncretism in South America. He did not seem to listen. Two Native American students were present to express their Indigenous point of view about the exhibit and about the Russian experience of their great-grandparents and great-great- grandparents. I could not notice any eye contact between Michener and these young indigenous persons. They never got to talk because the great author never asked any questions. His mind had obviously already been made up about Alaska’s history and he knew better than us what the two centuries between 1740 and 1867 were all about.

Never meet your heroes.

However, the delightful person who accompanied him, to our museum asked very pertinent and profound questions. Something made me believe that she was the one who actually wrote much of what was in Michener’s novels... That Michener did not write everything by himself was discovered after his death as mentioned in the introduction to the 2015 edition of Centennial by Steve Berry (page xiii). Another disappointment.

Characters draw sympathy but mostly to the historian or to the teacher. These characters are useful for the educator as are actors portraying Julius Caesar, Winston Churchill, or Malcolm X in a docudrama or a movie shown to high school students. Pasquinel, Zendt, or Jim Lloyd or after all stereotypes Without the depth of Tolstoy’s Rostovs or Pierre. Michener’s heroes, no matter how colorful and sympathetic, cannot be compared to even secondary characters such as Hugo’s Gavroche or Platon Karataev, the wise peasant soldier with a little dog being held prisoner by the French in War and Peace. These limitations in Centennial come to light when reading his other novels. They become so stereotypical, That they not only lose the educational purpose of the historic figures he invented the for Centennial, but they are as superficial as in a pulp western novel. In Alaska, they are worse than in a James Bond novel. Which then forces the demanding reader and maybe even the historian to look back at the fictional people in Centennial and wonder if mitchner could not have done better. This is particularly true for the need of Americans that he portrays.

Anthropologists have been particularly critical of Michener's competence in describing the arapahos. As many of us were expecting Michener's visit to Alaska when he was preparing a great novel about the 49th state, I had a conversation on that subject with a leading American anthropologist, Alaska University Professor Lydia Black. She had great doubts about how Alaskans would look in the new novel once it would become available. When it did, it was even worse than what was feared (it was trashed in the peer reviewed journal Alaska History but became another great bestseller ruining people's understanding of the history of Alaska). Again, this sheds a shadow over Centennial.

One of the problems in Centennial is that it completely forgets about the minorities once a chapter has been devoted to them. The Native Americans are almost completely absent from the second half of the novel, although they are the founders of the dynasty whose story is being told. The capstone story of the book is the description of Paul Garrett. It is very interesting that he is the descendant of almost all the characters in the preceding chapters, but he seems to have completely forgotten his personal connection to the most important ones, the Arapahos, except for very elusive remarks that almost sound like the “my grandmother was a Cherokee Princess” trope. So are we to conclude that Garrett, master of the Venneford ranch, is the best that all of this saga has produced and that this is a happy end because the rancher happens to be a Democrat and an environmentalist?

Finally, as in almost all his historic novels, you feel as he approaches the end, the author is becoming exhausted and wants to move on to his next project. He is in a hurry to finish and the last 100 pages read like a series of obituaries of the characters in his last chapters.

My encounter with the great man who had been one of my favorite authors was a painful experience. I greeted Michener in the museum of history and ethnography of which I was the curator and which I had help put together and inaugurate a couple of years earlier on Kodiak Island in 1985. This was a rich collection of Russian era artifacts as well as objects made by Indigenous people such as a unique 19th century Yupik kayak and numerous other objects of memory. Michener looked so bored that I began feeling embarrassed of bothering to explain to him the significance of what he did not even seem to look it. Suddenly, he woke up and with great delight rushed towards one object that attracted his interest. It was a late 19th century iron stove manufactured somewhere in the United States in the late 19th century that somehow made its way to Alaska but that had little or nothing to do with anything else on display in the museum. I tried to explain to him how Native Americans in Alaska had appropriated the Orthodox religion as have many Native Americans done with Catholicism through forms of syncretism in South America. He did not seem to listen. Two Native American students were present to express their Indigenous point of view about the exhibit and about the Russian experience of their great-grandparents and great-great- grandparents. I could not notice any eye contact between Michener and these young indigenous persons. They never got to talk because the great author never asked any questions. His mind had obviously already been made up about Alaska’s history and he knew better than us what the two centuries between 1740 and 1867 were all about.

Never meet your heroes.

However, the delightful person who accompanied him, to our museum asked very pertinent and profound questions. Something made me believe that she was the one who actually wrote much of what was in Michener’s novels... That Michener did not write everything by himself was discovered after his death as mentioned in the introduction to the 2015 edition of Centennial by Steve Berry (page xiii). Another disappointment.

And yet there is still something that attracts irresistibly to Centennial. As Steve Berry wrote in that same introduction on that same page, Michener’s flaws made him human. The most touching trait of this gruffy, even rude, but remarkably generous person (he gave away an astonishing percentage of his income to educational projects) was his sincerity in celebrating how races can come together, particularly through love. All his three wives were Asians. This was not some sort of fetishism or wish for male domination over an inferior race (as very well portrayed in another great historic epic, about India, the Raj Quartet by Paul Scott), on the contrary. It was genuine, profound love for the Pacific and for the people who characterized it. I could feel this as I met with the Micheners, after a rich conversation with the delightful Mari Yoriko Sabusawa, the author’s third wife. Whether she wrote much of his fiction does not matter as much as she is one of those who very probably inspired the humanity that you do find in the novels after all.

