Texts, photographs, links and any other content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.

Do not miss these feature stories in this Issue 5 (Winter-Spring 2021) of N&C Nature & Cultures:

"Thalassa's" Georges Pernoud (1947 - 2021)” a tribute to one of France's icons of travel journalism; “Borders and identities - Let us change our way of thinking” by Dr. by Katja Banik; "An emblematic geopolitical journal in Germany: the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (1924-1944) and its newsworthiness"

by Prof. Goran Sekulovski; "The Chernobyl effect: did ecological damage bring down the Soviet-model régimes of Central and Eastern Europe?" by Colin Hardage; "The Chinese Communist Party and the Environment" by Caleb Lemke. Plus our permanent features: The Nature & Cultures electronic library, and our mini-encyclopedia of constitutional systems country by country: The Comparative Government Project

"Thalassa's" Georges Pernoud (1947 - 2021)” a tribute to one of France's icons of travel journalism; “Borders and identities - Let us change our way of thinking” by Dr. by Katja Banik; "An emblematic geopolitical journal in Germany: the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (1924-1944) and its newsworthiness"

by Prof. Goran Sekulovski; "The Chernobyl effect: did ecological damage bring down the Soviet-model régimes of Central and Eastern Europe?" by Colin Hardage; "The Chinese Communist Party and the Environment" by Caleb Lemke. Plus our permanent features: The Nature & Cultures electronic library, and our mini-encyclopedia of constitutional systems country by country: The Comparative Government Project

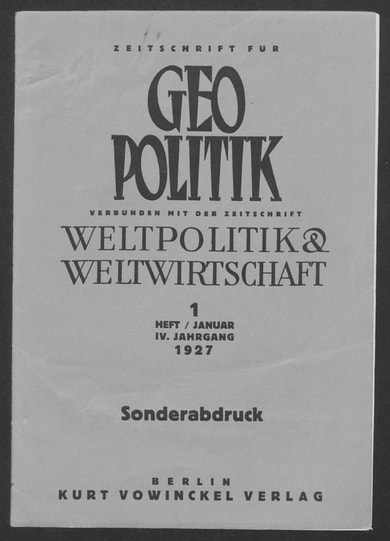

reference in geopolitical thought before and during the Second World War and a source of incessant debate ever since, the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (Magazine or Notebooks for Geopolitics) receives exceptional treatment in specialized libraries. Its crucial concepts such as Lebensraum (Vital space), Deutschtum (“Germanity”), its original iconography, its analysis of geopolitics from multiple perspectives, and its undeniable influence on its contemporaries make it a highly priced collection in any library catalog.

|

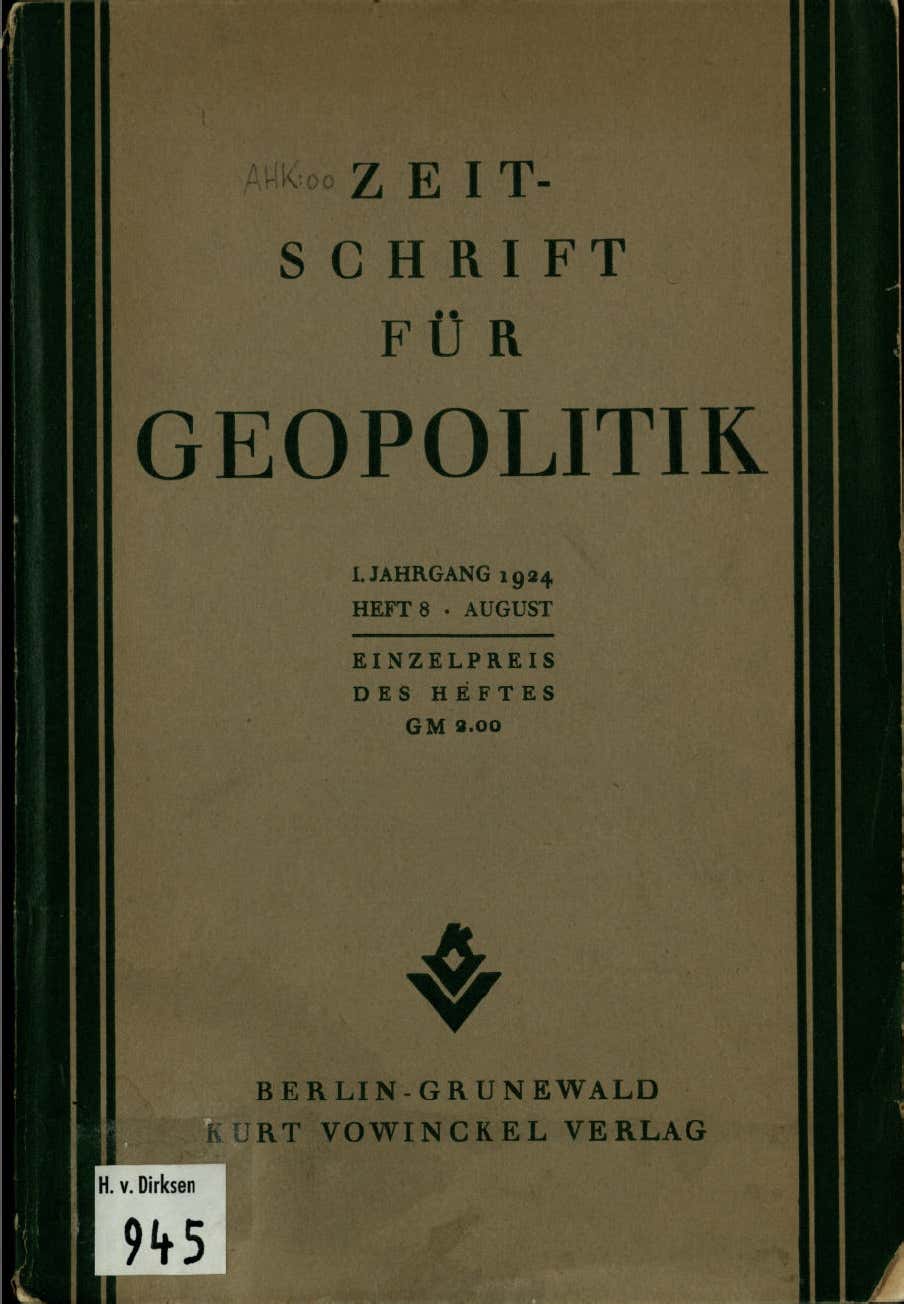

Two examples explain this return to favor of geopolitics: the foundation by the politician Marie-France Garaud in 1982 of the journal Géopolitique intended for the general public, as well as the addition in 1983 of a subtitle to the journal Hérodote founded in 1976 by Yves Lacoste which henceforth became a “review of geography and geopolitics ”. Launched in Heidelberg (Baden-Württemberg Land) five years after the Treaty of Versailles (1919), the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik established itself as the great German journal of

geopolitics of the interwar period. The publication, which began in 1924, ends in 1944 before resuming life in a new form in 1951 until 1968. This entire corpus deserves special attention from researchers and students in geography, as well as in social and political sciences in general. We will try here to give them a taste of why their interest will be rewarded. To do this, this presentation of the journal will revolve around three axes: an opening centered on the very word “geopolitics”, a central section addressing the crucial phases of the Zeitschrift (between 1924 and 1944) which will also include the cartographic aspect of the review and an annexed part relating to the reception of the journal, notably through the relations of German Geopolitik and French geopolitics, and a conclusion which will revisit the value of this collection for contemporary research in geopolitics and try to show why Geopolitik can still attract geographers and researchers in the humanities and social sciences. It was with the 1980s that Geopolitics / Geopolitik were revived by politicians and academic researchers, the word having been almost completely banned from the lexicon because of its ideological connotation after the Second World War. |

