|

Ce site Web utilise des technologies de marketing et de suivi. Si vous ne les acceptez pas, tous les témoins seront désactivés, sauf ceux qui sont nécessaires au fonctionnement du site Web. Veuillez noter que certains produits pourraient ne pas fonctionner aussi bien sans les cookies de suivi. Refuser les cookies |

Texts, photographs, links and any other content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.

|

Nature & Cultures, the American University of Paris geographic magazine for global explorers, No. 8

Continued from Issue No 7.

As soon as a Ukrainian intellectual would begin to affirm the importance of Ukrainian culture and the originality of its language, literature, and history, that person would be seen immediately as suspicious by too many Russians. Whatever was originally Ukrainian and different from Russian culture is still perceived today by a great number of Russians, including academics and highly educated people, as something foreign, as something imported and artificially imposed by the Polish-Lithuanian régime. Speaking Russian, identifying as Russians and assimilating Russian culture in the representations of Ukraine in the mental maps of probably a majority of Russians would be how Ukrainians would return to their original conditions as inhabitants of ancient Rus’. Ukrainian ultra nationalism reverses this representation by attempting to present anything Russian as Asian, with the idea that the Mongol-Tatar rule of almost three centuries completely obliterated anything Slavic and anything that Russians might have had in common with Ukrainians. In this view, Ukrainians had the chance of escaping Mongol-Tatar rule when they were under the authority of Lithuania and Poland (this conveniently omits several decades of Mongol presence in the 13th and 14th centuries and the fact that Crimea was almost entirely inhabited by Tatars until late in the 18th century).

THE PRESSURES AGAINST UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE UNDER TSARISM

To be fair to Russians, a few simple comparisons must be made. In Brittany or other non-French speaking provinces in France, in Ireland, Wales for Scotland, and in Indian reservations in the United states, washing school children’s mouths with soap as a punishment for speaking their native tongue was one of the common practices illustrating the efforts of great Western powers to eradicate local languages. Nothing of the sort that was frequent in the educational institutions of the Russian empire. While Brittany’s native language had become all but extinct in by the end of the 20th century (the Breton spoken today by most is a second language reintroduced by a school system reformed in the late 1970s and 1980s) and less than 2% of the Irish spoke their native tongue in 2016 on a daily basis (only 39.8% claimed being able to use it) while 81% of Ukrainians use Ukrainian on a daily basis. True, all of these Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians (except for maybe a few individuals with barely any education living in extremely remote rural areas), speak Russian. Bilingualism had always been a reality.

The Linguistic Battle

Until the 1820s, there had never been among Russians and Ukrainians any profound theoretical debate over ethnic identity and language, nor about the importance of either Russian or Ukrainian cultures. The elites spoke French among themselves and constituted a great mixture of Slavic, Germanic, and other origins. What defined identity in Russian imperial society from Peter the Great to the Romantic period was to identify with the social cast to which one belonged--the nobility, the merchant class and it's various guilds, the clergy, the urban and suburban commoners and artisans plus their own professional associations, and the vast majority who were either free or indentured peasants all organized by village in tightly knit collective structures such as the mir. The many ranks in the civil service and the military hierarchy overlapped these social units. This is where each individual, Russian, Ukrainian, or any other subject of the tsar represented themselves: they belonged first to a household, then to a village or suburb or city street, to a caste, and eventually, to a professional guild or to a rank in the armed forces or in the civil service. Orthodox Christians saw themselves above all as Christians; contrary to Farnce or England, where the words “peasant” and “paysan” come from the Latin pagus (country) and paganus (pagan), rural villagers were called “krestyane” (christiani)--Christians. A Russian identity or Ukrainian identity were almost absent from collective social representations.

When the educational system of the empire began growing, Russian as well as the local language was used and promoted in Church services, in parish schools, in seminaries (which served as the secondary educational institutions), and in higher education. The university of Kazan became specialized in the study of the Asian languages of the empire. |

As the idea of nation-state was rising throughout Europe, and since Russia's Empire was all but a nation (were the 90% of its inhabitants that we're illiterate peasants even aware of the multitudes that inhabited lands beyond their own province?) high-ranking government officials and intellectuals like the visionary statesman Speransky (strongly influenced by freemasonry) and, although the clergy disliked Speransky, inspired clerics (most of whom had been missionaries and the remote territories of the empire such as Innocent Veniaminov, future Metropolitan of Moscow), attempted to create a common unitary representation of the Empire by promoting a policy of cultural diversity, a synthesis of Russian and local non-Russian culture--not a “melting pot”, but a mosaic. For the members of the clergy driving this policy, the Orthodox Church was to be the cement between Russian and indigenous cultures.

