Texts, photographs, links and any other content appearing on Nature & Cultures should not be construed as endorsement by The American University of Paris of organizations, entities, views or any other feature. Individuals are solely responsible for the content they view or post.

Do not miss these feature stories in this Issue 5 (Winter-Spring 2021) of N&C Nature & Cultures:

"Thalassa's" Georges Pernoud (1947 - 2021)” a tribute to one of France's icons of travel journalism; “Borders and identities - Let us change our way of thinking” by Dr. by Katja Banik; "An emblematic geopolitical journal in Germany: the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (1924-1944) and its newsworthiness"

by Prof. Goran Sekulovski; "The Chernobyl effect: did ecological damage bring down the Soviet-model régimes of Central and Eastern Europe?" by Colin Hardage; "The Chinese Communist Party and the Environment" by Caleb Lemke. Plus our permanent features: The Nature & Cultures electronic library, and our mini-encyclopedia of constitutional systems country by country: The Comparative Government Project

"Thalassa's" Georges Pernoud (1947 - 2021)” a tribute to one of France's icons of travel journalism; “Borders and identities - Let us change our way of thinking” by Dr. by Katja Banik; "An emblematic geopolitical journal in Germany: the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (1924-1944) and its newsworthiness"

by Prof. Goran Sekulovski; "The Chernobyl effect: did ecological damage bring down the Soviet-model régimes of Central and Eastern Europe?" by Colin Hardage; "The Chinese Communist Party and the Environment" by Caleb Lemke. Plus our permanent features: The Nature & Cultures electronic library, and our mini-encyclopedia of constitutional systems country by country: The Comparative Government Project

“We should not be intoxicated with our victory over nature too much. For every victory, nature retaliates.” – Friedrich Engels

ithin half a century, China has pulled off the most astounding development feats in history, turning the nation from a poor, underdeveloped, pariah government into one of the largest economies in the world, and pulling hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in the process. This growth and the nation’s relatively new political stability has given rise to a huge middle class, and has been used by the governing Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as a source of legitimacy for their continued rule. As astounding as this progress is though, the rapid development has come at a massive cost to the natural environment in China. Water and air pollution are rampant, deforestation and desertification eat away at Chinese resources and the current COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to the CCP’s poor treatment of biodiversity and wildlife.[1] The consequences of the widespread environmental degradation across China has been impossible to miss. Environmental awareness among the general population of China has been growing, and so has outrage over the worsening quality of life caused by environmental degradation. Rather than simply accepting this reality, the Chinese public has begun to vocally express anger over these issues; campaigns, protests and even riots have broken out as public anger at the government builds, leading to the environment becoming the leading cause of unrest in China in 2013.[2] The unrest caused by the CCP’s disregard for the environment in pursuit of maximizing economic growth has created one of the greatest threats to their rule in China.

|

he context of environmental history is important to understand the relevance of actions taken today. Historically, Maohong notes that there has always been an “element of respect for nature in Chinese traditional culture,”[3] but that this is not the first time that China has faced serious environmental issues. An early example of these environmental problems was the erosion, flooding and deterioration of the Loess Plateau. Extensive agriculture and irrigation took a toll on the area but forced a new environmental consciousness as residents had to shift to intensive agriculture and plant a wider variety of plants to ease erosion.[4] As early forms of urbanization occurred in China, local governments had to pay attention to the environment because of the new issues of resource scarcity in cities. When the government was perceived as failing to care for the environment, it often had severe consequences from the public. “Among the Chinese dynasties, the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming were overthrown following popular revolt that developed alongside environmental problems: poor harvest, locust attacks, droughts and major floods leading to famines.”[5] This also created one of the enduring fears of the regime – widespread unrest from an environmental disaster that they either caused or were unable to respond to competently.[6]