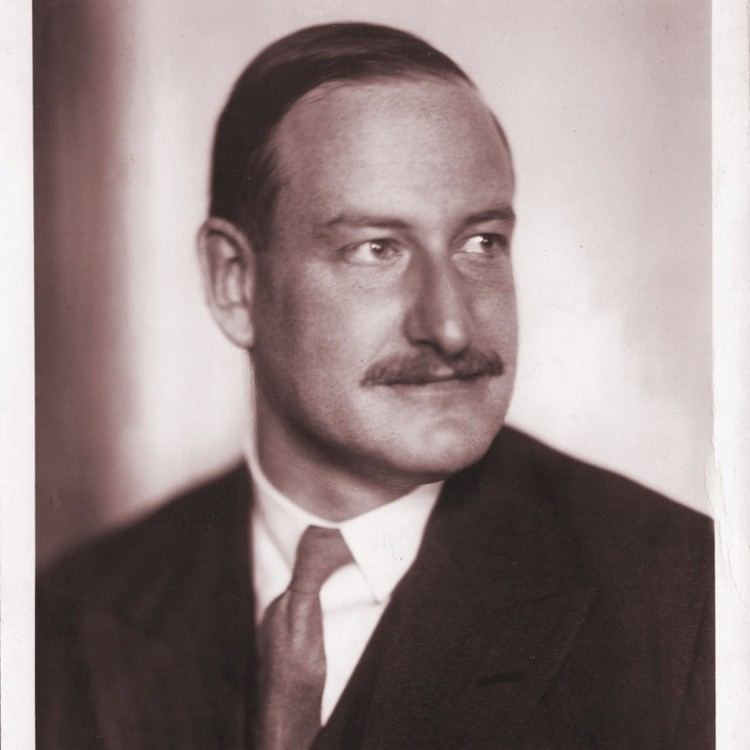

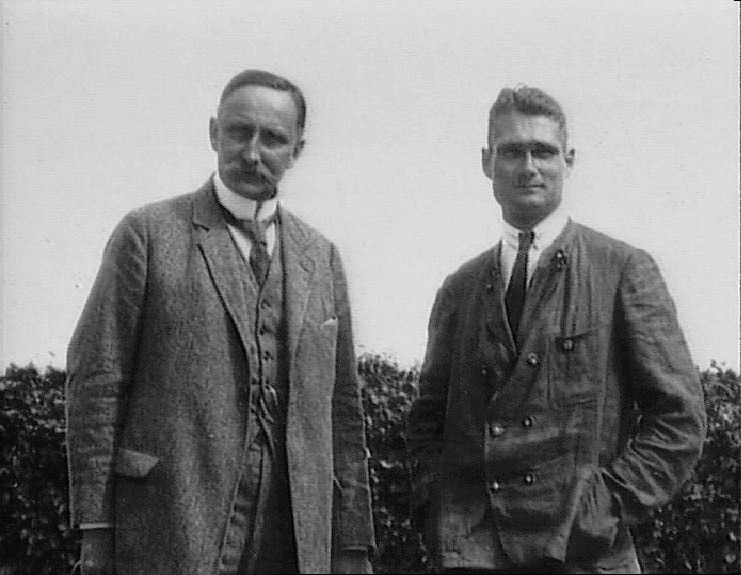

The fall of the Berlin wall also saw the emergence of an important reflection on geopolitics in general, on the relationship between political geography and geopolitics in higher education but also on certain points made about the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , in particular by the French Germanist Michel Korinman (Korinman, 1990), and the Swiss geographer Claude Raffestin (Raffestin, 1995) which alone represent a solid basis for our analysis. Finally, the evaluation of the relationship between the founder of the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , Karl Haushofer, on the one hand, and the National Socialist régime, on the other hand, also gave birth to analyzes on the possible continuity between the themes developed by the concepts, maps or speeches of the promoter of German Geopolitik and its political accomplishments, making Haushofer both a disciple of Ratzel's and a master of Hitler, through Rudolf Hess (Herwig, 2016; Murphy, 2014; Herb, 1997; Heske, 1986). More nuanced studies on the complex relations between geographers and geopoliticians of the time and political decision-makers (Barnes and Abrahamsson, 2015; Ebeling, 1994; Natter, 2004) must not be forgotten either.