There is much bitterness and cynicism in how James Michener developed his characters in most of his historic novels. This is not the case in Centennial. While the reader does find humanity here and there in the other novels, there is a lot of it in Centennial. Love stories, for example, are realistic and profound. Pasquino being torn between his German wife in Saint Louis, and his Arapaho wife in Colorado cannot be compared to doctor Zhivago's love for both Lara and Tonya, But it is a good story. The tragedy of Pasquinel's children is almost Shakespearean even though it falls into the trope of the “half-breed” gone rogue because they are unfit for any society— the white man's or the Natives’. Levi Zendt, having lost everything including his wife, stranded in the middle of nowhere, manages to reconstruct a life more significant than what he had hoped for in California. He becomes the founding father of Centennial and is a beacon of decency and humanity, living in harmony with the Arapahos as well as with white people sharing his values. It is an inspiring story and is not to be snubbed as if his long-lasting love with Lisette Pasquinel came out of a Hallmark TV movie. Indeed, this is the kind of person that you still find in rural America and who makes it livable despite all the rednecks (portrayed in abundance in Centennial as well in all Michener’s novels about America). One of the most touching storylines in the novel is the dispute between the two trappers, Pasquinel and McKeough. The reliable Scotsman takes care of the abandoned family of the rogue and uncontrollable Frenchman during his many absences which leads to the two becoming almost enemies. But during a fur rendezvous (a great outdoors annual market and reunion of Native American and European trappers—a beautifully described festival), Pasquinel and McKeough run into each other in their old age, and warmly reconcile after performing a silly dance to the tune of a fiddle.

Centennial is no material for Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature, but it certainly makes great stuff for lovers of the National Geographic or Outside magazine. James Michener makes you travel across breathtaking landscapes, all in your head, as if you were walking through those incredible dioramas of the New York Natural History Museum or of great IMAX documentary on American national parks. Better, it often is as if in that mess of Colorado. Mitch nurse talent is to make you truly feel as if you were feeling the summer heat of the great plains of Colorado or the extreme winter cold once they are covered with snow or when the action takes you to the Rocky Mountains nearby. When I was traveling for the first time across Colorado in September and we were hit by a blizzard, I not only remembered Michener’s explanation about that part of the American West having a climate that sometimes resembles Siberia’s, but I also saw from the great windows of my train exactly the landscape that was created in my imagination by the descriptions in Centennial. Reading Centennial you can almost feel the wind of the endless prairie blowing in your hair, smell the needles of the evergreens and hear the piercing cry of eagles soaring above the mountain tops.

There is much bitterness and cynicism in how James Michener developed his characters in most of his historic novels. This is not the case in Centennial. While the reader does find humanity here and there in the other novels, there is a lot of it in Centennial. Love stories, for example, are realistic and profound. Pasquino being torn between his German wife in Saint Louis, and his Arapaho wife in Colorado cannot be compared to doctor Zhivago's love for both Lara and Tonya, But it is a good story. The tragedy of Pasquinel's children is almost Shakespearean even though it falls into the trope of the “half-breed” gone rogue because they are unfit for any society— the white man's or the Natives’. Levi Zendt, having lost everything including his wife, stranded in the middle of nowhere, manages to reconstruct a life more significant than what he had hoped for in California. He becomes the founding father of Centennial and is a beacon of decency and humanity, living in harmony with the Arapahos as well as with white people sharing his values. It is an inspiring story and is not to be snubbed as if his long-lasting love with Lisette Pasquinel came out of a Hallmark TV movie. Indeed, this is the kind of person that you still find in rural America and who makes it livable despite all the rednecks (portrayed in abundance in Centennial as well in all Michener’s novels about America). One of the most touching storylines in the novel is the dispute between the two trappers, Pasquinel and McKeough. The reliable Scotsman takes care of the abandoned family of the rogue and uncontrollable Frenchman during his many absences which leads to the two becoming almost enemies. But during a fur rendezvous (a great outdoors annual market and reunion of Native American and European trappers—a beautifully described festival), Pasquinel and McKeough run into each other in their old age, and warmly reconcile after performing a silly dance to the tune of a fiddle.

Centennial is no material for Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature, but it certainly makes great stuff for lovers of the National Geographic or Outside magazine. James Michener makes you travel across breathtaking landscapes, all in your head, as if you were walking through those incredible dioramas of the New York Natural History Museum or of great IMAX documentary on American national parks. Better, it often is as if in that mess of Colorado. Mitch nurse talent is to make you truly feel as if you were feeling the summer heat of the great plains of Colorado or the extreme winter cold once they are covered with snow or when the action takes you to the Rocky Mountains nearby. When I was traveling for the first time across Colorado in September and we were hit by a blizzard, I not only remembered Michener’s explanation about that part of the American West having a climate that sometimes resembles Siberia’s, but I also saw from the great windows of my train exactly the landscape that was created in my imagination by the descriptions in Centennial. Reading Centennial you can almost feel the wind of the endless prairie blowing in your hair, smell the needles of the evergreens and hear the piercing cry of eagles soaring above the mountain tops.