|

|

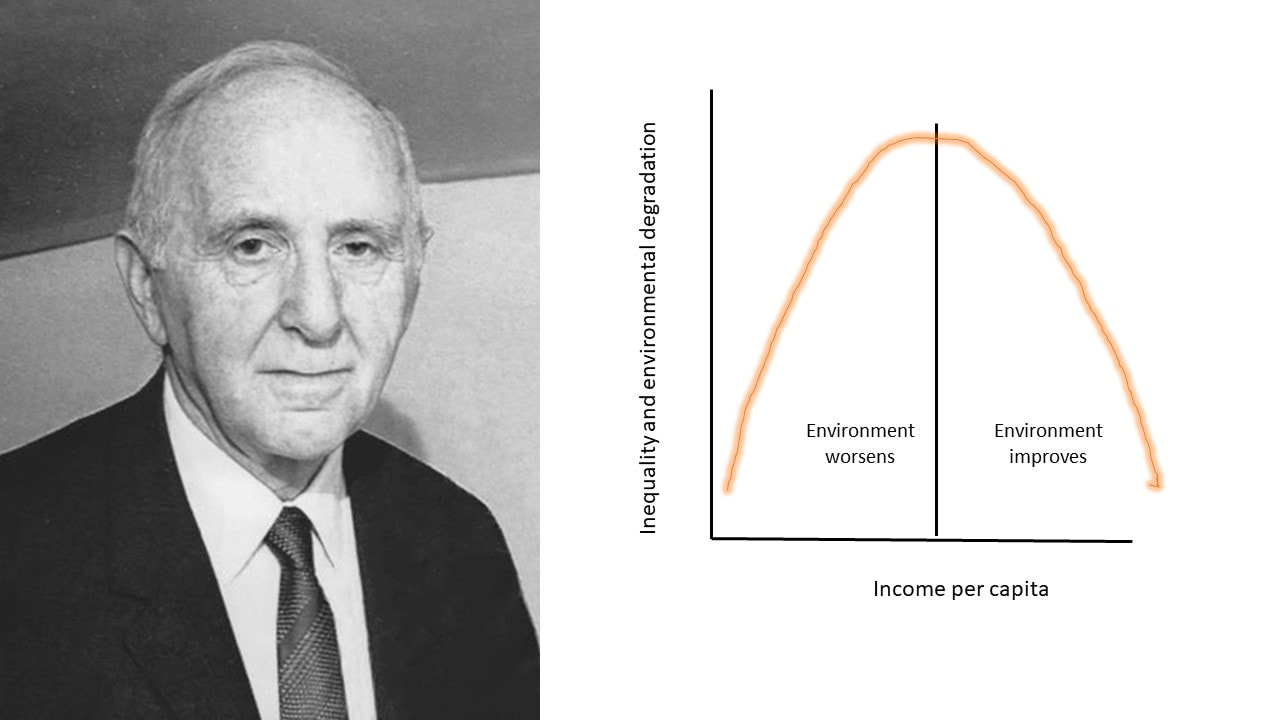

The most important leader for China’s environment in recent years has been Deng Xiaoping. Beginning in the late 1970’s, he began making strides to reform the Chinese economy, to bring it to the level of other industrial powers as quickly as possible. To do this quickly, leadership understood that there would be a high environmental cost. To justify this, leaders began to adopt a new theory known as the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis, which “asserts that environmental degradation increases in the early stages of economic development (as indicated in higher emissions per capita) until the process reaches a turning point or threshold at a higher level of economic development. Thereafter the overall levels of degradation will gradually fall and stabilize at a relatively low level.”[7] In other words, the EKC hypothesis is the belief that for development to occur, and to occur quickly, there will be no way around degradation. After enough time passes, an educated and environmentally conscious public and a healthy self-sufficient economy will develop, prompting a gradual tapering off of environmental degradation. Maohong sums up the attitudes of CCP leadership in this period, saying they “conducted socialist construction… which resulted in intensive industrialization of resources in industry and an attitude of 'man must conquer the heavens’… This led to a kind of destruction that had no regard for the laws of nature and remade nature at will. The spirit of the times… over-exploit[ed] the environment. The final result was massive environmental damage in China.”[8]

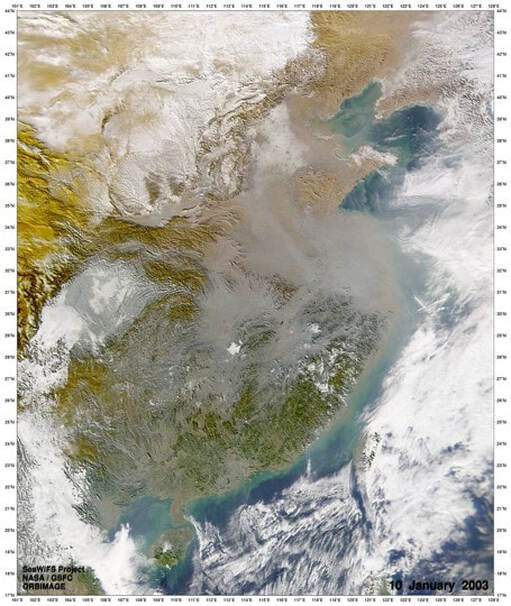

Now, however, the environmental degradation in China has become so bad that the nation is infamous for its poor environ- |