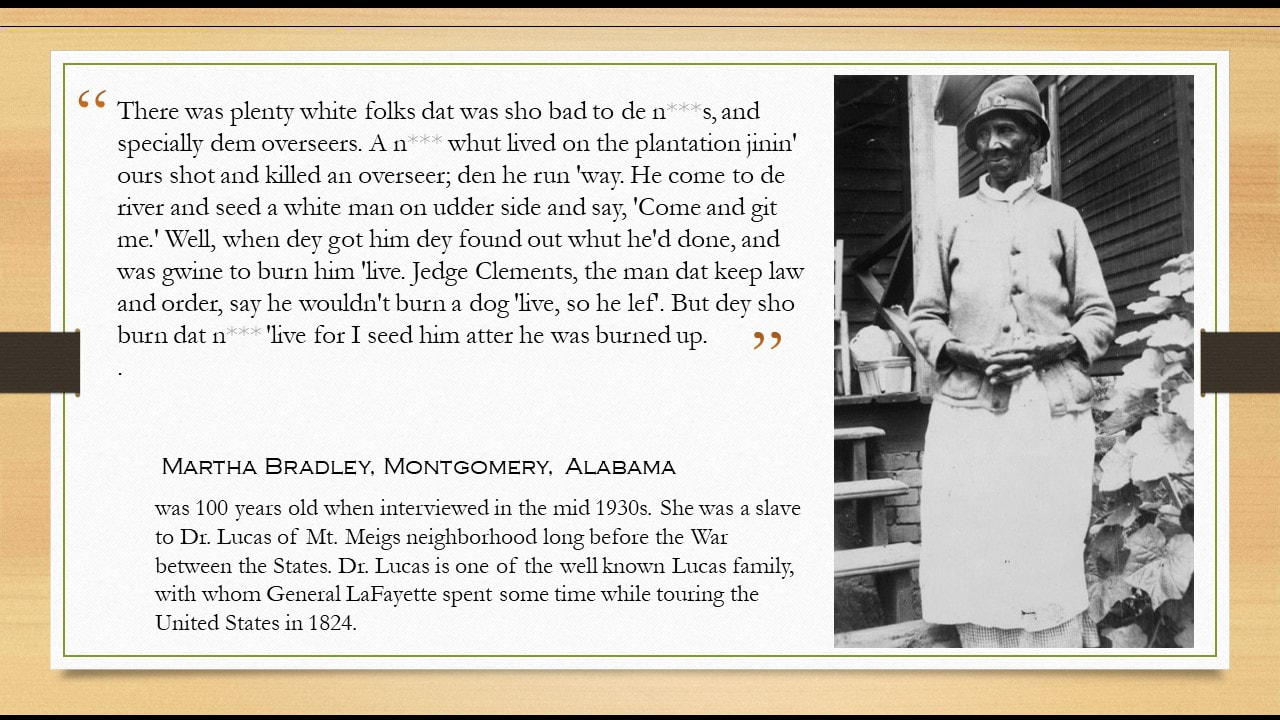

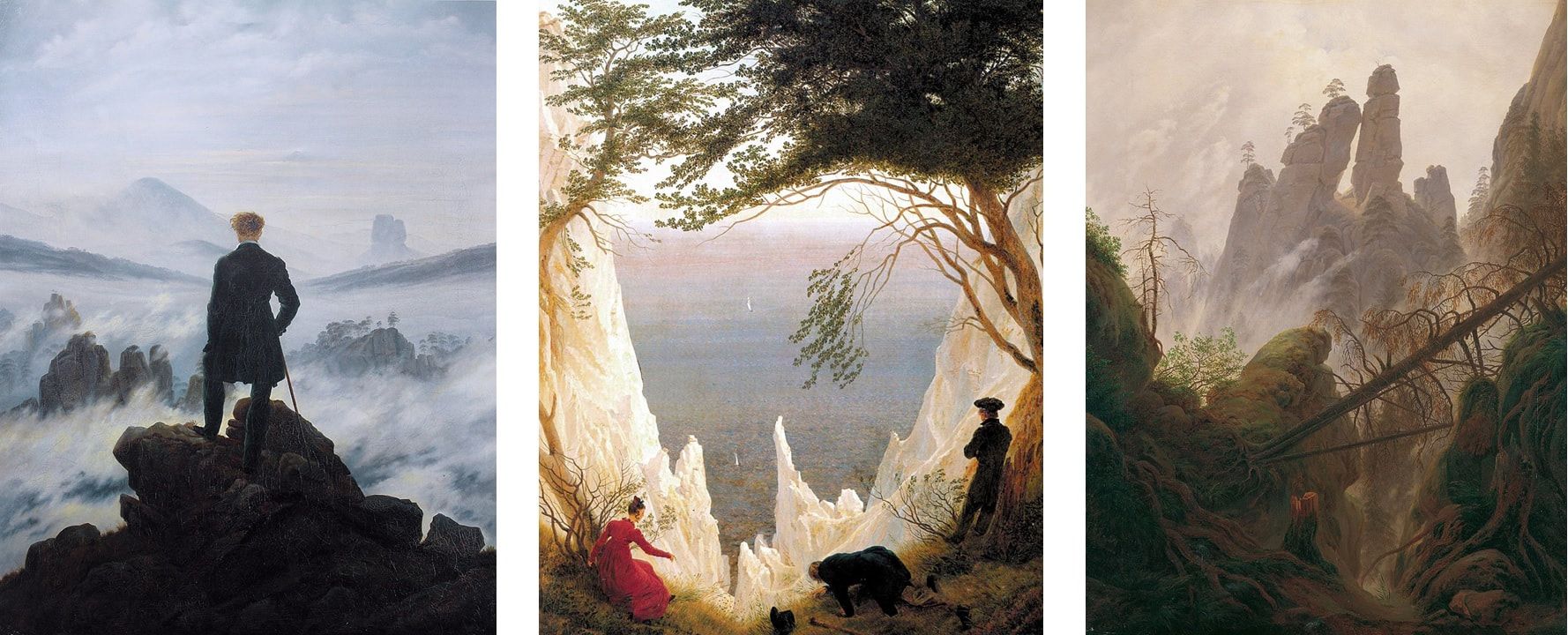

Does a sense of awe in front of such German landscapes, define German identity? Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), one of the most influential German painters of romanticism, as well as other artists (such as the Düsselorf School painters) and writers of the same movement such as Schelling, Novalis or Tieck, impressed upon German culture a reverence when contemplating nature. This sense of space is also what characterizes the German geographic school which emerged at the same time. In his essay "Paysages Politiques" ("Political Landscapes") French analyst of geopolitics and leading post-modern geographer Yves Lacoste deconstructed the works of Friedrich and others as icons that served to forge a representation of a common identity for Germans divided until then by multiple political borders, religious divisions and linguistic differences. The rise of Nazism in the early 1930s saw a resurgence in Friedrich's popularity, followed by a sharp decline as his paintings were, by association with the Nazi movement, interpreted as having a nationalistic aspect. The same happened to the discipline of geopolitics seen as a tool of Nazi propaganda, in great part due to the role played by Karl Haushofer’s geographic journal.

|

Geopolitics: what does this name designate? The burden of the term geopolitics as well as its resonance are unequivocal today. Thecontemporary titanic work undertaken by contemporary geopoliticians to define geopolitics reminds us that words are not innocent. Although most geopolitical textbooks agree on the origin of the word, launched by the Swedish scholar Johan Rudolf Kjellén (1864-1922) to the beginning of the 20th century, geopolitics has a much older date of birth. Insistingly investigating Kjellén or Friedrich Ratzel (see below ) to find a paternity for the term, we forget that the one who used it for the first time, is most likely the German philosopher and librarian Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) in his project for an Encyclopedia of 1679 where he foresaw a new classification of sciences, devoting a section to what he first called “Cosmopolitics”, a term replaced in favor of “geopolitics” (Louis, 2014). |

|

|

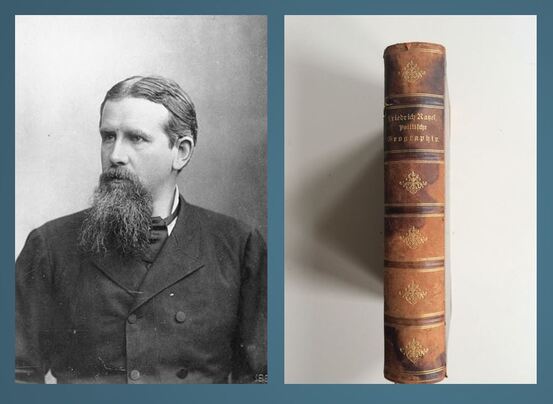

Forgotten afterwards for the next two centuries, “geopolitics” reappears at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries bearing the marks of a separate academic discipline, thanks to Friedrich Ratzel, professor of geography at the University of Leipzig, often considered,as the "founding father" of the discipline … although he didn't use the word. Influenced by Darwin (1809-1882) and evolutionist theories of his time, in his now classic work Political Geography (1897), Ratzel emphasized the geographical dimension of the State at the center of spatial politics, as well as on the power of natural environments over human societies. Karl Haushofer, a promoter of German Geopolitik? In a straight line of succession of Ratzelian thought, and in the complex geopolitical context of Germany’s defeat in 1918 and the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, comes Karl Haushofer (1869-1946), former soldier and professor of geography at the University of Munich. In the person of Karl Haushofer geopolitics has a proper name, a concrete face. However, one should not fall into the trap of making Haushofer a precursor of German geopolitics because the historian of science and epistemologist George Canguilhem (1968) taught us to beware of this term, so that it is not used lightly. |

|

The review itself

Haushofer did not act alone. Surrounded by geographers and political scientists Erich Obst, Hermann Lautensach, Fritz Hesse, Otto Maull, under the auspices of the publisher Kurt Vowinckel, Haushofer lead a small editorial committee overseeing the new periodical, the objective of which was threefold: to treat the news in editorials; to discuss specific contemporary issues in articles; and publish detailed summaries of geopolitical phenomena in the Old World, in the Atlantic realm and in Asia in the form of reports. Coverage of geographical areas was distributed along these lines: Haushofer, a specialist of Japan, was responsible for following the events of the Indo-Pacific area (the assignment of this section, unlike the others, remained unchanged until the demise of the review); Obst took care of Europe, to which and to which was associated North Africa; Maull dealt with America and the rest of Africa, and Lautensach was responsible for a “global” and “systemic” section. In the Thirties, it was Albrecht Haushofer, son of Karl, who took over from Maull (Kleinschmager, 1988). These were the major areas of geopolitical covered on a regular basis and with sustained frequency ranging from one to six times a year depending on the featured subjects. |

Frequency and number of articles

Since the first issue of January 1924, the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik was a monthly publication. Between 1924 and 1944 the Zeitschrift published a total of 1269 essays and position papers, written by 619 authors (Natter, 2003). During its ten first years, the journal attracted contributions from the majority of scholars writing on political geography established in Germany, while remaining open to geographers from many other countries (including the USSR) whose leaders were more or less explicitly in favor of the “revision” of the Treaty of Versailles (Lacoste, 2012).

Since the first issue of January 1924, the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik was a monthly publication. Between 1924 and 1944 the Zeitschrift published a total of 1269 essays and position papers, written by 619 authors (Natter, 2003). During its ten first years, the journal attracted contributions from the majority of scholars writing on political geography established in Germany, while remaining open to geographers from many other countries (including the USSR) whose leaders were more or less explicitly in favor of the “revision” of the Treaty of Versailles (Lacoste, 2012).

|

As for the circulation and the subscribers, the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik printed at 800 copies in 1924, had 1,500 subscribers by the end of 1925, reached 2,000 subscribers in November 1926 and became the best-selling geography journal sold internationally (compared in particular to to its illustrious rival, the Geographische Zeitschrift ).