Granted, Centennial will never be featured in the history of literature textbooks like the novels of Jane Austen, Proust, or Gabriel Garcia Marquez. As a historic novel, it is not even close to anything written by Shūsako Endō, or Marguerite Yourcenar (whom Michener admired, by the way), not to mention Gabriel García Márquez. However, if you want some intelligent entertainment, a novel about nature that is much better than an outdoorsy adventure with a New York lawyer coming to Alaska or rural New Zealand with a roll-on suitcase and high heels falling in love with a park ranger after they spend much time arguing with each other, or if you are looking for a history novel much better than the soap operas of Alexandre Dumas or John Jakes, or Jeff Shaara's Gods and Generals with its oodles of dialogue sounding like speeches, Centennial is a great novel that can be a great educational experience and make you feel like you were in the great outdoors. Thus, I can tell my students, my friends or you: read it. If you haven’t and if you make the effort to open the first page of more than the thousand in the novel, you will have great moments of pleasure ahead of you.

In Memoriam: Georges Bortoli, Jennifer Locke

It is a coincidence that on this Wednesday June 28, 2023, two anniversaries should remind us of two journalists separated by two generations. These were two television journalists, who some of us at our American University of Paris knew well. As founder and editor in chief of Nature & Cultures, a publication of the American University of Paris that has been read by over 30,000 people, I thought that it would be appropriate to commemorate both of these personalities. I had the chance to know both of them. I am indebted to the older of these two talented people to have introduced me to AUP; without this extraordinary boost to my career, I would have had the chance to known the younger one.

Today June 28th 2023, Jennifer Locke, American University of Paris alumni, would have been 40 years old. She was a brilliant student And a very pleasant personality, the kind of person who, through her participation, makes the classroom and a teacher’s career a delightful experience. I crossed her path again when she interviewed me for Fow News; By then, she had become and enthusiastic and idealistic journalist. Her career was cut short by whoever at Fox News did not realize that their channel did not deserve her talent, and then by a fatal disease at an age when life only begins.

Today June 28th 2023, Jennifer Locke, American University of Paris alumni, would have been 40 years old. She was a brilliant student And a very pleasant personality, the kind of person who, through her participation, makes the classroom and a teacher’s career a delightful experience. I crossed her path again when she interviewed me for Fow News; By then, she had become and enthusiastic and idealistic journalist. Her career was cut short by whoever at Fox News did not realize that their channel did not deserve her talent, and then by a fatal disease at an age when life only begins.

|

Today June 28th 2023 is also the 100th anniversary of the birth in Tunis of a remarkable journalist and one of the world's greatest experts on the Soviet Union and Russia: Georges Bortoli who died in 2010 at 87 in the suburbs of Paris. He knew AUP (then "American College in Paris") through his friend and colleague journalist, political analyst Pierre Salinger, former White House Press Secretary. At the end of World War II, G. Bortoli began his career in Tunis and for ten years dedicated himself to covering the problems of North Africa and the Third World. Towards the end of the 1950s, he turned to television and became, among many other activities, one of the anchormen of the sole French national broadcasting corporation (RTF) television news in Paris. In the 1960s, Georges Bortoli established himself as a specialist in the Soviet Union. He resided for several years in Moscow as a correspondent, living with his family (his delightful wife Catherine, born in the Russian diaspora in Tunisia, always full of support with her energy and sense of humor, and his children, future composer Stéphane and future scholars Anne and Catherine) for the Figaro newspaper and French television bureaus in Moscow for several years. He was subsequently an editorialist in international relations for several decades. He authored several important books on the USSR and Russia, such as The Death of Stalin (you can read the English translation) published ahead of most studies on the same subject. His Vivre à Moscou, remains one of the best witness accounts of life in the USSR in the middle of the Cold War.

Here at N&C - Nature & Cultures we wish to use this opportunity to recommend three other books that, with Bortoli’s book, we consider as the best on the subject. Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s most famous interview was conducted in dangerous clandestine conditions by correspondents Hedrick Smith and Robert Kaiser. Each of these remarkable observers of Soviet life under Brezhnev published The Russians (Smith), and Russia: the Power and the People (Kaiser). For generations, these will be primary sources to understand how the Soviet régime functioned and how Soviet citizens lived under it in the 1970s. They may last as long as Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. Nine and Jean Kehayan were French Communists when they decided to move to the USSR, the country that their ideals made them believed was the model for any society based on progress and happiness. Upon their return, tragically disillusioned, they published Rue du Prolétaire Rouge (Red Proletarian Street – where they lived in Moscow). If you can read French, this is a more recent report than Smith’s and Kaiser’s that, in retrospective, illustrates the decay of a society leading to its complete collapse only a few years after the authors released their book, causing great scandal in left-wing circles in French speaking countries.

|

Our selection for Issue No.3 :

IR Theory, Historical Analogy, and Major Power War has been recently published by our own American University of Paris Professor and prolific author Hall Gardner, former Chair of the International Comparative Politics Department.

Sara E. Davies. Containing Contagion: The Politics of Disease Outbreaks in Southeast Asia is more than relevant in this period when Asian countries' approaches to the Covid 19 pandemic has been either decried, or on the contrary presented as an example of what should have been the model for Western countries that have been overwhelmed by the situation.

