"Lavapiés" by Katy Dycus; photos by Rubén González

Texts, photographs, links and any other content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.

|

Native Lavapiés inhabitant Rubén González (right) says of his "barrio" (quarter) of Madrid that it has "an artistic spirit. There are musicians, writers, actors, photographers, designers, people who work in TV. At the same time, it’s a barrio with a very strong political commitment, and a lot of social compromise.” "Manos a la Obra" (Which means "Let's do it!" or "Let's go!"), one of many murals for which Lavapiés has a reputation, sounds like a perfect invitation. Let Rubén's photographs and Katy Dycus' text take you on a tour of what both N&C contributors call a beautiful mosaic.

(this is part of a dyptich also featuring the cosmopolitan 7th district of Paris) |

|

The café El Dinosaurio Todavia Estaba Alli was a further walk than I had anticipated. The chilly air prompted me to wrap my plaid, woolen scarf around my neck multiple times. I peered up into a jet-black sky searching for solace among the stars but not finding any. Rows of tenements literally blocked them out.

I rehearsed my poem out loud until I reached the demarcation marking off Calle Lavapiés to the left. I had another 30 minutes to go along the barrio’s major artery, which meant I could walk off all of this nervous energy with no disturbance. That is, until someone stepped forward whistling and offered to sell me hash. “No,” I said, smiling. I walked on, knowing I had offended no one, knowing I wasn’t being followed. Once I stepped foot inside the dimly lit gastropub, I was surrounded by cut-outs of the Brontosaurus hanging from the ceiling. They seemed to dance, lifelike. As I made my way through a noisy crowd, I thought about how, in that short walk from the subway, I had cut through a slice of human life. In this seedy-yet-fun-loving life on the street, a mixture of ethnicities, sexual orientations, languages, religions, and politics glide past each other all the time. My friend once spotted a same sex couple holding hands and passing someone in Muslim prayer robes on the way to Friday prayers here—all against the backdrop of an anarchofeminist poster.

|

A shocking mix of cultures

|

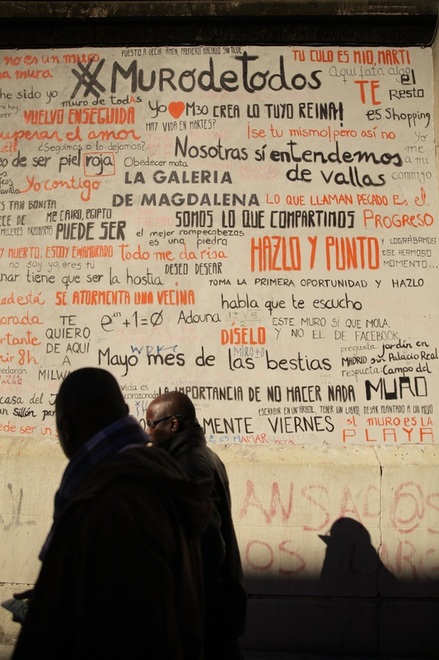

Lavapiés which is characterized by its extremely diverse population and mural art also features this "Muro de Todos" (above) the name of which means "Wall for All", and where anyone can scribble down a phrase like "Yo contigo" (I with you) or "Somos lo que compartimos" (We are what we share).

|

Lavapiés is a neighborhood off the beaten track, with a shocking mix of cultures noticeably absent from the rest of the city. A large immigrant population has made Madrid the most culturally diverse city in Spain, with much of this population concentrated in Lavapiés. “SOS Racismo Madrid” (www.sosracismomadrid.es) is a non-profit based here. Run exclusively by volunteers and operating since 1992, the center fights against all forms of discrimination and segregation on the basis of skin color, ethnic origin, religious and cultural identity. Its field of action is the Community of Madrid, and it coordinates with other associations to ensure its impact is felt at both the national and international levels. The center treats racism and xenophobia like the diseases they are, investigating these issues for their prevention and eradication.