Each issue, of approximately a hundred pages, generally contained one or more leading articles, ("Aufsätze" – presentations / essays), then geopolitical reports (“Geopolitische Berichterstattungen”), geopolitical surveys (“Geopolitische Untersuchungen”) or the treatment of substantive issues (“Grundfragen”), and finally book reviews (“Literaturbericht” or “Schrifttum”). The latter, after 1935, became very brief reports (Büchertafel) reduced to two or three lines. In the same year, appeared a digest section (Späne), proposed by the Arbeitgemeinschaft für Geopolitik (Working group on geopolitics, close to the National Socialist Party of German Workers, the NSDAP) consisting of very short notes on questions of geopolitical interest, collected in other geopolitical journals. Founded in 1895 by Alfred Hettner, professor at the University of Heidelberg, who followed her closely until his death in 1941, the Geographische Zeitschrift is a German journal of geography which wants to be theoretical. Nature and purpose of the review

In view of its content, it emerges that the journal's inclusion in the academic field of geography, in this case political geography, does not make it a classic academic journal. Halfway between an academic journal and a magazine, the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik was rather intended for an audience of geographers with an interest in political and economic questions, more particularly in their international dimension, not necessarily for members of the academic community. It was also aimed at non-specialists, journalists, politicians and particularly affected teachers (who formed a third of subscribers |

in 1927, according to publisher Vowinckel). Although the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik never became a magazine, it has deliberately removed complex professional jargon from its issues (Harbeck, 1963). The objective was to be an information instrument, but also, one of initiation and training in geopolitics. Given the particular definition of the latter, the journal was also intended as an instrument of political influence, indirectly in the beginning, much more explicitly since the end of the nineteen-twenties, and in favor of National Socialism. However, it cannot be interpreted as an organ of the National Socialist Party of German Workers (the NSDAP, often referred to as the Nazi party or the National Socialist Party), to which Karl Haushofer himself apparently never belonged (Ebeling, 1994), although he had very close ties with some of his members, and especially with Rudolf Hess, Hitler's right-hand man (Herwig, 2016).

The aim of the review according to Haushofer was rather to highlight the importance of geopolitical policy and, specifically for Germany, to draw attention to the fact that it must extend its hold over Mitteleuropa to ensure control of a living space (Lebensraum) (Heske, 1986) necessary for the well-being of its people (Natter, 2004).

The aim of the review according to Haushofer was rather to highlight the importance of geopolitical policy and, specifically for Germany, to draw attention to the fact that it must extend its hold over Mitteleuropa to ensure control of a living space (Lebensraum) (Heske, 1986) necessary for the well-being of its people (Natter, 2004).

The main phases of the journal's life

While Karl Haushofer's continued editorial involvement may suggest that the journal served as a body that continually reflected his views between 1924 and 1944, the situation is much more complex. The history of the journal reveals many developments revealing three clearly distinct phases characterized by the content, by the list of contributors as well as by the editorial board: 1924-1931, 1931-1940 and 1940-1944.

— During the first phase of the newspaper, completed in 1931 when Haushofer had become editor-in-chief, each of the main co-editors was responsible for publishing about well-defined geographic areas. The objectives were to provide knowledge for political decision-making and consolidate geopolitics as a recognized academic discipline, as a sub-field of political geography.

While Karl Haushofer's continued editorial involvement may suggest that the journal served as a body that continually reflected his views between 1924 and 1944, the situation is much more complex. The history of the journal reveals many developments revealing three clearly distinct phases characterized by the content, by the list of contributors as well as by the editorial board: 1924-1931, 1931-1940 and 1940-1944.

— During the first phase of the newspaper, completed in 1931 when Haushofer had become editor-in-chief, each of the main co-editors was responsible for publishing about well-defined geographic areas. The objectives were to provide knowledge for political decision-making and consolidate geopolitics as a recognized academic discipline, as a sub-field of political geography.

|

— It was during the second period (1931-1940) that the review also encountered economic difficulties: its volume fell from 1126 pages in 1929 to 912 in 1931. The crises of that period were somewhat resolved by the departure in 1931 of the other members of the editorial staff and the transfer of exclusive editorial control to Haushofer although with the continued participation of Vowinckel, the publisher, and the appointment of Albrecht Haushofer, Karl's son, as editor-in-chief.

The creation within the journal of an Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Geopolitik (Study group in geopolitics) in 1932, then its development and funding by the National-Socialist Party helped to increase the circulation of the Zeitschrift, which rose from 3000 to 4000 copies around 1930 to 7,500 in 1933 (Ó Tuathail, 1996) [i]. Throughout this second phase the Zeitschrift was to serve as an instrument for the education of German leaders and also as an educational tool to durably instill geopolitical thinking habits into the minds of the general public. According to Natter (2003), what seemed most lacking in the training of German youths after the war was the ability to think in terms of large spaces, continents. Geopolitics sought to broaden the geographical vision of the German nation. It was about teaching the German people to think in terms of global spaces, or Grossraum ("large space"). This second phase ended with the declaration of war against the Soviet Union and Albrecht Haushofer resignation from his editorial position. |

— During the third phase of its existence (1940-1944), the review accumulated difficulties. As early as June 1939, the publisher of the review Vowinckel expressed his worries to the Ministry of Propaganda about its support for the magazine in the event of war; this could not prevent the monthly issues, affected by the restrictions on paper, from diminishing by 40 pages in October of the same year. Many readers then cancelled their subscription.

The volume of the journal continued to decrease from year to year: 562 pages in 1942, 347 in 1943. Consequently, the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik began delivering double issues. Gradually, contributions by Haushofer, who remained the editor of the periodical, were reduced, as in August 1943, to a sort of catalog of keywords, to a sequence of dates. The end was near. The union of magazine publishers, on September 2, 1944, gave the order to cease publication, and this became final on the 1st of October, after a life-span of twenty-one years.

— During the third phase of its existence (1940-1944), the review accumulated difficulties. As early as June 1939, the publisher of the review Vowinckel expressed his worries to the Ministry of Propaganda about its support for the magazine in the event of war; this could not prevent the monthly issues, affected by the restrictions on paper, from diminishing by 40 pages in October of the same year. Many readers then cancelled their subscription.

The volume of the journal continued to decrease from year to year: 562 pages in 1942, 347 in 1943. Consequently, the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik began delivering double issues. Gradually, contributions by Haushofer, who remained the editor of the periodical, were reduced, as in August 1943, to a sort of catalog of keywords, to a sequence of dates. The end was near. The union of magazine publishers, on September 2, 1944, gave the order to cease publication, and this became final on the 1st of October, after a life-span of twenty-one years.

|

Karl Haushofer committed suicide in 1946, although, after investigation, he was exonerated of having been a supporter of the Nazi party. Not only did the word geopolitics become taboo after 1945, but the “denazification” measures taken by the Allies minimized the portion of geography and history in the curricula of secondary schools and universities, based on the argument that it had favored Nazism.

Since 1951, a revised version of the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik, bearing the same name by the same publisher with the mention "22. Jg." (22nd year), tried to give another image to geopolitics by giving it a more geo-sociological orientation and by emphasizing the peaceful development of the world. Mostly professors, journalists and businessmen were among the collaborators of the renovated journal, not to mention the name of Countess Marion Dönhoff, future director of the great German weekly Die Zeit. However, the real influence or interest in the new publication published between 1951 and 1968 remained very limited; in its new form, as an intellectual medium, the periodical was finished. |