But first, we wish to explain why we fell in love with the following book: (scroll down to read our other reviews)

Tricia Nuyaqik Brown & Joni Kitmiiq. Roy Corral (Photographer). Alaska Native Games and How to Play Them: Twenty-Five Ancient Contests That Never Died. University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks: 2020. ISBN-13:9781602234185 |

|

|

In his foreword to this delightful book, Nick Iligutchiak Hanson, a World Eskimo-Indian Olympics champion" writes :

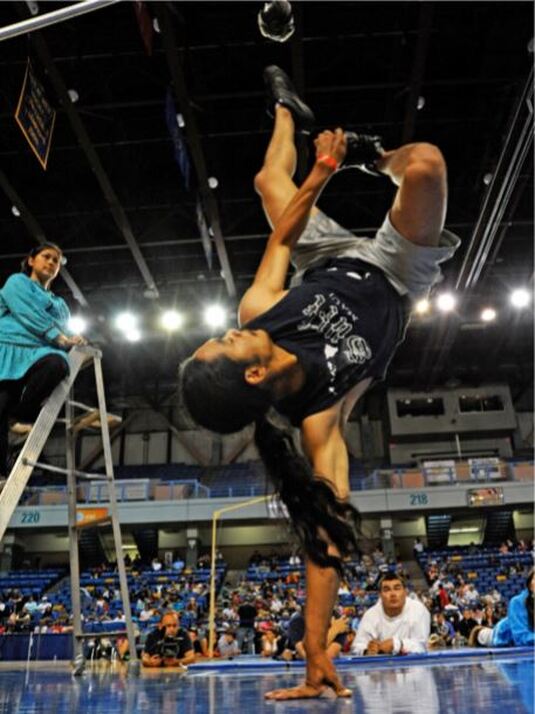

Across the country, fans of the NBC show American Ninja Warrior know me as the “Eskimo Ninja.” We Ninjas follow a demanding course that requires balance, strength, endurance, and focus, the same attributes required to play the Alaska Native Games of my ancestors: Seal Hop, Eskimo Stick Pull, Blanket Toss, and more. Our games are a bridge from the past that helps us find the best in ourselves and each other. If it weren’t for World Eskimo-Indian Olympics (WEIO) and Native Youth Olympics (NYO), I wouldn’t be where I am today. " The word "Eskimo" may immediately cause a problem in this first text appearing on page ii and therefore, needs clarification: in Alaska, the Inuits are not the only... "Eskimos". While in Canada, only the Inuit were called that name and have banned its use, the Yupik and the Inuit of Alaska, culturally and especially linguistically extremely close to eachother as well as the small group of Yuit people, have, in modern times, progressively recognized themselves as belonging to one nation: the Eskimo nation. Which is way the term is perfectly acceptable and officially used in Alaska.

As this little vocabulary precision indicates, the minute a reader opens this book, he or she is challenged with issues that open horizons far beyond those expected in a book for children or young adults. It all begins with Nick Hanson, who grew up in an indigenous village, telling us about his moving story of a Native boy whose European ancestry makes him look "White" in an almost all-Native community. He finds his identity and acceptance by practicing indigenous sports and becoming famous statewide as a champion. Nick Hanson's foreword, in just a few paragraphs, not only brings up very serious issues of identity. Because of his looks as a "white boy" little Nick was beaten up almost every day by a boy called Axel. Eventually, impressed by Nick's skills as a basketball player, Axel who, meanwhile, became the captain of the local basketball team encouraged the former victim of his abuse to practice Native Games. Axel even offered to coach Nick. Out of this experience grew a new friendship and Nick became a sports celebrity among all indigenous youths in the North West of the Americas. Later, alas, Axel committed suicide.

|

One of Nick Hanson's main motivation as an advocate for Native sports is that these activities serve as a tool for suicide prevention. But it is mainly because, as Hanson writes, it is a gateway for indigenous kids to reconnect with their own culture in a contemporary environment completely obliterated a reference to the culture of Eskimos, Aleuts or Indians (again a word Condemned by politically correct standards... White people's standards according to acclaimed native American writer Sherman Alexie who says that Indians call themselves Indians, and that "Native American" is a word made up "a liberal white man's guilt" trip).

Again, from the start, we discover a far wider picture in this publication than what is expected from a book for high school kids or in a vade mecum on sports which only seems to have been the authors' intention. Joni Kitmiiq Spiess is an Iñupiaq woman born in Nome, Alaska, who has been a traditional games competitor, and coach. After her studies in Anchorage, Joni returned to Nome and taught physical education to elementary school children from 2005–2012. She also began demonstrating the Native games to her students and coaching them in these disciplines. Back in Anchorage, she is now involved in health education for young children. Tricia Brown (now bearing the indigenous name Nuyaqik which indicates adoption by Native Alaskans), a well-known former reporter and editor of Alaska Magazine (Alaska's local equivalent of both the National Geographic and Outside Magazine), is now a freelance author who penned eight picture books for children, nearly two dozen nonfiction books for adults including the now classic Children of the Midnight Sun, which received national critical acclaim for its profiles of Alaska Native children and was, already then, illustrated by Roy Corral. Photojournalist Roy Corral, has been covered with awards in Alaska and his photography has appeared in The National Geographic, Forbes and on the walls of the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, Anchorage Museum, and the Alaska Native Heritage Center. His photographs for which epithets are superfluous illustrate almost every page of Alaska Native Games providing each of them with great visual power.

