Texts, photographs, links and any other content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.

100 Years Ago: the Battle of Verdun.

By David Vauclair.

David Vauclair, studied at McGill University and “Sciences Po” - Paris and teaches political science, in Paris, at the ILERI (the “Institut Libre d’Etudes en Relations Internationales” founded by René Cassin), the University of Paris-Sud and several other prestigious institutions. He is the author of many articles and books, including a recent monograph, co-written with Jane Weston Vauclair, on the Charlie Hebdo weekly satirical newspaper (De Charlie Hebdo à Charlie: Enjeux, histoire, perspectives), and Les religions d'Abraham : Judaïsme, christianisme et islam , a comparative study of the three large contemporary monotheistic religions prefaced by Odon Valet, one of Europe’s most renowned historians of religions.

“February 1916: throughout the month, fog, rain, and snow had covered the Champagne and Argonne fronts. On the night of the 19th, an eastern wind brought back stars and moonlight and, in the morning, cloudless blue skies. The next day, Monday the 21st, the earth began to shake. To the north, soldiers in their dugouts in the Aisne district could hear the dull roar and feel the rumble, more powerfully than when they had attacked in Artois region the year before. That night, they watched the southeastern horizon glow with multi-colored flashes, and the next day they learned that the Germans were attacking Verdun 60 miles away.” Thus writes historian Paul Jankowski about one of the bloodiest battles in history, on the first page of his Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War (Oxford University Press: New York, 2014). The image, a vivid one, shows not only a historic event but indeed a geographic one. David Vauclair, young proflific author who teaches geopolitics, shares with the readers of N&C – Nature & Cultures his comments on the battle that was so violent that its man-made eruptions reshaped the landscape of an entire region. Although not the most deadly battle in history, it is often perceived as such, and professor Vauclair discusses the reasons for this in terms of representation—a term dear to geographer and theorist Yves Lacoste (find out more about Yves Lacoste and French geography in this article by Juliet Falls).

“February 1916: throughout the month, fog, rain, and snow had covered the Champagne and Argonne fronts. On the night of the 19th, an eastern wind brought back stars and moonlight and, in the morning, cloudless blue skies. The next day, Monday the 21st, the earth began to shake. To the north, soldiers in their dugouts in the Aisne district could hear the dull roar and feel the rumble, more powerfully than when they had attacked in Artois region the year before. That night, they watched the southeastern horizon glow with multi-colored flashes, and the next day they learned that the Germans were attacking Verdun 60 miles away.” Thus writes historian Paul Jankowski about one of the bloodiest battles in history, on the first page of his Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War (Oxford University Press: New York, 2014). The image, a vivid one, shows not only a historic event but indeed a geographic one. David Vauclair, young proflific author who teaches geopolitics, shares with the readers of N&C – Nature & Cultures his comments on the battle that was so violent that its man-made eruptions reshaped the landscape of an entire region. Although not the most deadly battle in history, it is often perceived as such, and professor Vauclair discusses the reasons for this in terms of representation—a term dear to geographer and theorist Yves Lacoste (find out more about Yves Lacoste and French geography in this article by Juliet Falls).

"Imagine, if you can, a storm, a tempest, a downpour constantly rising where the raindrops are nothing but cobblestones, and where the hail is nothing but blocks of stone”. Wrote from the front, during the Battle of Verdun, a soldier, one of those “hairy ones” (“poilus” in French) -- a name given to the men in the trenches who rarely had a chance to shave or get a haircut living under the constant torrent of tons of shells quoted in Laurent Loiseau & Geraud Bénech, Carnets de Verdun). He was one of Lieutenant-Colonel Driant’s riflemens’ brigade, the first unit to bear the full shock of the German assault of February 21 1916. This was the first day of the centennial of a battle that we commemorate and which was to be the longest battle of the First World War, the battle of Verdun, lasting from February to December 1916—although some historians suggest that it was prolonged several months in 1917. The balance sheet is a record in the history of human folly: probably more than 750,000 casualties—over 300, 000 dead plus the wounded, plus the missing in action, Germans and French combined. The two armies poured over each other more than forty million shells, but tens of thousands of these never exploded as recalled Robert Zaretzky. "They dug into the slime of the battlefield where, as metal cicadas, they emerge from time to time in a murdereros surge." Every year after the armistice, for the past 100 years, the battle of Verdun, like the other battles of World War I in France and Belgium, continues to bring death.