Bilingualism was systematically practiced. When the educational system of the empire began growing, Russian as well as the local language was used and promoted in Church services, in parish schools, in seminaries (which served as the secondary educational institutions), and in higher education. |

The Aleuts were among the first to have an alphabet transcribing their indigenous tongue as developped by tribal chiefs and missionaries working together which allowed the first schools, emerging in the Aleutians in the 1820s, to offer lessons in Russian and in Aleut. Not only was there no demand by missionaries to abandon local customs, these were permitted and sometimes even encouraged, contrary to what was seen in other missionary colonial environments in Africa, in the Americas, or in Asia.

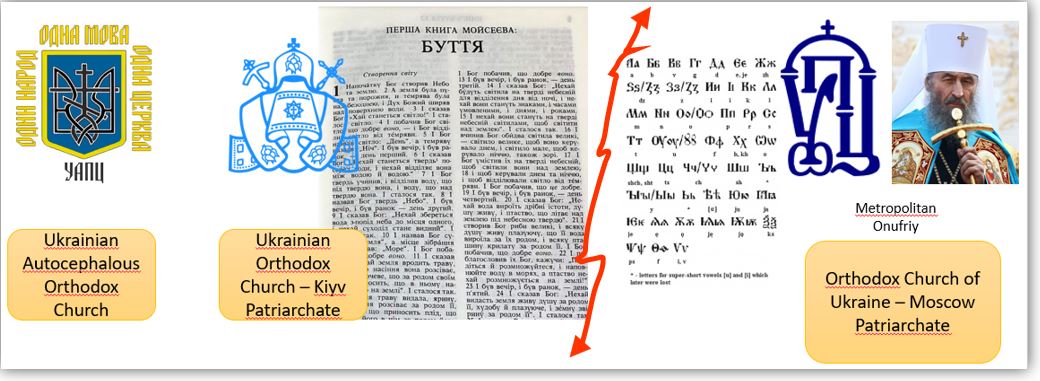

Wanting to worship in modern Ukrainian is a reason why, since 1991, millions of Ukrainian Orthodox believers have been drawn to Orthodox splinter groups refusing the authority of the Moscow patriarchate. While the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (the "OCU", a semi-autonomous division of the Moscow Patriarchate) still uses Church Slavonic as a liturgical language (as does the Russian Orthodox Church), the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (the "UOC", recognized by approximately half of the Orthodox Churches in the World as autocephalous, i.e. a fully independent self-governing assembly of bishops). A third splinter group the not recognized by any other Orthodox Church) was the first to switch to modern Ukrainian in the 1990s. (See part 3 of our series on Ukraine in the July 2024 issue No. 9 of Nature & Cultures -

There was one major defect in this policy of diversity: Ukrainians were excluded from it. While, Aleuts, Yakuts, the Finno-Ugrian Komi and scores of other ethnic groups could enjoy Orthodox services in their own tongue, the civil authorities and most religious authorities (not all) imposed the old Church-Slavonic too be the exclusive liturgical language in in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus[1], forced Orthodox services to exclusively. Ukrainians and Belarusians were supposed to be Russians and not pretend to be some indigenous tribe different from the Russian population. Moreover, to this day, the Moscow Patriarchate insists on banning modern Russian, Belarusian or Ukrainian from liturgical practice, as if Slavonic was some sort of special sacred language… which goes against the very reason Saints Cyril and Methodius translated sacred texts into that same language! It is a cause of divisions in the Orthodox Church in today’s Ukraine; wanting to worship in modern Ukrainian is a reason why, since 1991, millions of Ukrainian Orthodox believers have been drawn to Orthodox splinter groups refusing the authority of the Moscow patriarchate. More on that later (see part 3 of this series on Ukraine and Russia in the next issue of N&C). Back to the second half of 19th century and early 1900s.