Alaskan Games and How to Play Them... is, as it's name indicates, very well detailed manual for those who wish to learn what it takes to practice sports that were created in times immemorial by indigenous Alaskans. In this book, you will get to know everything about the Alaskan High Kick, the Eskimo Stick Pull, the Greased Pole Walk the Knuckle Hop / Seal Hop (to mention only the ones with the most exciting names) and scores of others. One of the most fun, exciting and iconic of all Alaskan games (often seen on post cards, touristic brochures or in documentaries) is the blanket toss. Father Michael Oleksa, a well known anthropologist and Native rights activist,fluent in several indigenous languages and who has been living immersed in Aleut and Eskimo communities (his wife is Yupik) for more than half of a century, once explained how the blanket toss is more than it seems: it was originally believed by Europeans that soaring in the air, several feet above the ground, allowed to spot whales from afar in very flat coastal regions. "It was for te whales to see us" would very confidentially say some indigenous people to outsiders whom they trusted with their most intimate beliefs. Indeed, many indigenous populations, not only in Alaska but in other parts of the world believe that animals -- the villagers' only source of food -- come to sacrifice their own lives for which the people are eternally grateful to them. That cultural dimension is perceptible throughout the pages of Alaskan Games and How to Play Them....

This is why this how-to book for kids, is not an ordinary one. Not only have these games rarely been systematically gathered in a monograph intended for the general public and young people in particular (there exists one interesting website at the University of Alaska - Fairbanks' Alaska Native knowledge Network: Alaska Native Games: A Resource Guide by Roberta Tognetti-Stuff) "What is the human body capable of doing? If you’ve faced a life-or-death situation, you’d want to know that answer about your own body. Surviving in the wilderness—or worse, surviving when something goes wrong in the wilderness—requires physical strength and mental toughness"' write the co-autors. "Could an Iñupiaq seal hunter who is stranded on the ice jump from one floe to another? Could the Athabascan moose hunter load a hundred pounds of meat on his back and then quickly get to his feet? Could the Yup’ik fisherman’s hands maintain a strong grip after hours of pulling fish? Each of the Alaska Native games emulates real-life situations like these."

This is why this how-to book for kids, is not an ordinary one. Not only have these games rarely been systematically gathered in a monograph intended for the general public and young people in particular (there exists one interesting website at the University of Alaska - Fairbanks' Alaska Native knowledge Network: Alaska Native Games: A Resource Guide by Roberta Tognetti-Stuff) "What is the human body capable of doing? If you’ve faced a life-or-death situation, you’d want to know that answer about your own body. Surviving in the wilderness—or worse, surviving when something goes wrong in the wilderness—requires physical strength and mental toughness"' write the co-autors. "Could an Iñupiaq seal hunter who is stranded on the ice jump from one floe to another? Could the Athabascan moose hunter load a hundred pounds of meat on his back and then quickly get to his feet? Could the Yup’ik fisherman’s hands maintain a strong grip after hours of pulling fish? Each of the Alaska Native games emulates real-life situations like these."

The last pages read like a Hall of Fame on paper dedicated to the great champions of the past -- Brian Randazzo Sr. and Brian Randazzo Jr. of Anchorage, Robert "Big Bob" Aiken Jr. of Barrow, Brian Walker of Anvik and Eagle River, Reggie Joule Sr. of Kotzebue, Nicole Johnstone of Nome and Anchorage, Ben Snowball of Stebbins and Anchorage, Rod and Kyle Worl of Juneau, and Greg Nothsine of Anchorage.

We asked Trisha Brown, one of the co-authors, whether she was not worried about a potential side-effect of the book's success if it were (as we hope it would be) even greater than her classic Children of the Midnight Sun. What if the games start to be practiced by non-indigenous people in LA or Miami who would adopt these games and turn them into their own custom without ever acknowledging the games' origins, which is what has happened for example, generations ago, with the game of lacrosse. In other words, isn't there a risk of cultural appropriation? Trisha answered the following: "Non-Natives are already welcome to play them in the NYO and JNYO games. The cultural base and reason for play is already firmly documented. It's not a concern from what I can tell. One SE tribe is suing a fashion designer for appropriating their tribal symbols in clothing, but that's a different matter..."

Alaska Native Games and How to Play Them... is an inspiring book that could actually even become a life saver. This is what Nick Hanson writes in his preface: "I want kids to know that if they come from a broken home, like me . . . if they come from a community, like mine . . . if they’re going to a dark place, like I have . . . they can still stay positive. Through Alaska Native sports, I found my lifeline in physical challenges, healthy friendships, and connection to my culture. Alaska Native sports saved my life, and they still help point the way to hope."

|

The book is available for purchase at Amazon, Barnes & Noble or directly from the publisher here:

|

Don't miss Nature & Cultures' other features on the Great North: The Arctic: A New Middle East? and Renewable Energy and the Reindeer

Hall Gardner. IR Theory, Historical Analogy, and Major Power War. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. 339 pp. $84.99, ISBN 978-3-030-04635-4.

|

The originality of Hall Gardner’s most recent book (maybe the most interesting one, since he has been digesting all of its themes since his early publications as a graduate student) is to define (although implicitly rather than explicitly) what calls this being an “alternative realist”. Every argument made in the monograph is a rejection of clichés and a defense of alternative interpretation of the present conflictual situation between the USA and its allies vs. Russia, China and their allies. While criticizing the numerous preconceptions that always seemed to be the substance of realism (e.g. zero-sum game or the inevitability of war) or of liberalism (e.g. the indisputable universality of values such as human rights which risks becoming a pretext for neo-colonial military adventures presented as “crusades” for freedom), Gardner seems to attempt (not unlike Stanley Hoffmann) to reconcile what seems to be irreconcilable by focusing on the common denominator of realism and liberalism which is their potential to reduce the dangers of conflagration of devastating conflicts–--the former by seeking stability through balance of power, the latter by making peace as the ultimate standard in diplomacy.