|

mental status. In particular, air pollution in Chinese cities is unparalleled around the world, with China becoming the number one source of greenhouse gases in 2013.[9] In Beijing alone, fifteen known carcinogens are regularly found in the air – all fifteen were found to be fourteen times over the legal limit. Only one-third of Chinese cities can meet the government’s own air standards,[10] and smog warnings and severity levels have become a part of the weather report on Chinese news. In addition, air pollution has been linked to causing the deaths of over a million Chinese citizens every year; over the last 30 years, lung cancer rates are believed to have risen 465%.[11] Water pollution also cannot be overlooked, with Sinologist Elizabeth Economy even claiming that “No resource is more important to China’s continued economic growth or more worrisome to China’s leaders than water.”[12] A 2013 report indicated that almost 90% of China’s groundwater was severely polluted, and that one-fourth of the water in Chinese rivers is too polluted for even agricultural and industrial use. With Chinese officials acknowledging that 8-15% of China’s GDP is lost as a consequence of pollution, it is painfully clear just how bad the situation has become.[13] The semi-regular environmental and pollution scandals that spark outrage across the country are quite noteworthy as well. While the world is currently consumed by COVID-19, a consequence of the nation’s poor environmental controls, another very memorable example of these scandals comes in March of 2013. Pig farmers along the Huangpu River had a horrible incident where almost all of their herds became diseased and infected, forcing the farmers to slaughter the herds; rather than incinerate or bury them, as regulations would dictate, the carcasses of 16,000 dead pigs were tossed in the river. They would then be carried very noticeably to Shanghai and through the city’s public waterways.[14] |

|

|

Do not be misled by the impression that the Chinese public has been docile and accepting of the deteriorating situation. The increasing frequency and severity of these issues has galvanized responses by the Chinese public, with statistics as far back as 1993 showing 63% of Chinese citizens thought that the “environmental problem in China had already interfered with [their] quality of life.”[15] Chai Jing explained that “as wages increased and transparency increased, people’s expectations on the environment rose as well.”[16] Some citizens in the 1990’s tried to emulate Western and post-Soviet methods of activism through the creation of environmental NGOs (ENGOs) in response to the situation.[17] This ENGO activism has not been the leading way for Chinese citizens to voice their irritation, though. The public has increasingly expressed their dissatisfaction through organized petitions, protests, and even riots, all of which have been increasing in size and frequency across China for years.[18] While specifics are not known about recent rises, State Environmental Protection Agency director Zhou Shengxian, himself a CCP official, confirmed that “collective incidents” linked to the environment had been rising as of 2008, and cited pollution as “a major source of social instability.”[19] Elizabeth Economy confirmed that by 2013, environmental outrage has become the leading cause of social unrest in China.[20]

|

|

|

This is the crux of the threat posed to the CCP because of their environmental mismanagement: civil unrest and social upheaval. As growing signs of discontent arise, the “violent collective protests linked to environmental problems have left China’s leaders increasingly worried, as they recognize that is a major factor in social instability.”[21] Two key factors worry them about this: first, that environmental protests are almost always viewed as legitimate actions by a public with legitimate grievances, and second that these environmental movements could seed larger, organized opposition to the Party’s control on power. “Historical traditions of legitimation of environmental revolts persist strongly in… Chinese culture and lend a strong underlying legitimacy to environmental-related social movements in China today. This historical aspect explains… why the government remains wary of these movements.”[22] Considering the historical precedents from the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming who were overthrown in large part because of environmental catastrophes, the Party is especially worried about the popular outrage that can come from the environment.

|

American University of Paris sinologist Susan Perry noted that one of the biggest fears of the Party is a large-scale environmental catastrophe caused by mismanagement that they cannot adequately respond to – for instance, an event like a worldwide pandemic caused by poor environmental regulations and exacerbated by Party mismanagement.[23] The second major concern the Party has with environmentalism is the potential rise of a new, national opposition group that could challenge the Party’s grip on power. The Party is also aware that in other, similar contexts national grassroots environmental campaigns have morphed into grassroots democratic movements,[24] like in the latter days of the Soviet Union. The worst-case scenario for the Party is the rise of a popular, national environmental movement sparked by the government’s mismanagement of the environment that sparks a challenge to the political, social and economic hegemony of China.