But Lavapiés wasn’t always so inclusive. The barrio was the Jewish and Moorish quarter outside the city walls until they were forced into exile or conversion in 1492 under the Alhambra Decree. The name Lavapiés literally translates to “wash feet” and refers to the ritual of the washing of feet before entering a temple, possibly in the fountain of Plaza de Lavapiés, which no longer exists. The Alhambra Decree was revoked only in December 1968 following the Second Vatican Council. In 2014, the Spanish government passed a law allowing dual citizenship to those descendents of Jews expelled from Spain under the edict. In the shadows of such a past, Lavapiés is made up of individuals whose lives have been, to varying degree, threatened by intolerance—from mainstream culture, Church or State. Citizens of Lavapiés, today, tend to value tolerance and often in the form of artistic expression, the freedom of mind-body-spirit in action. An artistic expression sometimes registered in the spoken word.

|

"Upon awakening, the dinosaur was still there"

Once I settled into place at El Dinosaurio Todavia Estaba Alli—Tinto de verano in hand—I registered a noticeable shift. Just moments ago, my veins were throbbing with the energy supplied by vibrant city streets. Now, they pulsated to the gentler rhythm of literary types who had gathered to recite original writings before an audience. The Madrid Writer’s Club hosts open mics a few times a year, and tonight’s event was held here, in a place named after Augosto Monterroso’s very short story:

Cuando despertó, el dinosaurio todavía estaba allí. Upon awakening, the dinosaur was still there.

I’m not sure what this means, and that bothers me. Upon awakening from a dream, the dream had become the reality, or the dream becomes part of reality? Reality contains the dream? This ambiguity set the tone for the evening. Lights were dimmed for intimacy as the little space grew dense. Everyone sat around a bit tipsy, generously tossing out accolades. It was so cozy I never wanted to leave. Writers from all over Europe and North America—many of them English speakers—read from their journals, inviting us to tour the landscapes of their imaginations. My poem about a girl who drinks in the moon through her tea cup received cheerful applause, but then so did everyone else’s stories. The audience responded to me in the same way they had to the man who described an awkward episode of sexual arousal, to the woman who passed around peanuts while reciting an ode to the plant kingdom.

Cuando despertó, el dinosaurio todavía estaba allí. Upon awakening, the dinosaur was still there.

I’m not sure what this means, and that bothers me. Upon awakening from a dream, the dream had become the reality, or the dream becomes part of reality? Reality contains the dream? This ambiguity set the tone for the evening. Lights were dimmed for intimacy as the little space grew dense. Everyone sat around a bit tipsy, generously tossing out accolades. It was so cozy I never wanted to leave. Writers from all over Europe and North America—many of them English speakers—read from their journals, inviting us to tour the landscapes of their imaginations. My poem about a girl who drinks in the moon through her tea cup received cheerful applause, but then so did everyone else’s stories. The audience responded to me in the same way they had to the man who described an awkward episode of sexual arousal, to the woman who passed around peanuts while reciting an ode to the plant kingdom.

|

There was a reason the Madrid Writer’s Club chose to host here in the heart of Lavapiés, its bohemian spirit wafting through the streets like the strong scent of chicken biryani. This is, after all, a multiethnic and counter-cultural barrio, one with artistic appeal laid out in its topography. From Plaza de Lavapiés, you can walk uphill towards Plaza de Tirso de Molina, named after the Golden Age playwright who created the original antics of Don Juan in “El Burlador de Sevilla.” This square belongs to no one neighborhood. Lavapiés lies to the south, Sol to the north, Huertas to the east, and La Latina to the west. Once a slightly dangerous crossroads, it’s now marked by outdoor cafés—where you can partake in one of Madrid’s great pleasures, “las terrazas”—a flower market and playground. From Tirso de Molina, you can walk to the art nouveau Cine Doré, on Calle Santa Isabel. As the film theater of the Spanish Filmoteca, its three screens show films every day in their original language. There might be a Woody Allen week, followed by a week of films focused on Japanese cinema, but no matter the film, this Lavapiés landmark charges 2.50 euro. An accessibility to the secret pearls of cinema speaks to the values that define Lavapiés. It invites those with perhaps few resources but big ideas.

|

Rubén González, a telecommunications professional and aspring indie filmmaker from Asturias, says that he’s continually inspired by his creative environment. “Lavapiés has an artistic spirit. There are musicians, writers, actors, photographers, designers, people who work in TV. At the same time, it’s a barrio with a very strong political commitment, and a lot of social compromise.” He thinks of the barrio as a beautiful mosaic, where there is not just one Lavapiés. “Historically, it was the old Jewish neighborhood. In these days, it’s the most multicultural area in Spain. There are immigrants from all around the world. It’s kind of a little UN,” he says. This ethnic diversity lends itself well to artistic diversity.