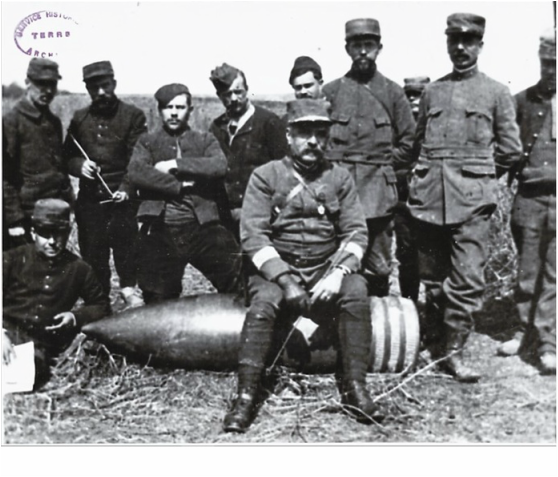

Lieutenant-Colonel Driant and his men. Émile Augustin Cyprien Driant (11 September 1855 – 22 February 1916) with his men. A science fiction writer, a journalist, and member of parliament, Driant became the first high-ranking casualty of the Battle of Verdun. There wold be many others. (photo from the archives of the Historical Service of the French armed forces)

It is agreed by most historians that the average number of shells falling on the battlefield is more than 6 shells per square meter (approximately one square yard). As concluded Alistair Horne in his now classic, Verdun, Perfect Body, it was the worst battle of a war among many candidates competing for that frightening title.

Yet, as noted by historian Paul Jankowski in Verdun, the place had no strategic importance. While the Germans, under the command of the German Chief of the General Staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn, had launched their offensive at the end of February, the French General Staff was ready to abandon Verdun in favor of an easier line to defend, several kilometers back of the fort. While the officers retreated in good order (and preparing to blow up fortifications and bridges), the French government ordered them to keep the line of defense all costs. Why ? To support the faltering morale of the French population. According to Jankowski (quoted by Robert Zaretzky in the Los Angeles Review of Books, "the politician's interest married the patriot's conscience." The motivations that drove Falkenhayn to double the lead in Verdun are even more elusive as to why the French decided to meet the challenge. Many historians, including Horne, say Verdun Falkenhayn chose because it was a national symbol that the French would defend stubbornly and that his strategy was summed up after disaster as "Ausblutung" – to “bleed” the enemy “to death”.

Yet, as noted by historian Paul Jankowski in Verdun, the place had no strategic importance. While the Germans, under the command of the German Chief of the General Staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn, had launched their offensive at the end of February, the French General Staff was ready to abandon Verdun in favor of an easier line to defend, several kilometers back of the fort. While the officers retreated in good order (and preparing to blow up fortifications and bridges), the French government ordered them to keep the line of defense all costs. Why ? To support the faltering morale of the French population. According to Jankowski (quoted by Robert Zaretzky in the Los Angeles Review of Books, "the politician's interest married the patriot's conscience." The motivations that drove Falkenhayn to double the lead in Verdun are even more elusive as to why the French decided to meet the challenge. Many historians, including Horne, say Verdun Falkenhayn chose because it was a national symbol that the French would defend stubbornly and that his strategy was summed up after disaster as "Ausblutung" – to “bleed” the enemy “to death”.

However, this argument does not resist scrutiny. Verdun became a national symbol only after the beginning of the battle. The city of Reims, gothic sanctuary of the kings of France, and only 100 kilometers (62 miles) away from Verdun, would have made a much better symbol. An eloquent detail, reminds Jankowski, is that not one French general ever evoked the iconic value of Fort Douaumont before the government made it into an emblem. The 300 days of Verdun (Jean-Pierre Tubergue, editor, Les 300 jours de Verdun, Service Historique de la Défense and Editions Italiques: Mantes-la-Jolie, 2006) pointed oout the following: although, after the war, Falkenhayn stated that "Ausblutung" had always been his goal, historians, despite all their efforts, have never found any documents from the archives to confirm his statements and none of the officers who served with him, ever remembered that the general had any such ambitions before the battle. In fact, Falkenhayn only reluctantly committed himself to the attack on Verdun, and that objective appears to have been little more than a preparatory operation launched to create greater opportunities elsewhere on the front. Yet, despite its lack of real strategic value, Verdun was turned into a pivot of conflict, the new Thermopylae where French soldiers, defending the ideals of 1789, rejected the Teutonic hordes and 1400 cannons of various calibers.