A realist himself, Gardner nevertheless attacks some of the deep-rooted paradigms of Realpolitik. Always writing as a historian, he confronts, for example, the idea that the treaty of Westphalia established indisputable principles of state sovereignty. In his review in H-Diplo, Sarang Shidore (The University of Texas at Austin) summarized Gardner’s interpretation of the famous 1648 treaty

A realist himself, Gardner nevertheless attacks some of the deep-rooted paradigms of Realpolitik. Always writing as a historian, he confronts, for example, the idea that the treaty of Westphalia established indisputable principles of state sovereignty. In his review in H-Diplo, Sarang Shidore (The University of Texas at Austin) summarized Gardner’s interpretation of the famous 1648 treaty

|

"widely seen to have inaugurated a new era in European and world affairs, by reifying state sovereignty as a global governing principle. Westphalian sovereignty, Gardner argues, is substantially a myth. While Westphalia did put aspects of state sovereignty in place, such as the right of almost three hundred German princes to be free of the control of the Holy Roman Empire, it also limited sovereignty in important ways, for instance, by “denying the doctrine of cuius regio, eius religio (the religion of the prince becomes the religion of the state) ... established by the 1555 Peace of Augsburg” (p. 118). Rather than a strict enshrining of the principle of noninterference, Westphalia legitimized “power sharing and joint sovereignty” by giving the new powers France and Sweden the right to interfere in the affairs of the German Protestant princes (p. 117)''.

|

While accomplishing that, Gardner provides analytical criticism of such 1990s myths as Fukuyama’s “end of history” and of “liberal democratization”, and other Western normative values such as what the author calls “universal democratic moralism”, or social engineering by the US in other countries . The disillusion that came after the collapse of such utopic predictions after the wars of succession of Yugoslavia, the sinking into extreme corruption of Eltsin’s Russia and the rise of Putin (or of populist leqders in the West) could explain the excessive hostility shown to Russia today – a hostility than only fuels Putin’s own paranoia and aggressiveness. It is to be noted that Fukuyama was one of Gardner’s main critics twenty five years ago, and while Fukuyama’s “end of history” has now become a typical subject of study of typical 20th century utopian political thought, Gardner’s books from the 1990s –-- several of which are synthesized in IR Theory, Historical Analogy, and Major Power War –- have proven to have been far more accurate in their predictions about the future 21st century, neither wildly optimistic like the liberal “End of History”, nor fatalistic like “The Clash of Civilizations”.

Among Gardner’s warnings against destroying a hornet’s nest by hysterically beating on it with a stick without protection are several analyses such as this one on the Arab Spring:

Among Gardner’s warnings against destroying a hornet’s nest by hysterically beating on it with a stick without protection are several analyses such as this one on the Arab Spring:

|

Both neo-conservatives and particularly neoliberals have argued that the US and other democratic countries need to more strongly support, with greater diplomatic and financial assistance, a number of ostensi-bly universalistic socio-political movements that have begun to strug-gle against various authoritarian regimes, even if official government pronouncements in favor of those movements appears to represent an attempt to undermine the legitimacy of the regime in power. The dilemma, however, is that perceived US and foreign support for democratic movements and reforms in human rights policy within differing authoritarian countries has tended to antagonize many of those same regimes, including China, Russia, Belarus, Iran, Bahrain, Syria, while destabilizing other regimes, including Ukraine, Georgia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Tunisia, Venezuela, among others. (p. 18)

|

Subsequently, Gardner criticizes the notion of “sovereign” decision-making and polarity in the analysis of international relations and defense politics (he explains, in 11 points, that the geopolitical situations in world affairs are far more complex) and in general, all attempts by trendy contemporary analytical systems to oversimplify our grids of interpretation. He says for example, that

|

Contrary to the neorealist stereotype, states do not always interact with other centers of power and influence (states, inter-governmental actors and differing non-state, alt-state, and anti-state actors) in conditions of perpetual conflict or in circumstances of extreme tension in all cases. It may be true that the “post-bipolar” global system has attempted to stabilize itself through oligarchical cooperation in the Group of 7 (G-7) or Group of 8 (G-8 when Russia is included) and Group of 20 relationship to the dangerous exclusion of the Group of 77 But the same hegemonic and opposing states have also sought near universal cooperation in the 2015 UN COP-21 Climate Change Conference—that is, until the hegemonic US, under the Trump administration, opted to drop out. (p. 55)

|

He proposes instead to consider the soundness of a concept of “highly uneven polycentrism”.

The mainstream press journalists and sometimes even academics often label the present tensions between the US and its allies and Russia or China as a “Cold War II”. Gardner’s monograph is the first to systematically explain why the analogy is “not entirely relevant to today’s circumstances even if there are some similarities” as he explains in his introduction. Numerous arguments are listed to support an alternative view : the present situation resemble just one of the periods preceding a great conflict–World War I or World War II–or the Cold War, but resembles all of them at the same time. Which is the foundation of his concept of "alternative realism", the central theme of this book.

According to Sarang Shidore, whose review of Gardner's IA... is otherwise rather positive, this is the books main weakness. He writes the following:

The mainstream press journalists and sometimes even academics often label the present tensions between the US and its allies and Russia or China as a “Cold War II”. Gardner’s monograph is the first to systematically explain why the analogy is “not entirely relevant to today’s circumstances even if there are some similarities” as he explains in his introduction. Numerous arguments are listed to support an alternative view : the present situation resemble just one of the periods preceding a great conflict–World War I or World War II–or the Cold War, but resembles all of them at the same time. Which is the foundation of his concept of "alternative realism", the central theme of this book.