Unofficial strains of artistry wind through the landscape of Lavapiés, which brings you up and down steep hills in the manner of a small San Francisco. Apart from the intimacy of micro-theater crowds gathered in friends’ apartments to fringe meetings huddled in abandoned or unlicensed premises along Calle Ave María, there are spots where music literally spills out onto the streets. Maloka, for instance, features talented Brazilian reggae singers, whose melodies and drum beats pitch the perfect backdrop to bottomless mojitos. “Where do you wanna go tonight, Katy?” A friend might ask. “Uh, do you have to ask?” Never have I been in such a free-flowing environment—except for maybe Ecstatic Dance in the San Francisco Bay Area. You’re free to dance, do cartwheels, kiss strangers, move to whatever beat moves you. “Bebê não chorar!” (Baby, don’t cry!) one of the musicians shouts, his dreadlocks carrying a life force independent from him. Maloka just couldn’t exist in any other barrio, not even in the Malasaña neighborhood.

In the 70s and 80s, Malasaña led the countercultural movement—La Movida—that took place in Madrid during the Spanish transition after Francisco Franco’s death in 1975. It represented the resurrection of the Spanish economy as well as the emergence of a new national identity. Characterized by freedom of expression, La Movida did away with taboos imposed by the Franco regime and encouraged the use of recreational drugs. But these days, Lavapiés exhibits the spirit of La Movida, even moreso. Malasaña has evolved into a refuge for hipsters, with more a concern for aesthetics over substance. Ali Morgan, our American expat, was living in “Malasaña, a trendy neighborhood full of English-speaking expats” and decided she wanted a change. “Lavapiés is a more diverse neighborhood,” she says. “I thought I could have a more authentic Spanish experience here. An added bonus is that the cost of rent is lower in Lavapiés than in Malasaña. My old apartment was dark, cramped, and moldy. Now, my rent is the same, but my apartment is bright and airy with three balconies and lots of bookshelves.”

|

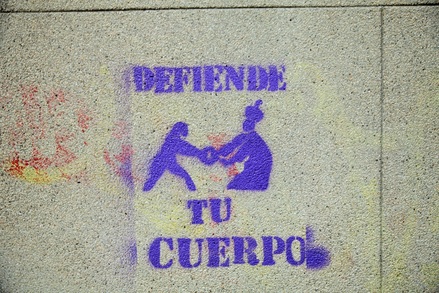

"Defend your body". The mural feature (above) symbolically representing the power struggle between citizens and institutions of authority, is much more than than a simple graffiti. this stenciled print is an example of political folk art reminiscent, in style and content, of the protesting students' posters during the May 1968 movement in Paris.

|

Street artLavapiés compares well to Williamsburg, a neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York, which has earned its #1 spot on the world’s most hipster cities. Free walking tours in and around Bushwick focus on its plentiful graffiti art, and Instagram meet-ups—where everyone’s an amateur photographer with a DSLR camera—are regular occurrences. But the graffiti art of Lavapiés emerges from a different mentality. It speaks of an attitude expressing revolutionary or anti-Franco sentiment. One notable mural features a headless family surrounded by skulls, with the caption: “Contra la impunidad de los crimenes franquista” (Against impunity for the crimes under Franco’s regime). It points to the countless tragedies inflicted by the evils of fascism. Another gripping image features a power struggle between citizen and authority figure, framed by the words: “Defiende tu cuerpo” (Defend your body). This simple image empowers the viewer while recognizing the need to defend one’s self against institutional force.

|

(Understanding political agendas here requires a knowledge of modern Spanish history, beginning right before the Second World War. The first key event occurred in May 1936, when the Popular Front (a coalition of Socialists and Communists) defeated the National Front, electing Manuel Azaña president of the Spanish Republic. This was a short-lived victory. The government did not stay in power long due to conflicting ideological views, but the party’s one uniting feature was the desire to vanquish fascism. On July 17 of that year, Francisco Franco and other ultra conservative generals staged a coup d'état, which ignited the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and initiated a bloody period of “White Terror,” which lasted until 1945. The main goal of White Terror was to terrify the civil population who opposed the coup, to eliminate supporters of the Second Spanish Republic and militants of the leftist parties. Nationalist authorities, under Franco’s leadership, wanted to eradicate any trace of “leftism” in Spain through violence.