In the first half of the 19th Century, the French revolutionary representations of the nation-state, the growing success of the American experience (an empire made of a patchwork of Europeans colonizing native tribes while representing itself a nation), and finally, an emerging German school of geographers who developed a powerful essentialist representation of each state as a cohesive, yet territorially expanding nation, all gave birth to a quest for a Russian identity. Was Russia an Empire or a nation? Was it European or Asian? Were Russian civilized or (according to both Western European aristocratic or bourgeois representations, as well as Karl Marx) backward barbarians? How to reconcile all the contradictory answers to these and other questions about Russian identity? At first, the representation of a multicultural diverse mosaic was seen as the ideal solution.

At the same time, because of the same cultural influences, similar questions about identity arose among the Ukrainian-speaking urban educated elites. There was a twist to it. Are Ukraine and Russia the same nation? And if Russians are Asians and barbarians, were Ukrainians not different? Were they not European and civilized? A head-on collision between Russian and Ukrainian nationalism was now inevitable as both ideologies were maturing.

At the same time, because of the same cultural influences, similar questions about identity arose among the Ukrainian-speaking urban educated elites. There was a twist to it. Are Ukraine and Russia the same nation? And if Russians are Asians and barbarians, were Ukrainians not different? Were they not European and civilized? A head-on collision between Russian and Ukrainian nationalism was now inevitable as both ideologies were maturing.

"Farewell Europe" painted in 1894, represents Polish insurgents being escorted under guard by Russian troops to Siberia after the failed Polish uprising of 1863-1864. Part of one of these convoys, Polish artist Aleksander Sochaczewski included himself in this group portrait. Prisoners were identified by having half of their head shaven and a red rhombus (the infamous "Ace of diamonds") sewn on their back. The obelisk marks the border between Europe and Asia.The "January Uprising", as this second Polish war of independence was called, infuriated Russian conservative nationalists and gave them an advantage over tsarist statesmen, church leaders and intellectuals who considered that cultural diversity should a foundation of the Russian Empire's social structure. The policies of russification would soon be imposed upon all non-Russian populations, grave consequences for Ukrainian cultural expression.

|

A demonstrator with false stitches painted on her mouth is holding an imitation of the Valuev Circular that called, in 1863, for a ban on the Ukrainian language in most publications (except for a limited number of novels and poems). The demonstrator in imperial uniform is disguised as administrator Piotr Valuev. The demonstration took place in the Ukrainian capital in 2015 at a time of tensions between Ukrainians whose maternal tongue is Russian (the majority in Kyiv, Odessa and the Easternmost parts of the country) and Ukrainians whose maternal tongue is Ukrainian. A minority of Ukrainians also speak Surzhik, a dialect comparable to a pidgin combining Russian and Ukrainian.

Photo. by Vidsich |

Preceded by a first Polish uprising in 1830, the January Uprising of 1863-1864, a Polish war of independence from Russia, influenced the last years of tsar Alexander II, and especially the reigns of his successors, the last two emperors, Alexander III and Nicolas II. A policy of russification replaced the cultural policy of diversity. The harsh measures against Ukrainian culture, so intimately associated with Polish culture, were announced in July 1863 (only a few months after the January Uprising) by the infamous Valuev Circular. This was a directive signed by Interior Minister Piotr Aleksandrovich Valuev sent to the Kiev, Moscow and St. Petersburg censorship committees, forbidding to print any religious or educational material in Ukrainian. Only pure literature--prose or poetry--was allowed. The document is infamous for having stated that “no special Little Russian language, ever was, is and will ever be”. Calling Ukrainian (“Little Russian”), a dialect, Valuev affirmed that “used by plain folk, [it] is the same Russian language, only spoiled by the influence of Poland”. Let us once again be fair to Russians. While the measure favored by Valuev was supported by the press in Moscow it was strongly criticized in the press in Saint Petersburg and by no other than the Minister of Education Golovnin and one of the leaders of the Slavophile movement, Ivan Aksakov who also defended the “Ukrainophiles” targeted by Valuev. But in May, 1876, Emperor Alexander II, in the German city of Bad-Ems, signed what entered history as the “Ems ukaz” (executive order of Ems), a ban on the use of Ukrainian in teaching, issuing documents, composing music and pronouncing church sermons. The decree also prohibited both printing in Ukrainian on the territory of the empire and the import of books printed in Ukrainian, as well as the production of Ukrainian-language theatrical performances and concerts.