he CCP has been aware of the problem of the environment for some time, and they have made efforts to mitigate the problem. Laws against direct pollution have existed since the 1950’s, and even before Deng Xiaoping’s policies of openness and reform, over twenty laws protecting the environment and China’s resources were passed by the People’s Congress.[25] In 1979, the most influential environmental legislation, the Environmental Protection Law,[26] was promulgated and the national State Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) was organized. Jing notes that “During that intervening decade, the central government put unprecedented effort into environmental protection,” adding more environmental laws, stiffening penalties for violators and approving additional green technology to deal with pollution.[27] In the same breath, the CCP also brought China into a series of environmental treaties as they sought to become a member of the wider international community, and they considered environmental agreements to be a “softer field of international relations” that they could more easily accommodate.[28] In addition, all Chinese provinces have their own EPB or Environmental Protection Bureau, a local government organization responsible for overseeing environmental protections. By the mid-1990’s the Party had also permitted the presence of international ENGOs, and more astonishingly, several Chinese ENGOs. While ENGOs in autocratic states and in the latter days of the Soviet Union served as the basis for grassroots democratic opposition, there is no indication that will happen in China.[29] Zeng and Eastin write that while the CCP allows ENGOs to operate, it has only done so after being certain it will pose no threat; the activism of these ENGOs is limited, and critiques of the government can be the death of an organization. Annual requirements to renew operating permits, close observation of activities, and a typical dependency of government funding has mitigated the ability of any organization to grow too large or pose any feasible threat to the regime.[30]

Efforts further intensified in 2008, as SEPA became a ministry level branch of the government, and was reformed into the Ministry of the Environment, further centralizing Beijing’s environmental efforts and policies.[31] The Party has also developed systems for reporting and complaining about pollution to provide another outlet for the public’s frustration other than public demonstrations and unrest. The Ministry of the Environment has hotlines for reporting pollution that average citizens witness,[32] and permits writing complaint letters to the local state Environmental Protection Bureaus (EPBs). In 2010, over 700,000 complaints were registered.[33] The regime has also been investing in green technologies – in 2019, China was responsible for manufacturing a third of all wind turbines globally, and 70% of all solar panels.[34] In addition, the CCP has also signed on to the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement to lower their global emissions, and September of 2020 went even further. In a speech to the United Nations General Assembly, Xi Jinping surprised analysts by pronouncing that “We aim to have emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.”[35] There is undoubtedly some geopolitical motivation behind the announcement, an attempt to take a leadership role in climate change and green technologies in the wake of an apparent American abdication of leadership; but, the fact remains that such a public statement indicated that both Xi and the Party have serious intent to follow through on this goal.

Panorama of the controversial Three Gorges Dam. Besides the destruction to plant, animal and human habitat that is now under water, the criticism is fueled by the fear that the entire geological structure of the area could be fragilized by the weight of all the water poured into the valleys region. Photo (CC BY-SA 3.0) by Leonard G.

|

"If all of these measures exist, and the central government is so intent on following them, then why is China still one of the largest polluting nations on the earth?" |

f all of these measures exist, and the central government is so intent on following them, then why is China still one of the largest polluting nations on the earth?

Simply because the laws and regulations that were just enumerated are not widely enforced - “The key issue in China is enforcement of regulations already on the book – China would be greener and cleaner if existing regulations were enforced” deplores Susan Perry.[37] The problem, it is agreed, stems largely from who enforces the environmental laws –autonomous, local governments, specifically by local Environmental Protection Bureaus.[38] Elizabeth Economy explains that China’s system of “decentralized authoritarianism” is to blame for this, saying that the delegation of enforcement is the key issue.[39] It is not the central Party or the Ministry of Energy who is supposed to be enforcing environment regulations; it is the county EPB offices that are almost always understaffed, overworked, and logistically unable to enforce the regulations. Chai Jing demonstrates this in her documentary by interviewing EPB staff from across the country, who tell her stories about being routinely ignored as factories are literally built, in defiance of their orders, and who are unable to penalize polluting factories Chai Jing’s crew literally recorded polluting.[40] The issue with local enforcement that causes EPB impotence is that structurally, EPB offices report to local, county leadership. The reason that so many EPBs are underfunded is because their funding is supplied by county authorities,[41] leading situations of local protectionism. Even when local officials do allow EPBs to operate, collecting fines and penalizing polluters becomes not only a cost of business for the offenders, but just turns into an additional tax for local government.[42] |