The notion of a “limpieza” (cleansing) was an essential component of the right-wing rebel strategy. With the bombing of the Basque country village, Guernica—made famous by Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), the Spanish civil war was brought to the world’s attention. The aerial bombing, ordered by the Spanish nationalist government was carried out by its allies, Nazi Germany whose air force sent its Condor Legion, and Mussolini's Italy who sent Aviazione Legionaria. Their bombing of Guernica is considered one of the first raids on a defenseless civilian population by a modern air force. In addition, mass killings of the Loyalist and Popular Front parties (including liberals, Socialists, anarchists, Stalinists and intellectuals) occurred from the beginning of the Spanish civil war and lasted for six years. Because of the tens of thousands of deaths, some historians consider White Terror a genocide. Other historians would prefer the term "democide" since the targets were not massacred specifically for belonging to any specific ethnicity or other group as defined by the UN definition of "genocide". The result was the same.

A headless family surrounded by skulls, with the caption “Contra la impunidad de los crimenes franquista” (Against impunity for the franquist crimes) denounces the countless tragedies perpetrated under Franco’s regime that still, according to the street artist who painted this monumental mural (above), shows how the tragic past of Spain and Madrid is still a subject of present debate in highly politicized Lavapiés.

Initially, the Spanish Republican Army reorganized itself to successfully defeat Franco’s troops in cities like Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao, and Valencia. But by 1939, Franco had exhausted the Republican forces; their defeat meant his rule. He ran Spain as a dictatorship until his death in 1975. In many ways, fascist and communist movements—both originating in twentieth century Europe—had opposing ideologies, but both ended up being repressive political systems based on the control of a single leader. While communism focuses on a theory of economic equality, fascism glorifies the state through violence and conquest; neither regime values individual choice as much as society as a whole. Standing as an anti-war symbol, Picasso’s Guernica did not land on Spanish soil until September 1981. It was Picasso’s desire that the painting should not enter Spain until liberty and democracy had been firmly established there. Today, Guernica permanently resides on the second floor of Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofía, just a short walk from the Lavapiés metro station.

Guernica embodies the political mentality of democracy and liberalism. While an assortment of political attitudes remain scattered across Spain, Lavapiés represents one cohesive unit that is most assuredly for the people and by the people. It honors all citizens as equal and deserving of basic human rights and freedom of speech. It is a society glowing with the freedom to choose, even if that means choosing a life fundamentally separate from State or Church. But if we’re being honest, Lavapiés seems freer than a free democracy. It’s a place where almost anything goes. Life and law seem loose here, but individuals, for the most part, coexist without issue. There is a wall of graffiti art consisting only of words: “Muro de Todos” (Wall for All), where anyone can scribble down a phrase. On this wall there is the line “Yo contigo” (I with you) and “Somos lo que compartimos” (We are what we share). Many residing in Lavapiés have either escaped oppression, or they sympathize with those who have. As a result, the prevailing attitude is one of peace and mutual respect.

This peace transcends the constructed barriers of difference, and is manifest in graffiti portraits of love—“ Lovepiés”—in reflections of nature and bold blendings of color synonymous with harmony. Whatever the subject matter, graffiti artists in Lavapiés veer towards politically minded leftism. Street art is a visible reminder of the neighborhood’s history, presenting a defiant stance against those that threaten human dignity and freedom. It speaks to all who will listen and encourages all to speak. A powerful response to violence, a cry of vengeance, a reminder of past wrongs and past rights, a voice for the future, the dream of liberalism, the hand of peace, and an invitation to love. Lavapiés teaches us to walk with eyes wide open and wears its graffiti art as badges of truth. As in the turning of a kaleidoscope, an infinite variety of colors and scenes appear, and you get to decide what to do with it.

I remember the first time I visited Lavapiés. It was to attend a book signing for Maestros del Periodismo, a collection of essays written by two Spanish journalists, Manuel Jabois and Eduardo del Campo, who have juggled a series of controversial topics from Catalonia’s fight for independence to women’s rights in Muslim states. Through leveraging controversy and debate La Fugitiva has become a center of intellectual thought and exchange within Lavapiés, the barrio that serves as an intellectual center within the Capital city of Spain. Here we see a willingness to go against something, to become anti-something: anti-mainstream, anti-government, anti-religion, anti-establishment. An inscription on a nearby fountain in Plaza de Cabestreros, for instance, serves two functions: it is a monument to the Spanish Republic in Madrid just as much as it is anti-Franco.