|

The REVOLUTION AND THE SOVIET STATE

The internationalist ideology of the Bolsheviks and of their Marxist allies should have been a relief against Russian nationalistic domination. To be fair, modern Ukraine owes a great deal to the Soviet state for the size of its territory, and the resilience of its language and culture. Indeed, the rights of minorities, particularly their cultural rights, like the right to use their own language in public and in government institutions, was a promise that most Bolsheviks sincerely wished to implement. The key word here is most Bolsheviks. Their promise was kept, but only for a few years. The Soviet régime also brought a trail of misery. Even genocide.

The first modern Ukrainian state… or states?

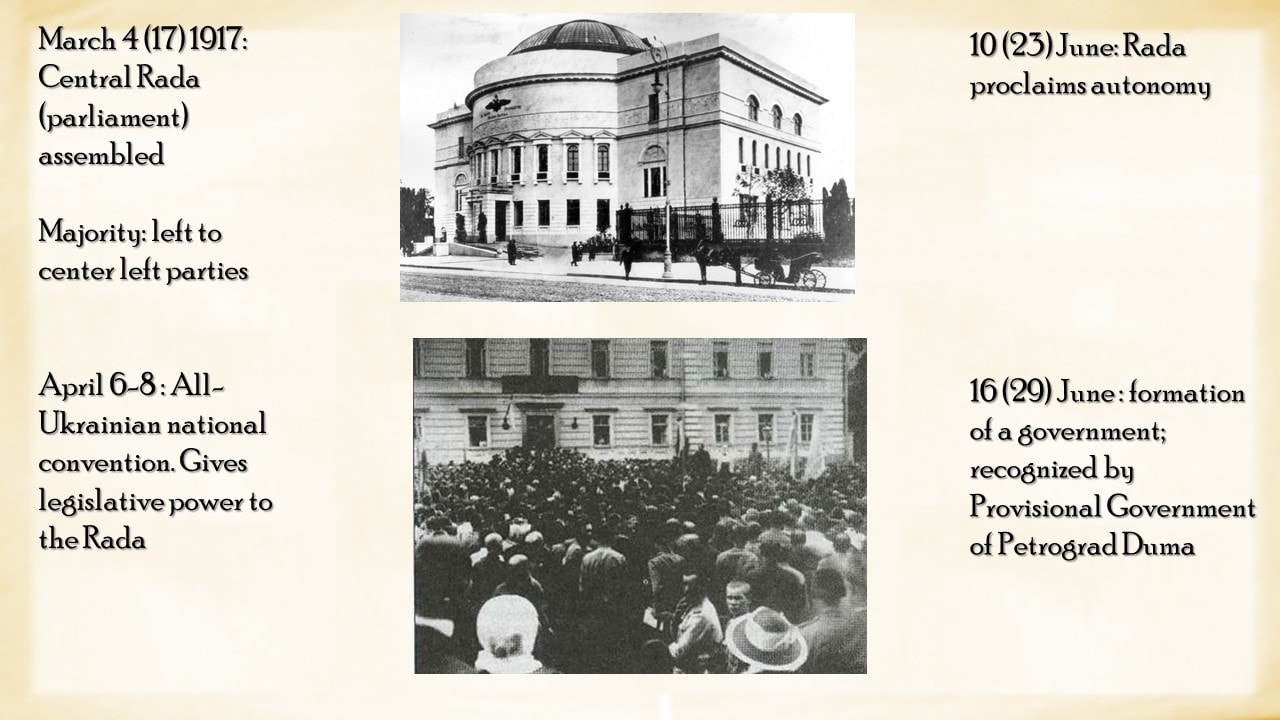

In 1917, the provisional government that transformed the Russian empire into a Republic after its February revolution already began delegating sovereignty to Ukraine in the form of Russian army units being designated as specifically Ukrainian regiments. But most of Ukraine was under German occupation at the time. The first attempt to create a modern Ukrainian independent state was the Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic. In March 1917, a National Congress in Kyiv elected a Central Council of Ukraine, which had been composed o