Documentary summarizing the battle of Verdun with archival films, from the daily newspaper Le Figaro (in French):

It may seem counterintuitive at first, but the battles of attrition like Verdun were less costly than the more traditional battles involving rapid movement that had marked the first year of the war. More remarkably, the shock of Verdun seems frankly benign, in proportion, compared to some of the clashes of the nineteenth century: the casualty rate in Waterloo was nearly 60%, compared to the relatively paltry figure of 16% achieved by Verdun (which lasted months, whereas Waterloo lasted only one day). The 1812 battle of Borodino, the one that the French call the “Moscowa” battle, killed at least 60, 000 soldiers in one day. But Russian historians have shown that that this number includes only the fatalities of the first day of battle and does not count the missing and those who died weeks or months later as shown in Tolstoy’s War and Peace in the chapter’s portrayal of Prince Andrey’s slow and quiet agony. The horrors of the 1859 battle depicted by Henri Dunant in his landmark Memory of Solferino provoked such a public reaction that it pioneered the founding of the Red Cross, and with the signing of the Geneva Convention, the political culture of human rights. The horrors of the battle (30, 000 casualties), relayed by growing literacy and consequent accessibility to the press and to world news for the masses, created a sort of a dialectic confrontation between the rise of violence on an industrial scale and the public’s reaction to it. Verdun was not the deadliest of the episodes of World War I; the attacks on Champagne and on the Somme were to prove far more murderous. But, it is consistent with a perception of the escalation of the means of warfare on the eve of and during the industrial revolution. The difference with the wars of earlier generations was the increase of propaganda and of the means of mass communication with the triumph of easily printable photos (some already in color) and cinema and their effect on the perception of war by the by the masses. The circulation of information was exponential to the escalation of the means of destruction. Thus, as pointed out by all the literature on the subject, the episode of Verdun became a phenomenon. It became the black hole of the conflict in French imagination. Its symbolic mass sucked into its center—into its singularity—the entire significance of the war.

The horror of this battle which seemed eternal was unspeakable. Imagine the heat of a cloudless silence, compact and sticky mud, infested with lice and rats, and downpour of tons of sharp steel tirelessly massacring men, mutilating corpses and exhuming the sickening smell of the putrid corpses and of the feces of living. Fear is omnipresent—the fear of being buried alive, to be forgotten, to be decimated by bullets or by gases, or to lose a limb before losing one’s mind. Imagine hunger, thirst, pain and intense feelings of isolation and loneliness, as it existed perhaps never before or elsewhere.

Why did the soldiers nevertheless accept this universe? Why did they accept to serve as cannon fodder when they clearly saw through the official justifications for the bloodshed, while there seemed to be no end in sight, as the only winner was the battle itself? Jankowski first recalls that mutinies occured, but according to him, neither military coercion nor fear of punishment is what kept the men in the trenches. Neither was it patriotism or the republican spirit, even if Jankowski suggests that many soldiers absorbed the dehumanizing propaganda targeting "the Krauts". No, what drove so many men to continue—under the logic of Beckett "I can not continue. I will continue "—were the links that bound the raggedy soldiers to their family and to their comrades. The most amazing statistic of this war, and not only of Verdun, may be the following: over ten billion letters were exchanged between the front and the rear. As reported long ago by Paul Fussell in The Great War and Modern Memory or more recently by Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau in Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Quelle histoire. Un récit de filiation (1914-2014), Paris, EHESS-Gallimard-Seuil, 2013, it was a literary war, a war where the epistolary relationship reminded the soldiers of a reason for which they fought. As concludes Jankowski, it was a sort of feeling of duty which arose from the depths of themselves, awakened by a sense of allegiance rather than hostility, by love of country rather than by animosity. " Facing death man is less alone if hell is a shared experience.

“When in my teens I hiked on the trails crossing the battlefields of Eastern France, between 1972 and 1976”, recalls Nature & Cultures Oleg Kobtzeff, founding publisher, “you could find an impressive amount of exploded or unexploded ammunition. When, as 14 or 15 year-old irresponsible kids we went slightly off the beaten tracks into the underbrush, we would almost always find shrapnel, shells and even hand grenades that were perfectly intact, only muddy. In these patches of woods that remained unplowed after the war, the gruesome artifacts were as common as beer cans scattered along a rural highway. How, after playing with those artifacts, we did not become victims ourselves of World War I, almost six decades after the peace was signed, is a miracle.” Earlier, in June of 1965, Kobtzeff, as a little boy, was taken accompanied his father on a tour of the most renowned landmarks, Verdun. We arrived at the Fort Douamont that had been fiercely disputed during the battle, recalls Kobtzeff. “Almost 50 years after the end of the battle, the landscape all around us was lunar: only sand-colored mud and craters form shelling extending for miles and miles.”