Lavapiés was Madrid’s working class neighborhood for hundreds of years and had largely fallen into decay until artists and immigrants began filling its abandoned buildings in the 80s and 90s. At that point, it started filling its lungs with fresh oxygen. In terms of timing, it’s as though the barrio could not become fully alive until Franco’s regime was fully dead. By the end of the twentieth century, a program of urban renewal was instituted and has been moving forward ever since. Neighborhoods like Lavapiés typically experience the same fate. Initially, the inexpensive cost of living attracts immigrants, the downtrodden, and counter-culture types. The diversity and color they bring starts attracting money and rents skyrocket. Those who gave the area its buzz in the first place are forced to move out, and then comes your neighborhood Starbucks. Thus begins the inevitable process of gentrification.

“The only highly cosmopolitan place to live in the city”

But for now, Lavapiés retains its edginess and continues to provide a way of life for all: starving artists, immigrants, broke students, society’s misfits, young entrepreneurs, the occasional—ok, not so occasional—drug dealer. Jonathan Adams, a Canadian and sole proprietor of “Hiking in the Community of Madrid,” says that rent is “reasonable for a place where a lot of people want to live. But if it increases then that will start to push out certain people and change the atmosphere of the neighborhood.” In the two and a half years he’s lived here, he has noticed other young Europeans and North Americans. “This is really the only highly cosmopolitan place to live in the city, plus it has a neighbourly environment. And if perhaps not everybody mixes evenly, there is at least no problem between groups of people within Lavapiés.” He says that while it is a very attractive place to live for some, “there are others who have never been here, do not visit and do not want to visit. They are afraid, either of a reputation long since left behind or more explicitly not fans of visible minorities in Spain. This extends to the police as well, who have a heavier presence. Other city services like street cleaning are much less frequent than in richer neighborhoods.”

Many Spaniards avoid Lavapiés, bypassing its thoroughfares altogether, but others are not even aware it exists. One weekend I met a British guy on one of Jonathan’s hikes in Manzanares el Real. On our return to the city, he showed me his Madrid map on the subway. “Look, it’s clearly missing. There’s this gaping hole where Lavapiés should be.” What caused the omission? Perhaps Lavapiés didn’t represent someone’s notion of what constitutes the real Madrid, or the real Spain for that matter. Not much, if anything, is mentioned about Lavapiés in Spain guidebooks either. From Rick Steves’ Spain to Lonely Planet, there is hardly a mention of this unique neighborhood besides El Rastro, the Sunday morning ritual which has easily become a Madrid institution in its own right. The enormous flea market winds down Calle de la Ribera de Curtidores and through a maze of streets taking you through a maze of goods: cheap clothes, old flamenco records, even older photos of Madrid, grungy T-shirts, luggage, and random electronics. The limitless offerings at El Rastro reflect the infinite variety that is Lavapiés. The neighborhood is like a person with multiple identities, offering a case for endless psychology study.

In most tourist publications about Madrid, there is hardly any mention of the unique neighborhood which is Lavapiés. Escaping obscurity is El Rastro, the flea market of Lavapiés, a Sunday morning ritual which has easily become a Madrid institution in its own right. The enormous flea market winds down Calle de la Ribera de Curtidores and through a maze of streets taking you through a maze of goods.

The truth is, Lavapiés is sort of Dickensian, full of those larger-than-life characters that work well within the confines of a novel like Sketches by Boz. If Dickens were alive today and roaming the streets of Lavapiés instead of those of London, he could easily create entertaining sketches concerning its people and scenes without having to fictionalize a thing. The story tells itself. There are those characters lurking in the alleyways, sheltered by the cover of darkness, but Lavapiés doesn’t seek to hide its problems or struggles. There is nothing pretentious about it. Often, it presents the situation of making it against real odds.