The Ukrainian State (Ukrainian: Українська Держава, romanized: Ukrainska Derzhava), sometimes also called the Second Hetmanate (Skoropadsky)

The internationalist ideology of the Bolsheviks and of their Marxist allies should have been a relief against Russian nationalistic domination. To be fair, modern Ukraine owes a great deal to the Soviet state for the size of its territory, and the resilience of its language and culture. Indeed, the rights of minorities, particularly their cultural rights, like the right to use their own language in public and in government institutions, was a promise that most Bolsheviks sincerely wished to implement. The key word here is most Bolsheviks. Their promise was kept, but only for a few years. The Soviet régime also brought a trail of misery. Even genocide.

The first modern Ukrainian state… or states?

In 1917, the provisional government that transformed the Russian empire into a Republic after its February revolution already began delegating sovereignty to Ukraine in the form of Russian army units being designated as specifically Ukrainian regiments. But most of Ukraine was under German occupation at the time. The first attempt to create a modern Ukrainian independent state was the Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic. In March 1917, a National Congress in Kyiv elected a Central Council of Ukraine, which had been composed o

The Ukrainian State (Ukrainian: Українська Держава, romanized: Ukrainska Derzhava), sometimes also called the Second Hetmanate (Skoropadsky)

The government, faced with having to manage an increasingly diverse human geography as the territory of the Empire expanded, having become the largest state in the world, began conceiving russification as the ultimate solution for all the ethnic groups under its authority. But too much had already been allowed before the 1860s and too much had been published before the Ems order to stop the spread of books and periodicals that had already been published in Ukrainian before the ban.

The policy of russification only created frustration and anger among non-Russian populations that may have been one of the main factors, if not the main factor, outside of European Russia, for the fall of the Empire in 1917.

The policy of russification only created frustration and anger among non-Russian populations that may have been one of the main factors, if not the main factor, outside of European Russia, for the fall of the Empire in 1917.

The two leaders of the main factions fighting for power in the newly independent Ukraine: the anti-Russian, anti-Bolshevik populist nationalist Semion Petliura (on the left, with Polish General Pilsudski - with mustache on his right) and the radical anarchist Makhno (on the right) who allied with the Bolsheviks who would later brutally eliminate him and his followers.

The territory of Ukraine was augmented thanks to the Soviet government (which Putin’s propaganda points out insistently). First, in the 1920s the South eastern periphery, pretty much the regions of Donbass and Lugansk we're the fighting is happening presently, then parts of what should be in Moldova today but it's still in Ukraine and in 1939, when Stalin invaded Poland at the same time as Hitler, the territories lost by the poles went to Belarus and Ukraine. Finally, in 1954, all of Crimea was annexed to Ukraine during the celebrations of the Treaty of 1654 that separated the Cossack siege to Muscovy. Then general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev was the first Ukrainian to serve in that position; He was followed by another Ukrainian, Brezhnev, succeeded why Andropov, himself succeeded by a third Ukrainian, Chernenko. Traffic was from Russian lands, further east from Ukraine and further east from the dawn, almost in the Caucasus, but his heavy Ukrainian accent revealed the origins of his ancestors who had settled that region. The impression, however, that Ukrainians received a special treatment under the Soviet regime because of internationalism and because of the promise by the Bolsheviks to get rid of Russian nationalism and give the nationalities equal rights would be a very false impression. From the very beginning Xenia had difficulty implementing these principles.