According to Sarang Shidore, whose review of Gardner's IA... is otherwise rather positive, this is the books main weakness. He writes the following:

|

Gardner even proposes some grand bargains that such contact groups could arrive at. For Ukraine, this means recognition of Russian sovereignty over Crimea but with Russian compensation paid to Kiev, a free-trade arrangement with Europe and the United States to give them a deep role in Crimea’s economy, and a pathway to future shared sovereignty over the annexed territory. A similar joint sovereignty approach is recommended to resolve the multi-stakeholder South China Sea dispute. A contact group could also resolve the Syria dispute with a resultant coalition government comprising all Syrian combatants, including the current members of the Bashar al-Assad government, and the Yemen war with the Omani proposal as a starting point.

How could these grand bargains come about? This is where Gardner starts to slip. He claims this approach will work on the parties’ realization “that political, economic, and technological cooperation will most likely bring benefits for all sides in the long term than perpetual conflict” (p. 110). The problem with this assumption is not that long-term win-wins do not rationally exist (they often do), but rather that in a time of acrimony, nationalism, and tendencies toward greater authoritarianism on all sides, such rationality could well be overwhelmed by other more potent rationalities of short-term aggrandizement and saving face. Though the idea of an informal contact group has its advantages, Gardner’s argument that a change of diplomatic format would do the trick is less than credible. The Ukraine dispute, for example, has degenerated into bitter acrimony on both sides with an ongoing hot conflict. This is the case notwithstanding the work of the Trilateral Contact Group—precisely the sort of approach that Gardner recommends. But walking back from the mutual US-Russian antagonism will likely take more than the right negotiating format. There first must be a will to meet the adversary part of the way—a difficult challenge to overcome when the conflict is portrayed in starkly moralistic terms, particularly on the side of Washington. Gardner has no convincing practical proposition that addresses this challenge. It is in his inability to adequately define his theoretical concept of “alternative realism,” however, where Gardner truly falls short. Alternative realism seems to be defined more by what it is not than what it is. Time and again (and convincingly on many occasions), Gardner rebuts many cherished axioms of neorealism. This includes the assurance of nuclear deterrence, state sovereignty, the concepts of polarity and balance of power, unitary states, and anarchy.[4] Alternative realism is equated with a constructivist critique of Hans Morgenthau and preventive diplomacy. William Fulbright’s quote “morality of decent instincts tempered by the knowledge of human imperfections” is also depicted as a guiding principle (p. 20). Later in the text, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev is held up as a practitioner of alternative realism, with his revolutionary contributions to ending the Cold War, while at the same time developing good relations with China as a hedge against NATO. There is also a reference to alternative realism as a “critical comparative historical approach” (p. 26). All this, though useful, does not amount to a coherent theory with with clear and testable principles and demonstrated explanatory (far less predictive) power. The elements that seem to constitute Gardner’s alternative realism—the centrality of historical influences, polycentrism as representing the world order, the importance of non-state actors, absolute gains trumping relative gains, and the promise of informal diplomacy—appear to come more out of various well-trod pathways of liberal and constructivist thinking than any brand new theoretical approach. But the reader is left even more confused at one point by an extensive taxonomy of states centered on space and power, apparently drawn from theoretician George Liska, which bears more than a passing resemblance to the early twentieth-century framework of geopolitics. Is “alternative realism” then simply a smorgasbord of various international relations frameworks, excluding neorealism? The reader is never provided a clear answer. |

Asked to respond to this criticism, Gardner sent N&C - Nature and Culture reviewers the following text:

|

Sarang Shidore has argued that the concept of “Alternative realism seems to be defined more by what it is not than what it is.” Yet this argument misses the point that alternative realism does clearly define priorities in terms of national interests---but with a broader conception of that "national interest" than that of neo-realism and traditional realism.