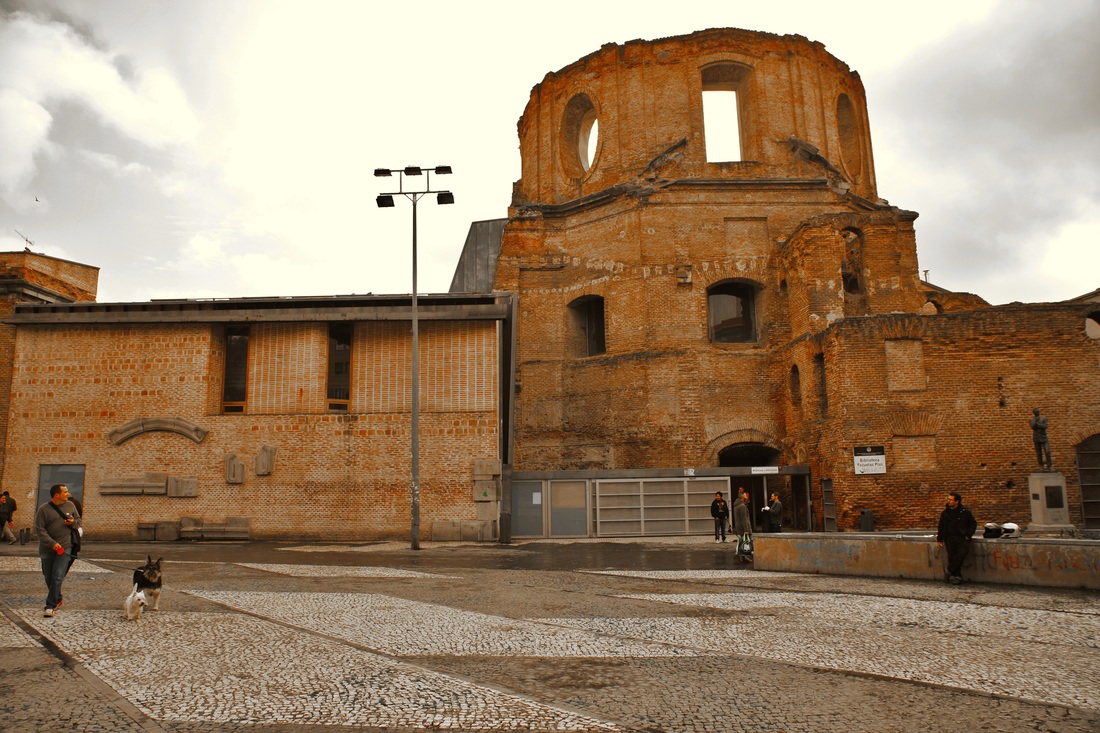

Ramizul Kabir, a Bangladeshi immigrant in his sixties, runs a grocery store in Lavapiés called Alimentación Frutería. It is estimated that 60% of Madrid’s population is of foreign origin. “We live peacefully here,” he says. “But cost of living still quite high.” Kabir’s family remains in Bangladesh. He sends part of his pay check home each month to support them, but it is not enough. His dream hasn’t been fully realized, but he works hard, and that’s all anyone can be expected to do. Near Kabir’s store stand the ruins of Escuelas Pías, a religious school, which was neglected for many years after it was burned down by the anti-Catholic, radical left that supported the Popular Front in 1936. Only in 2002 were the ruins converted into a university library. It serves as a reminder of how the past can be powerfully reimagined. Once the site of destruction, the library now provides citizens with unlimited access to knowledge. A shelter for stories and voices, the library and Lavapiés itself circulate notions of creative resolution.

The ruins of Escuelas Pías, a religious school, which were neglected for many years after the school was burned down by the anti-Catholic, radical left that supported the Popular Front in 1936. In 2002 the ruins were converted into a university library.

When my friends asked me where I wanted to spend my last night in Spain, it was a no brainer. “Definitely Lavapiés,” I said. The four of us bonded over cañas in La Playa de Lavapiés—a popular tapas bar—followed by dessert at La Infinita, the book café I’d been wanting to visit. Then we roamed the neighborhood’s streets, directionless and content. There were a few South American men gathered around a bench, singing. I could see their breaths spiraling into the wintry night. Their leader strummed his guitar, his voice in the likeness of Joaquín Sabina. A couple of his friends drunkenly approached us. One extended his hand in an invitation to dance, or at least join in the sing-along. The other, uninhibited, took my Spanish friend aside and shared a sad tale about the woman who left him. I watched as it fed into the collective imagination that blurs the lines of politics, art, work, play.