|

Local officials are so reluctant to enforce environmental laws because of the costs. The primary goal of the Party, the key source of the legitimacy over the last half a century has been the economic growth that they have overseen. The key objective for most Party officials is to continue promoting economic growth and self-sufficiency. Additionally, the Chinese Communist Party is still nominally a party of the workers - they must provide jobs for people, making maximizing employment a key secondary goal to promote economic growth.[43] One factory owner even mocked Chai Jing, saying his polluting factory would likely never be shut down because it provided both jobs and economic stimulation to the community.[44] Thus, local leadership if given two opposing directives from the central Party, that they must both maximize economic growth and enforce the environmental laws and regulations that will slow that very growth. “Unfortunately, these officials often attach greater importance to economic development” under rationales deriving from the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis that tries to justify Party inaction.[45] The CCP’s position of economic growth and self-sufficiency over anything else is probably best summed up by a quote from an anonymous country Party leader who told Chai Jing “Everyone says ‘EPB, EPB’ to me. Let me ask you, who would dare slow down China’s economic development?”[46]

|

|

Where does this leave the environment’s potential to foment unrest against the regime? Thus far, the regime seems willing to accept the trade-offs between economic growth and public discontent from degradation. The Party has monitored and eliminated any key organizations that can pose a threat; ENGOs are largely subservient, and no key organization exists that could defy the Party and unite an opposition. While in-person protests and riots still appear to be rising, more and more of the news of environmental unrest has been taking place online as more of the country meets on social media.[47] Through online mediums, the growing and increasingly aware middle class has been able to make some changes – in 2010, ‘netizens’ of the Jilin province took to the internet to spread news and anger over the pollution of a major water source, contradicting the cover story of the government and forcing them to acknowledge the incident. In 2016, pressure from Chinese netizens even forced the Beijing EPB to revamp their air pollution measurement system.[48] And while the Party does closely monitor all internet traffic, especially this potentially seditious kind, they have not outright banned it – rather, the Party has adapted to use online posts and protests as indicators and alert systems to warn of upheaval.[49] As the 2016 incident demonstrated, when discontent grows to a pitch, local governments often just relent and accede to protest demands. In these instances, it should also be noted that it is not the central Party, the key leadership such as Xi Jinping, who takes the publicity fall; usually, anger and frustration targets the local leaders who refuse to regulate and enforce environmental laws.[50]

|

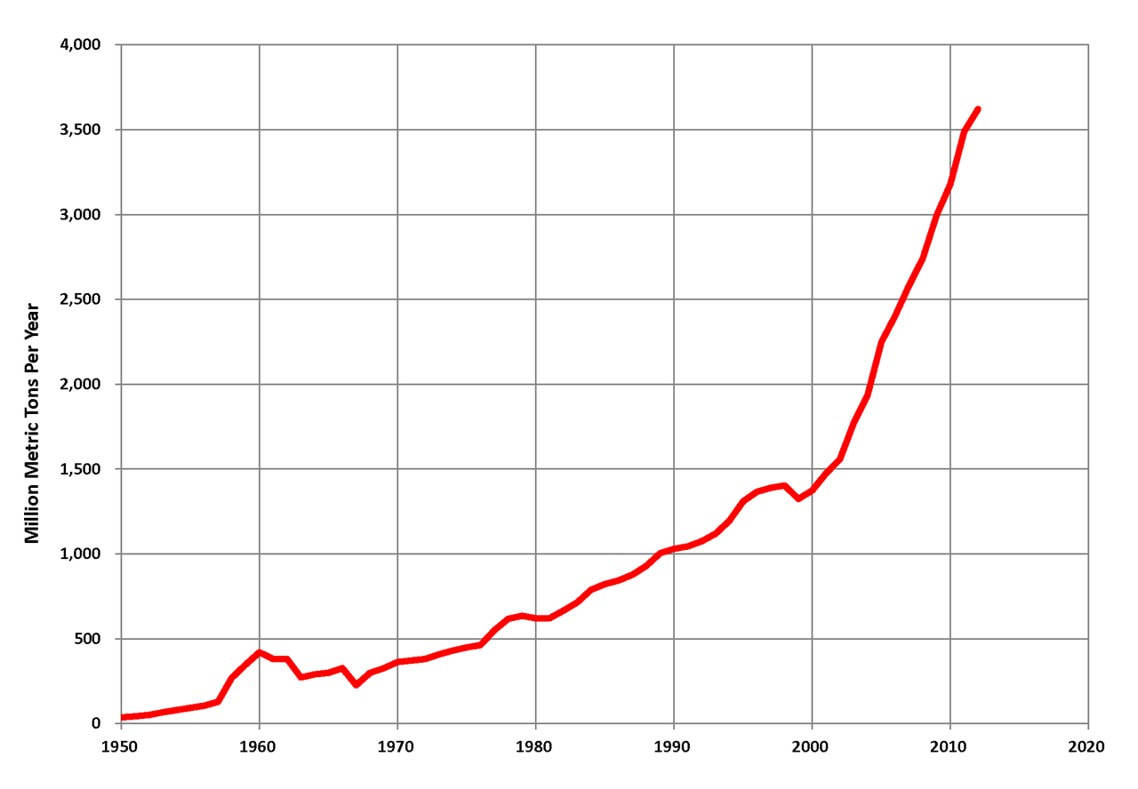

Coal production in China, 1950-2012 (Chart by Plazak)