onography, the map, and the politics of image

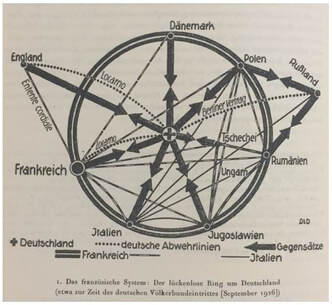

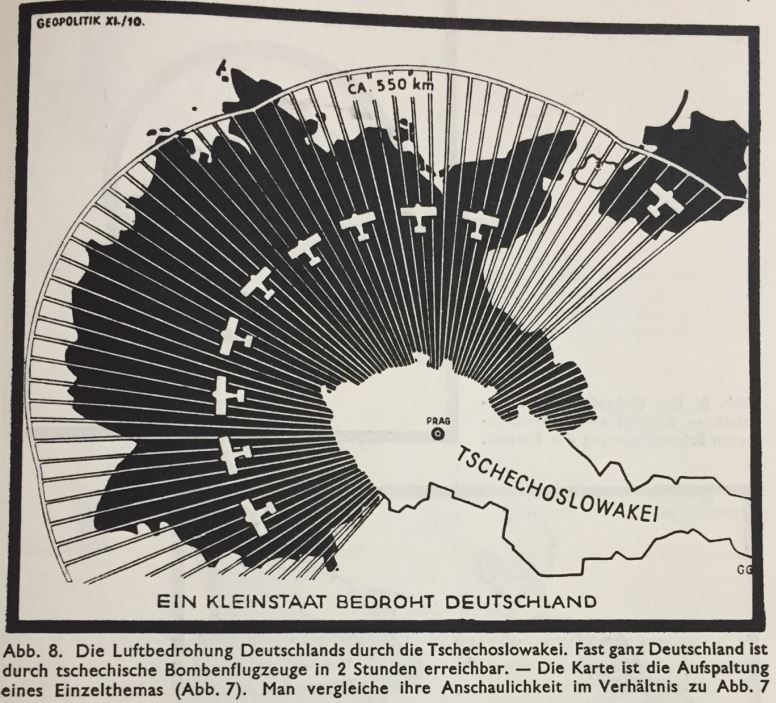

One of the objectives of the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik was also to give a "real" image of the world, which explains why the journal was at the origin of a vast "iconographic" entreprise, intended for persuasion. In cartography, geopolitics found an ideal medium: having become propaganda aimed at the reader and his visual perception, cartography translates with great efficiency an important "message", in order to encourage a reaction.

In a classic article on cartography from 1934 (N ° 10, p. 635-652), journalist Rupert von Schumacher offers a “Zur Theorie der Raumdarstellung” (Theory of spatial representation) in which he provides keys to understanding this theory, not to mention the many illustrations provided by the journal between 1924 and 1944. Three years later (1937), the same author published a “Theorie der geopolitischen Signatur” (Theory of the geopolitical signature) which again underlines the importance of geopolitical mapping. Space and territory are seen through the prism of the object to be obtained, grasped or encircled (Raffestin 1995). We observe a kind

of representation of a future world which is fluctuating and in which everything is in formation and in which, at the same time, everything is potentially a prey soon to be seized. These maps create graphic images of potential conflicts some of which, will erupt during World War II of which they will even be the trigger.

One of the objectives of the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik was also to give a "real" image of the world, which explains why the journal was at the origin of a vast "iconographic" entreprise, intended for persuasion. In cartography, geopolitics found an ideal medium: having become propaganda aimed at the reader and his visual perception, cartography translates with great efficiency an important "message", in order to encourage a reaction.

In a classic article on cartography from 1934 (N ° 10, p. 635-652), journalist Rupert von Schumacher offers a “Zur Theorie der Raumdarstellung” (Theory of spatial representation) in which he provides keys to understanding this theory, not to mention the many illustrations provided by the journal between 1924 and 1944. Three years later (1937), the same author published a “Theorie der geopolitischen Signatur” (Theory of the geopolitical signature) which again underlines the importance of geopolitical mapping. Space and territory are seen through the prism of the object to be obtained, grasped or encircled (Raffestin 1995). We observe a kind

of representation of a future world which is fluctuating and in which everything is in formation and in which, at the same time, everything is potentially a prey soon to be seized. These maps create graphic images of potential conflicts some of which, will erupt during World War II of which they will even be the trigger.

|

Images are also often used to construct the enemy from scratch. The assumption of geopolitics is that anyone can be an enemy and, therefore, can

be attacked. From this point of view, geopolitics is more like a “wargame” than a scientific discipline seeking to identify spatial entities (Raffestin, 1995). The expression of this friend-foe relationship finds its style in geometric representations as seen for example in the diagram of 1927 entitled "The French system: encirclement around Germany (at the time of the entry of Germany in the League of Nations in 1926)” (fig. 2). This is an "encirclement" or a "belt" around German territory. The friend-enemy dialectic is present in its elementary form: Germany is locked up in a belt, which only an alliance with Russia could break since the latter is the enemy of Poland and Romania, themselves enemies of Germany. |

Most of the articles which deal with the geopolitical situation of Germany, in its immediate—or much more distant—entourage, are illustrated by black and white maps, dramatic and simplifying, with arrows pointing to the flow of spatial areas (Herb, 1996). In this perspective, the representation of the Czechoslovak threat on

Germany, published in the article by von Schumacher (1934) is very significant . The exact title of this map is: “The Air Threat on Germany Across Czechoslovakia. Almost all of Germany can be reached by Czech bombers in 2 hours”. The map denounces the expansionist aims of the Czechs on all

parts of the German Reich.

A final example of the development of this new cartographic language is the illustration of the perceived favorable position of French geopolitics and of Central and Eastern Europe compared to that of Germany and Italy. The map appeared in Karl Haushofer's article from 1932 entitled “Rückblick und Vorschau auf das geopolitische Kartenwesen” (Review and overview of geopolitical cartography); once again, circles and arrows were used in this map to make an impression on the recipients of the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , and highlight the security challenges of Germany and Italy.

Germany, published in the article by von Schumacher (1934) is very significant . The exact title of this map is: “The Air Threat on Germany Across Czechoslovakia. Almost all of Germany can be reached by Czech bombers in 2 hours”. The map denounces the expansionist aims of the Czechs on all

parts of the German Reich.

A final example of the development of this new cartographic language is the illustration of the perceived favorable position of French geopolitics and of Central and Eastern Europe compared to that of Germany and Italy. The map appeared in Karl Haushofer's article from 1932 entitled “Rückblick und Vorschau auf das geopolitische Kartenwesen” (Review and overview of geopolitical cartography); once again, circles and arrows were used in this map to make an impression on the recipients of the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , and highlight the security challenges of Germany and Italy.

The foundations of this very particular cartography are explained by Karl Haushofer in the same article on geopolitical cartography but also by Walter Jantzen in an article published in 1942 on “geopolitics in cartographic imaging” (“Geopolitik im Kartenbild) ”. The undeniable force of the visual impact of Zeitschrift mapping, is largely due to the simplification, even the schematization of geographic representations, to the amplification of certain features or to free figurations in hasty sketches. It is a set of processes that really compose the map as a dramatization or, according von Schumacher's expression, as a " poster ", and not as a representation of reality, even less as a research tool. The map is therefore no longer a representation of a real situation, but rather the representation of a project including the dream of territorial expansion. These are propaganda maps that take on very sophisticated shapes. Indeed, the image in the Zeitschrift potentiates the present and updates the future. The almost permanent lack of scale on these maps is a very revealing element. All this confirms the significance of the journal and still calls for in-depth studies on this cartography developed within the framework of the Zetischrift .

Reception of the journal: French geopolitics versus German Geopolitik

French geographers, from their opposing position, help to understand the notion of geopolitik developed in the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik. For example, during the period between the wars, Albert Demangeon (1872-1940), a good connoisseur of German publications, wondered “how did the young (German) school of geopolitics depart from Ratzel? It has marked itself apart from [Ratzel] by its tendencies to stray too far from the scientific spirit, must we say with regret. It defines the state as not only as a living organism, but also as conscious entity endowed with will ” (Demangeon, 1932). But the French geographer does not stop there. Writing about the foundation of this new discipline, he notes that: “geopolitics is a machination, a war machine; if it wants to count among the sciences, it is time that it returned to political geography ” (Ibid, p. 26).

According to a note by Michel Korinman (1990), Albert Demangeon would have possessed years of volumes of Zeitschrift für Geopolitik annotated by his hand which was later transmitted to Library of the Institute of Geography of Paris [ii].

The October 1932 issue of the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (fig. 5) includes an entire series of excerpts of French texts criticizing Geopolitik (“Französischer Kampf gegen die Geopolitik”). It is interesting that Karl Haushofer preceded this series with his contribution “Geopolitik in Abwehr und auf Wacht (“Geopolitics in Defense and on the Lookout”), where he replies in particular to Albert Demangeon:“ the French want the Germans to correct themselves by becoming 'scientists' again because they have been practicing geopolitics for a long time – for example in Central Europe where they [the French] are linked with the Danubian confederation project dear to André Tardieu. Their crusade against the 'dangerous geopolitics' is not neutral ”. (Haushofer, 1932).