The first priority of alternative realism is to avoid situations that would draw a state and its population into major power wars or into interminable wars with no clearly defined goals or objectives. While powerful interest groups and factions may possess personal interests in engaging in destructive conflicts, the state and society as a whole rarely possess a strong interest in engaging in such conflicts. And rarely do the opposing states and societies. Even if one side believes it can “win” such a conflict, the human suffering and direct and indirect costs can be enormous. So-called winners could turn out to be losers in the long term. Alternative realism recognizes this dilemma and argues that the power of such groups and factions that push for war must be challenged and neutralized---if possible---in order to prevent even deeper domestic social and political conflict that could also widen and intensify. One of the major reasons for placing major powers with conflicting interests on the UN Security Council is to sustain a dialogue between those rivals. Such a dialogue is intended to prevent either direct conflict or proxy wars between those rivals. Traditional realists, such as Henry Kissinger, may have been more tolerant of so-called “limited” wars, but only so long as "limited" wars did not provoke major power wars. But even those so-called “limited” wars do not serve the general interests of the state and population if they become costly, interminable, and destructive to national morale---much as Hans Morgenthau, in opposition to Kissinger, argued in response to the brutal American conduct in the Vietnam war. Surprising many, Morgenthau, as an alternative realist, opposed the Vietnam war. This brings me to the concept of Contact Group diplomacy which is designed to help transform if not resolve both major and regional power conflicts (and so-called "limited" conflicts) by incorporating into discussions as many states (and third actors such as NGOs and anti-state movements) that are concerned with such a conflict or dispute as is possible and practical. In criticizing my concept of Contact Groups, Sarang Shidore argues, “Though the idea of an informal contact group has its advantages, Gardner’s argument that a change of diplomatic format would do the trick is less than credible. The Ukraine dispute, for example, has degenerated into bitter acrimony on both sides with an ongoing hot conflict. This is the case not withstanding the work of the Trilateral Contact Group—precisely the sort of approach that Gardner recommends.” But this is not the case: I do not recommend the Trilateral Contact Group as a final step in the negotiation process as Shidore argues that I might. The Trilateral Contact Group (which involves Ukraine, the Russian Federation, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe) can only represent a first step in a concerted negotiation/ conflict transformation process. The Trilateral Contact Group by itself will not succeed if it is not soon followed up by American and NATO participation leading to a rapprochement with Moscow. As I argue in World War Trump (Prometheus Books 2018) and in IR Theory, Historical Analogy, and Major Power War (Palgrave Macmillan 2019), the conflict in eastern Ukraine and over the Crimea will not be transformed toward less conflictual situation until Washington—in working with NATO and the European Union— resolves to engage in full-fledged diplomacy with Moscow that is designed to forge a general entente between the US, EU and Russia over a neutral Ukraine, among other issues to be negotiated As I argued in IR Theory, Historical Analogy, and Major Power War, such an alternative realist position may have failed to have established a major power entente between Britain, France and Germany (that did not concurrently thoroughly alienate Russia/ Soviet Union) before both World War I and World War II—but this historical analogy does not necessarily mean the quest for a general entente relationship between the US, European Union and Russia (that will not concurrently alienate China) will fail in contemporary circumstances. What is needed is effective leadership with foresight that is willing to sustain negotiations in the long term despite the domestic and international hurdles that such leadership will face in seeking such a major power entente. Whether such a leadership that is willing to engage in a truly peace-oriented strategy will come to power in the United States given domestic circumstances remains another question. But that is not the fault of alternative realism! |

The best is now to let readers decide on the merits of this defense of "alternative realism". Whether said readers will remain skeptical or be convinced, it is a good mental exercise which should be one more reason to purchase the book.

Another quality is Gardner’s constant historic approach (going all the way back to the 17th and even 16th century) in his discussion of such theoretical problems in the domain of political science theory only underline how relevant is the discipline of history. It is an implicit argument that is also recurrent throughout the text.

Many will object to the somewhat normative nature of IR Theory, Historical Analogy, and Major Power War for being. But given the dangerous circumstances we are in, why not defend such norms as diplomacy and peace as opposed to let the situation degenerate into World War III.

Finally, those who know Gardner's books very well (for example Lee Huebner, George Washington University, former International Herald Tribune boss or Robert Jackson of Carleton University, Canada, who both favorably reviewed this last opus) have witnessed over the years how the author’s style has evolved from extremely lengthy convoluted sentences to limpid prose that is easily and immediately understandable, while surrendering nothing to the ambition of conveying extremely complex subject matters and theoretical analysis.

Sara E. Davies. Containing Contagion: The Politics of Disease Outbreaks in Southeast Asia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. 224 pp. $54.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-4214-2739-3.

Reviewed by Eva Hilberg (Hebrew University of Jerusalem/ University of Sussex)

Originally published on H-Diplo (March, 2020) Commissioned by Seth Offenbach (Bronx Community College, The City University of New York)

In a time that increasingly questions the efficacy of diplomacy and multilateral treaties, Sara E. Davies’s most recent work serves as a well-researched reminder of the transformative potential that can reside in the making of agreements and in the creation of diplomatic structures between regional partners. Containing Contagion focuses on the politics of disease outbreaks in Southeast Asia, where recent epidemic outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and H5N1 (avian influenza or “bird flu”) created a strong political will for cooperation in response to public health emergencies—which by their very nature do not respect boundaries and thus are truly transnational. Against the backdrop of the simultaneous implementation of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Health Regulations (IHR, revised in 2005), this book explores the different ways this cooperation was institutionalized and made to work in Southeast Asia, all the while asking the core question of whether diplomacy can actually make a measurable difference—and if so, why and how? This question goes to the heart of the study of international relations, and this book is a valuable contribution not only to the study of global health diplomacy but also to wider discussions within this field.Challenging the prevailing perception of a general failure of IHR implementation, this book presents a meticulously researched reevaluation of state performance with regard to the eight core capacities enshrined in the revised IHR. This account is contextualized with different layers of institutional international organizations that are region specific to Southeast Asia—including the two WHO regional offices that cover this geographical area, Western Pacific Regional Office (WPRO) and South-East Asia Regional Office (SEARO); the preexisting Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); the extended ASEAN Plus Three (including Japan, China, and South Korea); the regional Mekong Basin Disease Surveillance (MBDS) network; and the unique organization specifically created for the implementation of the IHR in Southeast Asia, the Asian Pacific Strategy for Emerging Infectious Diseases (APSED). The region’s combination of technical and political institutions in the field of disease diplomacy is particularly notable as Southeast Asia is known for its long-standing commitment to the principle of noninterference, making the implementation of the IHR an unusual case in which states “acquiesce to an international regulation coupled with a framework that permitted evaluations, even interference and judgment, from an international organization, the WHO” (p. 4). Davies argues that what emerges from this “curious case” of collaboration in a noninterference environment is an empirical account of “compliance pull” through informal processes (p. 8).