Chinese authorities, but also many simple citizens of China will ask whether it is legitimate to blame a country for pulling out of poverty through industrial production... as did industrialized countries of the Northern hemispher only a few generations ago.

|

he current environmental movement in China does not seem like it is organized nor potent enough to spark a democratic alternative to the CCP as other environmental movements have done. While nominally pursuing environmental regulations and protections, the authoritarian structure and priorities of the CCP have demonstrated that for the time being, they are willing to continue polluting for the economic advantages it can provide. There was hope that with the lockdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the regime would use the opportunity to push further green technologies and make an effort to truly protect the environment. However, the opposite has been true, as pollution has surpassed the measurements taken in the months before the pandemic began, as the regime scrambles to make up the money lost by the lockdowns.[51] The unrest caused by environmental problems has not dissipated and it seems unlikely it will soon, and the public has demonstrated a strong willingness to apply serious pressure to the Party. For right now though, the regime appears confident that it can accommodate or eliminate any threats that the protests could pose. In the long run, this myopic view of development will likely pose a larger threat than the regime can cope with, but for now it seems managed. As the single largest producer of greenhouse gases, contributing more CO2 to the environment than the US, EU and India combined,[52] China will not just be a leader on climate issues; China will decide the future of the climate. Prioritizing development at all costs may not lead to an environmental revolt or democratic movement, but the CCP’s poor treatment of the environment will affect the Chinese public and the global community in the decades to come.

Notes

[1] “Biodiversity and the Economic Response to COVID-19: Ensuring a Green and Resilient Recovery,” (OECD, September 28, 2020): 2, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=136_136726-x5msnju6xg&title=Biodiversity-and-the-economic-response-to-COVID-19-Ensuring-a-green-and-resilient-recovery.

[2] Elizabeth Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” Report, Council on Foreign Relations, (2013): 4, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00302.

[3] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 479.

[4] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 480.

[5] Li Ma, François G. Schmitt, and N. Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts in China,” China Perspectives, no. 2 (2008): 98, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24053227.

[6] Susan Perry, interview with author, November 25, 2020.

[7] Gerald Chan, Pak K. Lee, and Lai-Ha Chan, "China's Environmental Governance: The Domestic - International Nexus," Third World Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2008): 302, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20455041.

[8] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 492.

[9] Under the Dome: Air Pollution in China, directed by Chai Jing. (2015; Self-Funded), YouTube video, 23:10. www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5bHb3ljjbc.

[10] Jing, Under the Dome, 7:30.

[11] Jing, Under the Dome, 20:47.

[12] Elizabeth Economy, "Environmental Governance in China: State Control to Crisis Management," Daedalus 143, no. 2 (2014): 186, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43297326.

[13] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 97.

[14] Economy, “Environmental Governance in China,” 184.

[15] Bao Maohong, "Environmental NGOs in Transforming China,” Nature and Culture 4, no. 1 (2009): 3, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43304125.

[16] Jing, Under the Dome, 20:04.

[17] Maohong, “Environmental NGOs,” 4.

[18] Jerry McBeath, and Bo Wang, "China's Environmental Diplomacy." American Journal of Chinese Studies 15, no. 1 (2008): 9, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44288862.

[19] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 97-98.

[20] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 4.

[21] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 98.

[22] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 98.

[23] Susan Perry, interview by author, November 25, 2020.

[24] McBeath and Wang, “China’s Environmental Diplomacy,” 9.

[25] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 486.

[26] Chan, Lee, and Chan, “China’s Environmental Governance," 296.

[27] Jun Jing, “Environmental Protests in Rural China,” Essay in Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance, (2010): 198, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.aup.fr/lib/aup/reader.action?docID=496311&ppg=216.

[28] McBeath and Wang, “China’s Environmental Diplomacy,” 1.

[29] Maohong, “Environmental NGOs,” 4.

[30] Ka Zeng, and Joshua Eastin, "Environmental Pollution and Regulation in China," Greening China: The Benefits of Trade and Foreign Direct Investment, (2011): 48-49, doi:10.2307/j.ctvc5pf20.6.