For his part, the French geographer Jacques Ancel (1879-1943), specialist in the political geography of the Balkans, author of a thesis on Macedonia, somewhat refined the criticism and had a rather positive outlook on the magazine. According to him, “Geopolitik is a German science” and he notes, concerning Haushofer’s circle: “this new school grouped around the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik which is already eight years old [in 1932], which is full of happy innovations, crisp and clear cartographic schematics, models, political chronicles that are on the lookout for the avatars of the world, achieves a balance between economy and politics, all enveloped with a certain luminous ease that used to pass for being exclusively Latin and mainly educational”. (Ancel, 1932). In his work entitled Geopolitics (1936), Jacques Ancel continues his criticism and takes a more accentuated stand against “the Geopolitik of those German professors to whom Pan-German Hitlerism borrowed its reason and its 'vocabulary' ”. In 1938, he also wrote a Geography of Borders , where he revisits the question of the influence of haushoferian theses on the geographical conceptions of the Third Reich regarding German expansionism ( Lebensraum ). Moreover, Karl Haushofer was to review this last book by Ancel in the 1940 Zeitschrift für Geopolitik n ° 3 (p. 149), with the title “Strebepfeiler zur Geopolitik (Pillar of geopolitics)”.

Finally, the very evocative term of geopolitics thus found a favorable ground in France after 1936, thanks to Jacques Ancel’s publication. It was also during this period, in 1938, that was published the only article in French in the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik by Georges Delamare (1938), dealing with the problem of television in the context of a whole series of articles devoted to the relationship of geopolitics with radio and television.

Conclusion

The Zeitschrift für Geopolitik is undoubtedly an exceptional geography review, specializing in geopolitics, which deserves the attention of researchers in many ways. It represents an attempt to set itself apart from other journals of the same period by a style that escapes the “classic” university spirit, a captivating presentation, original iconography and a concern to approach space on a global scale in order to give a global vision of international issues. Totaling an abundant volume of almost 40,000 pages of text, the Zeitschrift has never stopped developing specific theses and concepts, a detailed reading of which will identify the close link between geography and German policy of the interwar period and the crucial years of WWII.

This still raises the question of the epistemological status of political geography today as well as of political science. It still raises the problem of the relation of science to its object, in other words of geopolitics to applied politics and to political ideologies.

The compromise of the editor, Karl Haushofer, with National Socialism German was complicated, indirect. His life and that of his son are very instructive, not so much because they were actors responsible for major facts (or not) (Murphy 2014) but because these lives illustrate the complex relationship between Nazism and its use of academic work, in this case the academic work of geographers. National Socialism was obsessed with space and spatial categories as well as with spatial transformation. It's hard to claim that this obsession is directly inspired by Haushofer, but part of his geographical imagination and his vocabulary presumably struck the leaders of the Nazi Party. Like other geographers of the time, whose ideas were used by the Nazis, Haushofer’s complicity with the program of the National Socialist Party was probably entangled in a moral by a struggle (Barnes and Abrahamsson, 2015).

From there, it is difficult to draw a line between scientific research and ideologically engaged works of the period, or to distinguish objective works from those that have suffered political distortion. The history of geographic thought should not only critically question the connivance of geographers and their geographical imagination with the tragedies of the past and present, but also explore these complicities, at the same time wondering about the possible moral struggles

of the actors involved. The case of the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik and the geographer Haushofer illustrate the difficulty in drawing the lines between the actors.

This is why this important collection of the Zeitshchrift für Geopolitik, represents indispensable reading, allowing researchers a fundamental investigation into the complex relationship between science and ideology. Finally, although it has collapsed as a science by ceding its place to political science, geopolitics in Germany, will always give the impression of being one of these dormant volcanoes which make it difficult to be reassured that they will never reactivate. Hence the need to know this flagship geopolitical review covering one of the most memorable periods in history.

French geographers, from their opposing position, help to understand the notion of geopolitik developed in the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik. For example, during the period between the wars, Albert Demangeon (1872-1940), a good connoisseur of German publications, wondered “how did the young (German) school of geopolitics depart from Ratzel? It has marked itself apart from [Ratzel] by its tendencies to stray too far from the scientific spirit, must we say with regret. It defines the state as not only as a living organism, but also as conscious entity endowed with will ” (Demangeon, 1932). But the French geographer does not stop there. Writing about the foundation of this new discipline, he notes that: “geopolitics is a machination, a war machine; if it wants to count among the sciences, it is time that it returned to political geography ” (Ibid, p. 26).

According to a note by Michel Korinman (1990), Albert Demangeon would have possessed years of volumes of Zeitschrift für Geopolitik annotated by his hand which was later transmitted to Library of the Institute of Geography of Paris [ii].

The October 1932 issue of the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (fig. 5) includes an entire series of excerpts of French texts criticizing Geopolitik (“Französischer Kampf gegen die Geopolitik”). It is interesting that Karl Haushofer preceded this series with his contribution “Geopolitik in Abwehr und auf Wacht (“Geopolitics in Defense and on the Lookout”), where he replies in particular to Albert Demangeon:“ the French want the Germans to correct themselves by becoming 'scientists' again because they have been practicing geopolitics for a long time – for example in Central Europe where they [the French] are linked with the Danubian confederation project dear to André Tardieu. Their crusade against the 'dangerous geopolitics' is not neutral ”. (Haushofer, 1932).

For his part, the French geographer Jacques Ancel (1879-1943), specialist in the political geography of the Balkans, author of a thesis on Macedonia, somewhat refined the criticism and had a rather positive outlook on the magazine. According to him, “Geopolitik is a German science” and he notes, concerning Haushofer’s circle: “this new school grouped around the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik which is already eight years old [in 1932], which is full of happy innovations, crisp and clear cartographic schematics, models, political chronicles that are on the lookout for the avatars of the world, achieves a balance between economy and politics, all enveloped with a certain luminous ease that used to pass for being exclusively Latin and mainly educational”. (Ancel, 1932). In his work entitled Geopolitics (1936), Jacques Ancel continues his criticism and takes a more accentuated stand against “the Geopolitik of those German professors to whom Pan-German Hitlerism borrowed its reason and its 'vocabulary' ”. In 1938, he also wrote a Geography of Borders , where he revisits the question of the influence of haushoferian theses on the geographical conceptions of the Third Reich regarding German expansionism ( Lebensraum ). Moreover, Karl Haushofer was to review this last book by Ancel in the 1940 Zeitschrift für Geopolitik n ° 3 (p. 149), with the title “Strebepfeiler zur Geopolitik (Pillar of geopolitics)”.

Finally, the very evocative term of geopolitics thus found a favorable ground in France after 1936, thanks to Jacques Ancel’s publication. It was also during this period, in 1938, that was published the only article in French in the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik by Georges Delamare (1938), dealing with the problem of television in the context of a whole series of articles devoted to the relationship of geopolitics with radio and television.

Conclusion

The Zeitschrift für Geopolitik is undoubtedly an exceptional geography review, specializing in geopolitics, which deserves the attention of researchers in many ways. It represents an attempt to set itself apart from other journals of the same period by a style that escapes the “classic” university spirit, a captivating presentation, original iconography and a concern to approach space on a global scale in order to give a global vision of international issues. Totaling an abundant volume of almost 40,000 pages of text, the Zeitschrift has never stopped developing specific theses and concepts, a detailed reading of which will identify the close link between geography and German policy of the interwar period and the crucial years of WWII.

This still raises the question of the epistemological status of political geography today as well as of political science. It still raises the problem of the relation of science to its object, in other words of geopolitics to applied politics and to political ideologies.

The compromise of the editor, Karl Haushofer, with National Socialism German was complicated, indirect. His life and that of his son are very instructive, not so much because they were actors responsible for major facts (or not) (Murphy 2014) but because these lives illustrate the complex relationship between Nazism and its use of academic work, in this case the academic work of geographers. National Socialism was obsessed with space and spatial categories as well as with spatial transformation. It's hard to claim that this obsession is directly inspired by Haushofer, but part of his geographical imagination and his vocabulary presumably struck the leaders of the Nazi Party. Like other geographers of the time, whose ideas were used by the Nazis, Haushofer’s complicity with the program of the National Socialist Party was probably entangled in a moral by a struggle (Barnes and Abrahamsson, 2015).