While the Bolsheviks indeed tried to break the back of Russian nationalism, promoted local languages and literature as well as local cultures, from which Ukrainian language and culture benefited in a way that Ukraine as we know it today would not be enjoying its language and culture as it does, also fought, at the same time, anything that could be suspected of being narrowly nationalistic and therefore contrary to internationalism. Lenin understood the problem seemed powerless to correct it. Quote from Lenin. Many Ukrainians perceived the advance on their territory of the Red Army pursuing the white army as an invasion. Quote by Olga But it could be even worse. Many Ukrainians perceived of themselves, because they were either related to cossacks or were influenced by their cultures, as a people they have developed social values such as freedom, and entrepreneurship. At the time of the revolution the first sociological research that have been conducted concluded that commitment to religion was stronger in several regions of Ukraine than it was in most parts of Russia. Results of the vote of 1918. Also, it is in Ukraine that the white army found most of its recruits. In the fall of 1920 when the Red Army had reached the Black Sea, despite promises of amnesty by frozen if white army personnel that could not be evacuated to Turkey or Yugoslavia surrendered their executions were carried out. For the Cossacks it can be described as a genocide. 10 years later, the worst episode in Ukrainian history the holodomor, a plan of artificial famine, carried out by the Soviet government wiped out 3 million inhabitants. Stalin, who had been warned by legion, considered that it was easier to govern a country of 10s of millions with dozens of different languages and cultures by imposing this standardized culture and language for all. A Georgian, he had no particular attachment to Russian, which he spoke with a heavy foreign accent, but it was more practical 2 user the language of the majority of the inhabitants of the USSR. “teachers from Russia or other Republic who were appointed to our schools and universities in Ukraine would always make fun of our language, of our Ukrainian accent when we spoke Russian and generally considered us as yokels”, said my friend Olga M.

While Ukraine became a sovereign nation in 1991, it had great difficulty establishing economic and political independence from Russia. Being the size of the continent, with countless known or untapped natural resources, especially oil and gas, Russia was able to rebuild an economy after the collapse of all social and economic structures of the Soviet Union, much faster than Ukraine the main resources of which are cool (in diminishing demand in the West) and agricultural products. When I decided Ukraine then 20 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, I felt as if I had gone back 20 years in time and was back in Russia 10 or 20 years earlier under Yeltsin. The country seemed poor, shabby, and chaotic. By then Russia, at least and it's great urban centers and at least the appearances of an average American city (every time I return to the United states I find that the country it's beginning to look more shabby and poor). Unequal levels of income for the country and for the population rapidly became an opportunity for Russia. Russian businessmen could import agricultural products and cool profiting from cheap Ukrainian labor. For a long time, the Kremlin could control those sile political leaders give through old party networks. And with Ukraine's complete dependence on Russian oil and gas. But the population could see how all the populations of central and Eastern Europe that had once been under communism word evolving to the point where you could no longer distinguish their lifestyles from those of western Europeans while Russia was still far behind and was holding back Belarus and Ukraine even further behind. What Russians have trouble understanding is that the new opportunities that arose dash exploitation of agricultural lands not 4 humans but 4 the western need to feed cattle for its ever growing meat industry, both activities of which are completely incompatible with of the type of agriculture and mining that the Russians wanted to exploit and investing less than their western competitors dash did not just open New Horizons 2 opposition leaders (damn that that democracy that still made Ukrainian politics complicated and unpredictable) but it also gave hope, no matter how utopian, to the masses of Ukrainian citizens question losing all of the benefits they had under the Soviet Union had not gained much under Russian controlled capitalism parenthesis medical care, for example, must be paid for just like in the United states). First came the orange revolution, then came the Maidan revolution less than a decade later. Russians only saw this as a result of the Great Game played by the United States and its western allies constantly pushing their luck while constantly seducing Central and Eastern European countries to join NATO or the European Union, presenting Russia as the epitome of all evils (as if Saudi Arabia, the interests of which are defended by the United states in the Middle East, was the Valuev model of democracy). What Russians fail to see is that the common denominators that they have with Ukrainians--the common origin of their states, the common religion, languages that are very close to each other, millions of families with close kinship, common socialist ideas for those who still believed in the positive aspects of the Soviet system (one of the best educational systems in the world, spectacular achievements in the arts and science, solidarity with the Third World and exploited workers, etc.)--were just not enough to outweigh the European dream that suddenly rose on the horizon for millions of Ukrainians who thought they could soon travel to Paris and work in France with no restrictions (many Ukrainians were already allowed to work in Poland and Hungary) when in 2014 they were offered a partnership With. It was very far from being anything close to opening up any negotiations for the Ukraine to join the European Union but Ukrainians started dreaming. The dream was shattered when the Ukrainian government was told by the European Union that it had to choose between their offer and another deal of partnership with China, Russia and Eurasian countries and the Ukrainian president chose the Asian solution. That started the maidan revolution.

To be continued

NOTES

[1] This was also the case in Georgia where the Orthodox Church held services in the local language centuries before Slavs had ever heard of Christianity.