[31] Economy, “Environmental Governance in China, 189.

[32] Chan, Lee, and Chan, “China’s Environmental Governance,” 304.

[33] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 2.

[34] Sarah Ladislaw and Nikos Tsafos, “Beijing Is Winning the Clean Energy Race,” Foreign Policy. October 2, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/02/china-clean-energy-technology-winning-sell/.

[35]Adam Tooze, “Did Xi Just Save the World?,” Foreign Policy, September 25, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/25/xi-china-climate-change-saved-the-world%E2%80%A8/.

[36] Jing, Under the Dome, 38:55.

[37] Susan Perry, interview by author, November 25, 2020.

[38] Zeng and Eastin, “Environmental Pollution,” 45.

[39] Economy, “Environmental Governance in China,” 188.

[40] Jing, Under the Dome, 30:00.

[41] Zeng and Eastin, “Environmental Pollution,” 47.

[42] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 99.

[43] Richard Smith, “The Chinese Communist Party Is an Environmental Catastrophe,” Foreign Policy, July 27, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/27/chinese-communist-party-environment-co2/.

[44] Jing, Under the Dome, 31:37.

[45] Zeng and Eastin, “Environmental Pollution,” 48.

[46] Jing, Under the Dome, 1:05:00.

[47] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 3.

[48] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 4.

[49] Susan Perry, interview by author, November 25, 2020.

[50] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 5.

[51] Smith, “The Chinese Communist Party.”

[52] Tooze, “Did Xi Just Save the World?”

[1] “Biodiversity and the Economic Response to COVID-19: Ensuring a Green and Resilient Recovery,” (OECD, September 28, 2020): 2, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=136_136726-x5msnju6xg&title=Biodiversity-and-the-economic-response-to-COVID-19-Ensuring-a-green-and-resilient-recovery.

[2] Elizabeth Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” Report, Council on Foreign Relations, (2013): 4, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00302.

[3] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 479.

[4] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 480.

[5] Li Ma, François G. Schmitt, and N. Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts in China,” China Perspectives, no. 2 (2008): 98, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24053227.

[6] Susan Perry, interview with author, November 25, 2020.

[7] Gerald Chan, Pak K. Lee, and Lai-Ha Chan, "China's Environmental Governance: The Domestic - International Nexus," Third World Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2008): 302, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20455041.

[8] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 492.

[9] Under the Dome: Air Pollution in China, directed by Chai Jing. (2015; Self-Funded), YouTube video, 23:10. www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5bHb3ljjbc.

[10] Jing, Under the Dome, 7:30.

[11] Jing, Under the Dome, 20:47.

[12] Elizabeth Economy, "Environmental Governance in China: State Control to Crisis Management," Daedalus 143, no. 2 (2014): 186, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43297326.

[13] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 97.

[14] Economy, “Environmental Governance in China,” 184.

[15] Bao Maohong, "Environmental NGOs in Transforming China,” Nature and Culture 4, no. 1 (2009): 3, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43304125.

[16] Jing, Under the Dome, 20:04.

[17] Maohong, “Environmental NGOs,” 4.

[18] Jerry McBeath, and Bo Wang, "China's Environmental Diplomacy." American Journal of Chinese Studies 15, no. 1 (2008): 9, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44288862.

[19] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 97-98.

[20] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 4.

[21] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 98.

[22] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 98.

[23] Susan Perry, interview by author, November 25, 2020.

[24] McBeath and Wang, “China’s Environmental Diplomacy,” 9.

[25] Maohong, “Environmental History,” 486.

[26] Chan, Lee, and Chan, “China’s Environmental Governance," 296.

[27] Jun Jing, “Environmental Protests in Rural China,” Essay in Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance, (2010): 198, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.aup.fr/lib/aup/reader.action?docID=496311&ppg=216.

[28] McBeath and Wang, “China’s Environmental Diplomacy,” 1.

[29] Maohong, “Environmental NGOs,” 4.

[30] Ka Zeng, and Joshua Eastin, "Environmental Pollution and Regulation in China," Greening China: The Benefits of Trade and Foreign Direct Investment, (2011): 48-49, doi:10.2307/j.ctvc5pf20.6.

[31] Economy, “Environmental Governance in China, 189.

[32] Chan, Lee, and Chan, “China’s Environmental Governance,” 304.

[33] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 2.

[34] Sarah Ladislaw and Nikos Tsafos, “Beijing Is Winning the Clean Energy Race,” Foreign Policy. October 2, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/02/china-clean-energy-technology-winning-sell/.