From there, it is difficult to draw a line between scientific research and ideologically engaged works of the period, or to distinguish objective works from those that have suffered political distortion. The history of geographic thought should not only critically question the connivance of geographers and their geographical imagination with the tragedies of the past and present, but also explore these complicities, at the same time wondering about the possible moral struggles

of the actors involved. The case of the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik and the geographer Haushofer illustrate the difficulty in drawing the lines between the actors.

This is why this important collection of the Zeitshchrift für Geopolitik, represents indispensable reading, allowing researchers a fundamental investigation into the complex relationship between science and ideology. Finally, although it has collapsed as a science by ceding its place to political science, geopolitics in Germany, will always give the impression of being one of these dormant volcanoes which make it difficult to be reassured that they will never reactivate. Hence the need to know this flagship geopolitical review covering one of the most memorable periods in history.

Afterword: the tragic end of Haushofer, of his wife and of his son.

After the the Nazis seized power in 1933, Haushofer remained friendly with Hess, who protected Haushofer and his wife from the racial laws of the Nazis,[which deemed her a "half-Jew". During the prewar years, Haushofer was instrumental in linking Japan to the Axis powers, acting in accordance with the theories of his book Geopolitics of the Pacific Ocean.

After the plot to assassinate Hitler, Haushofer's son Albrecht was implicated and went into hiding. He was arrested on 7 December 1944 and put into the Moabite prison in Berlin. During the night of 22–23 April 1945, he and other prisoners, such as Klaus Bonhoeffer, were walked out of the prison by an SS squad and shot.

In the fall of 1945, Karl Haushofer was questioned by an interrogator for the Allied forces to determine whether the famous geographer should stand trial ; it was determined that his compromise with the régime did not implicate him in any war crimes and he was not charged by the war tribunal.

In 1946, on the night of March 1946, Karl Haushofer and his wife committed suicide. Was this suicide a result of the Haushofers realizing too late how deeply Karl had become an accomplice of a régime, the nature of the régime and what a contradiction this meant in their lives marked by Jewish roots and a more moderate German nationalism, a contradiction that lead their son to his death. Albrecht Haushofer himself may have provided us with the answer himself in one of his poems from prison:

After the plot to assassinate Hitler, Haushofer's son Albrecht was implicated and went into hiding. He was arrested on 7 December 1944 and put into the Moabite prison in Berlin. During the night of 22–23 April 1945, he and other prisoners, such as Klaus Bonhoeffer, were walked out of the prison by an SS squad and shot.

In the fall of 1945, Karl Haushofer was questioned by an interrogator for the Allied forces to determine whether the famous geographer should stand trial ; it was determined that his compromise with the régime did not implicate him in any war crimes and he was not charged by the war tribunal.

In 1946, on the night of March 1946, Karl Haushofer and his wife committed suicide. Was this suicide a result of the Haushofers realizing too late how deeply Karl had become an accomplice of a régime, the nature of the régime and what a contradiction this meant in their lives marked by Jewish roots and a more moderate German nationalism, a contradiction that lead their son to his death. Albrecht Haushofer himself may have provided us with the answer himself in one of his poems from prison:

|

Schuld

...schuldig bin ich Anders als Ihr denkt. Ich musste früher meine Pflicht erkennen; Ich musste schärfer Unheil Unheil nennen; Mein Urteil habe ich zu lang gelenkt... Ich habe gewarnt, Aber nicht genug, und klar; Und heute weiß ich, was ich schuldig war. |

Guilt

... I am guilty In a different way than you think. I should have recognized my duty earlier; I should have more severely called the calamity a calamity; My judgment, I reigned in for too long ... I had warned But not enough, nor clearly; And today I know what I was guilty of. |

NOTES

[i] Studies by Natter (2003), and the recent article by Barnes and Abrahamsson (2015) indicating a circulation of the magazine of 750,000 copies at its peak in 1933 must have been mistaken: a figure of this order is highly improbable.

[ii] However, this information must be taken with a certain reserve, because the first signature that we find of Albert Demangeon on the collection of the journal in the Geography Library, it is that affixed to the cover of N ° 2 of 1930, which also contains annotations. The same signature is present until volume 15, n ° 12 of 1938. For the numbers of the years 1920, we notice in particular the inscription on the cover: Per-All-15, which corresponds, in fact, to the periodical (German periodical number 15), attributed by the librarian in charge of periodicals of the time.

Bibliographical references:

Sources:

Jacques Ancel (1932), “Geopolitik and political geography”, in Revue d'Allemagne , p. 672-

693.

Jacques Ancel (1936), Geopolitics , Paris, Librairie Delagrave.

Jacques Ancel (1938), Geography of borders , Paris, Gallimard.

Albert Demangeon (1932), “Political geography”, Annales de Géographie , XLI, p. 22-31.

DOI: 10.3406 / geo.1932.11065

Georges Delamare (1938), “Television today and tomorrow”, in Zeitschrift für

Geopolitik , vol. 9, p. 673-676.

3 The state of collection of the Geography Library: vol. 4 no. 1 (1927); flight. 4 no. 3 (1927); flight. 4 no. 5

(1927); flight. 5 no. 1 (1928) -vol. 5 no. 2 (1928); flight. 5 no. 4 (1928); flight. 7 no. 2 (1930); flight. 7 no. 4 (1930); flight.

8 no. 5 (1931); flight. 8 no. 7 (1931); flight. 8 no. 11 (1931); flight. 9 no. 1 (1932) -vol. 9 no. 3 (1932); flight. 9 no. 6

(1932) -vol. 9 no. 12 (1932); flight. 10 no. 1 (1933) -vol. 11 no. 2 (1934); flight. 11 no. 4 (1934) -vol. 11 no. 12 (1934)

; flight. 14 no. 2 (1937) -vol. 14 no. 3 (1937); flight. 15 no. 12 (1938); flight. 18 no. 4 (1941); flight. 20 no. 2 (1943) -vol.

20 no. 3 (1943); flight. 20 no. 7 (1943); flight. 21 no. 1 (1944) -vol. 21 no. 2 (1944).

Karl Haushofer (1932), “Geopolitik in Abwehr und auf Wacht”, in Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ,

N ° 10, p. 591-594.

Karl Haushofer (1932), “Rückblick und Vorschau auf das geopolitische Kartenwesen”, in

Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , N ° 12, p. 735-745.

Karl Haushofer (1943), “Zwei Jahrzehnte Geopolitik”, in Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , N ° 8, p.

183-184.

Rupert von Schumacher (1934), “Zur Theorie der Raumdarstellung”, in Zeitschrift für

Geopolitik , N ° 10, p. 635-652.

Rupert von Schumacher (1937), “Theorie der geopolitischen Signatur”, in Zeitschrift für

Geopolitik , N ° 12, p. 247-265.

Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (1924-1944).

Secondary bibliography:

Trevor J. Barnes and Christian Abrahamsson (2015), “Tangled complicities and moral

struggles: the Haushofers, father and son, and the spaces of Nazi geopolitics ”, in Journal of

Historical Geography , vol. 47, p. 64-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2014.10.002

George Canguilhem (1994), Studies in history and philosophy of science , Paris, Vrin.

Frank Ebeling (1994), Geopolitik 1919-1945. Karl Haushofer und seine Raumwissenschaft ,

Berlin, Akademischer Verlag.

Karl-Heinz Harbeck (1963), Die Zeitschrift für Geopolitik 1924-1944 , doctoral thesis, Kiel,

Christian-Albrechts-Universität.

Guntrum Henrik Herb (1997), Under the Map of Germany. Nationalism and Propaganda

1918-1945 , London, New York, Routledge.

Holger H. Herwig (2016), The demon of geopolitics: How Karl Haushofer “educated” Hitler

and Hess , Lanham, MD, Rowman and Littlefield.

Henning Heske (1986), “German geographical research in the Nazi period. Happy

analysis of the major geography journals, 1925-1945 ”, in Political Geography Quarterly , vol.

5, n ° 3, p. 267-281.https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(86)90038-8

Walther Jantzen (1942), “Geopolitik im Kartenbild”, in Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , vol. 8, p.

353-358.

Richard Kleinschmager (1988), “Geography and ideology between two wars: the Zeitschrift

für Geopolitik 1924-1944 ”, in The Geographic Space , volume 17, n ° 1, p. 15-28. d oi

: 10.3406 / spgeo.1988.2719

Michel Korinman (1990), When Germany thought about the world. The rise and fall of a

geopolitics , Paris, Fayard.

Yves Lacoste (2012), “Geography, geopolitics and geographic reasoning”, in

Herodotus , 146-147 (3), p. 14-44. doi: 10.3917 / her.146.0014

Florian Louis (2014), The great theorists of geopolitics , Paris, University Press of

France.

David Thomas Murphy (2014), “Hitler's Geostrategist ?: The Myth of Karl Haushofer and the

'Institut für Geopolitik' ”, in Historian , vol. 76 (1), p. 1-25. doi: 10.1111 / hisn.12025

Wolfgang Natter (2003), “Geopolitics in Germany, 1919-1945: Karl Haushofer and the

Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ”, in John Agnew, Katharyne Mitchell and Gerard Toal (eds), The

Companion to Political Geography , Oxford, p. 187-203.

Wolfgang Natter (2004). "Umstrittene Konzept: Raum und Volk bei Karl Haushofer und in

der Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ”, in M. Middell, U. Sommer (ed.), Historische West- und

Ostforschung in Zentraleuropa zwischen dem Ersten und dem Zweiten Weltkrieg-

Verflechtung und Vergleich , Leipzig, Akademische Verlags-Anstalt, p. 1-28.

Gearóid Ó Tuathail (1996), Critical geopolitics. The politics of writing global space ,

Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Claude Raffestin, Dario Lopreno and Yvan Pasteur (1995), Geopolitics and history , Lausanne,

Ed. Payot, in particular chapter 3 of part II “From text to image”, p. 243-376.

NOTES

[i] Studies by Natter (2003), and the recent article by Barnes and Abrahamsson (2015) indicating a circulation of the magazine of 750,000 copies at its peak in 1933 must have been mistaken: a figure of this order is highly improbable.

[ii] However, this information must be taken with a certain reserve, because the first signature that we find of Albert Demangeon on the collection of the journal in the Geography Library, it is that affixed to the cover of N ° 2 of 1930, which also contains annotations. The same signature is present until volume 15, n ° 12 of 1938. For the numbers of the years 1920, we notice in particular the inscription on the cover: Per-All-15, which corresponds, in fact, to the periodical (German periodical number 15), attributed by the librarian in charge of periodicals of the time.

Bibliographical references:

Sources:

Jacques Ancel (1932), “Geopolitik and political geography”, in Revue d'Allemagne , p. 672-

693.

Jacques Ancel (1936), Geopolitics , Paris, Librairie Delagrave.

Jacques Ancel (1938), Geography of borders , Paris, Gallimard.

Albert Demangeon (1932), “Political geography”, Annales de Géographie , XLI, p. 22-31.

DOI: 10.3406 / geo.1932.11065

Georges Delamare (1938), “Television today and tomorrow”, in Zeitschrift für

Geopolitik , vol. 9, p. 673-676.

3 The state of collection of the Geography Library: vol. 4 no. 1 (1927); flight. 4 no. 3 (1927); flight. 4 no. 5

(1927); flight. 5 no. 1 (1928) -vol. 5 no. 2 (1928); flight. 5 no. 4 (1928); flight. 7 no. 2 (1930); flight. 7 no. 4 (1930); flight.

8 no. 5 (1931); flight. 8 no. 7 (1931); flight. 8 no. 11 (1931); flight. 9 no. 1 (1932) -vol. 9 no. 3 (1932); flight. 9 no. 6

(1932) -vol. 9 no. 12 (1932); flight. 10 no. 1 (1933) -vol. 11 no. 2 (1934); flight. 11 no. 4 (1934) -vol. 11 no. 12 (1934)

; flight. 14 no. 2 (1937) -vol. 14 no. 3 (1937); flight. 15 no. 12 (1938); flight. 18 no. 4 (1941); flight. 20 no. 2 (1943) -vol.

20 no. 3 (1943); flight. 20 no. 7 (1943); flight. 21 no. 1 (1944) -vol. 21 no. 2 (1944).

Karl Haushofer (1932), “Geopolitik in Abwehr und auf Wacht”, in Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ,

N ° 10, p. 591-594.

Karl Haushofer (1932), “Rückblick und Vorschau auf das geopolitische Kartenwesen”, in

Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , N ° 12, p. 735-745.

Karl Haushofer (1943), “Zwei Jahrzehnte Geopolitik”, in Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , N ° 8, p.

183-184.

Rupert von Schumacher (1934), “Zur Theorie der Raumdarstellung”, in Zeitschrift für

Geopolitik , N ° 10, p. 635-652.

Rupert von Schumacher (1937), “Theorie der geopolitischen Signatur”, in Zeitschrift für

Geopolitik , N ° 12, p. 247-265.

Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (1924-1944).

Secondary bibliography:

Trevor J. Barnes and Christian Abrahamsson (2015), “Tangled complicities and moral

struggles: the Haushofers, father and son, and the spaces of Nazi geopolitics ”, in Journal of

Historical Geography , vol. 47, p. 64-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2014.10.002

George Canguilhem (1994), Studies in history and philosophy of science , Paris, Vrin.

Frank Ebeling (1994), Geopolitik 1919-1945. Karl Haushofer und seine Raumwissenschaft ,

Berlin, Akademischer Verlag.

Karl-Heinz Harbeck (1963), Die Zeitschrift für Geopolitik 1924-1944 , doctoral thesis, Kiel,

Christian-Albrechts-Universität.

Guntrum Henrik Herb (1997), Under the Map of Germany. Nationalism and Propaganda

1918-1945 , London, New York, Routledge.

Holger H. Herwig (2016), The demon of geopolitics: How Karl Haushofer “educated” Hitler

and Hess , Lanham, MD, Rowman and Littlefield.

Henning Heske (1986), “German geographical research in the Nazi period. Happy

analysis of the major geography journals, 1925-1945 ”, in Political Geography Quarterly , vol.

5, n ° 3, p. 267-281.https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(86)90038-8

Walther Jantzen (1942), “Geopolitik im Kartenbild”, in Zeitschrift für Geopolitik , vol. 8, p.

353-358.

Richard Kleinschmager (1988), “Geography and ideology between two wars: the Zeitschrift

für Geopolitik 1924-1944 ”, in The Geographic Space , volume 17, n ° 1, p. 15-28. d oi

: 10.3406 / spgeo.1988.2719

Michel Korinman (1990), When Germany thought about the world. The rise and fall of a

geopolitics , Paris, Fayard.

Yves Lacoste (2012), “Geography, geopolitics and geographic reasoning”, in

Herodotus , 146-147 (3), p. 14-44. doi: 10.3917 / her.146.0014

Florian Louis (2014), The great theorists of geopolitics , Paris, University Press of

France.

David Thomas Murphy (2014), “Hitler's Geostrategist ?: The Myth of Karl Haushofer and the

'Institut für Geopolitik' ”, in Historian , vol. 76 (1), p. 1-25. doi: 10.1111 / hisn.12025

Wolfgang Natter (2003), “Geopolitics in Germany, 1919-1945: Karl Haushofer and the

Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ”, in John Agnew, Katharyne Mitchell and Gerard Toal (eds), The

Companion to Political Geography , Oxford, p. 187-203.

Wolfgang Natter (2004). "Umstrittene Konzept: Raum und Volk bei Karl Haushofer und in

der Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ”, in M. Middell, U. Sommer (ed.), Historische West- und

Ostforschung in Zentraleuropa zwischen dem Ersten und dem Zweiten Weltkrieg-

Verflechtung und Vergleich , Leipzig, Akademische Verlags-Anstalt, p. 1-28.

Gearóid Ó Tuathail (1996), Critical geopolitics. The politics of writing global space ,

Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Claude Raffestin, Dario Lopreno and Yvan Pasteur (1995), Geopolitics and history , Lausanne,

Ed. Payot, in particular chapter 3 of part II “From text to image”, p. 243-376.