[35]Adam Tooze, “Did Xi Just Save the World?,” Foreign Policy, September 25, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/25/xi-china-climate-change-saved-the-world%E2%80%A8/.

[36] Jing, Under the Dome, 38:55.

[37] Susan Perry, interview by author, November 25, 2020.

[38] Zeng and Eastin, “Environmental Pollution,” 45.

[39] Economy, “Environmental Governance in China,” 188.

[40] Jing, Under the Dome, 30:00.

[41] Zeng and Eastin, “Environmental Pollution,” 47.

[42] Ma, Schmitt, and Jayaram, “Development and Environmental Conflicts,” 99.

[43] Richard Smith, “The Chinese Communist Party Is an Environmental Catastrophe,” Foreign Policy, July 27, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/27/chinese-communist-party-environment-co2/.

[44] Jing, Under the Dome, 31:37.

[45] Zeng and Eastin, “Environmental Pollution,” 48.

[46] Jing, Under the Dome, 1:05:00.

[47] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 3.

[48] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 4.

[49] Susan Perry, interview by author, November 25, 2020.

[50] Economy, “China’s Environmental Governance Crisis,” 5.

[51] Smith, “The Chinese Communist Party.”

[52] Tooze, “Did Xi Just Save the World?”

Bibliography

“Biodiversity and the Economic Response to COVID-19: Ensuring a Green and Resilient Recovery,” OECD Report, September 28, 2020. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=136_136726-x5msnju6xg&title=Biodiversity-and-the-economic-response-to-COVID-19-Ensuring-a-green-and-resilient-recovery.

Chan, Gerald, Pak K. Lee, and Lai-Ha Chan. "China's Environmental Governance: The Domestic: International Nexus." Third World Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2008): 291-314. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20455041.

Economy, Elizabeth. "Environmental Governance in China: State Control to Crisis

Management." Daedalus 143, no. 2 (2014): 184-97. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43297326.

Economy, Elizabeth. Report. Council on Foreign Relations, 2013. Accessed December 1, 2020.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00302.

Jing, Chai, director. Under the Dome: Air Pollution in China. Youtube.com, Self-Funded, 2015,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5bHb3ljjbc.

Jing, Jun. “Environmental Protests in Rural China.” Essay. In Chinese Society: Change, Conflict

and Resistance, 197–214. London: Taylor & Francis Group, (2010), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.aup.fr/lib/aup/reader.action?docID=496311.

Ladislaw, Sarah, and Nikos Tsafos. “Beijing Is Winning the Clean Energy Race.” Foreign Policy.

Foreign Policy, October 2, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/02/china-clean-energy-technology-winning-sell/.

MA, LI, FRANÇOIS G. SCHMITT, and N. Jayaram. "Development and Environmental Conflicts in

China." China Perspectives, no. 2 (74) (2008): 94-102. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24053227.

MAOHONG, BAO. "Environmental History in China." Environment and History 10, no. 4 (2004):

475-99. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20723506.

Maohong, Bao. "Environmental NGOs in Transforming China." Nature and Culture 4, no. 1

(2009): 1-16. Accessed December 21, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43304125.

McBeath, Jerry, and Bo Wang. "China's Environmental Diplomacy." American Journal of Chinese

Studies 15, no. 1 (2008): 1-16. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44288862.

Smith, Richard. “The Chinese Communist Party Is an Environmental Catastrophe.” Foreign

Policy, July 27, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/27/chinese-communist-party-environment-co2/.

Tooze, Adam. “Did Xi Just Save the World ?” Foreign Policy, September 25, 2020.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/25/xi-china-climate-change-saved-the-world%E2%80%A8/.

ZENG, KA, and JOSHUA EASTIN. "Environmental Pollution and Regulation in China." In Greening

China: The Benefits of Trade and Foreign Direct Investment, 37-62. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011. Accessed December 21, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc5pf20.6.

“Biodiversity and the Economic Response to COVID-19: Ensuring a Green and Resilient Recovery,” OECD Report, September 28, 2020. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=136_136726-x5msnju6xg&title=Biodiversity-and-the-economic-response-to-COVID-19-Ensuring-a-green-and-resilient-recovery.

Chan, Gerald, Pak K. Lee, and Lai-Ha Chan. "China's Environmental Governance: The Domestic: International Nexus." Third World Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2008): 291-314. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20455041.

Economy, Elizabeth. "Environmental Governance in China: State Control to Crisis

Management." Daedalus 143, no. 2 (2014): 184-97. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43297326.

Economy, Elizabeth. Report. Council on Foreign Relations, 2013. Accessed December 1, 2020.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00302.

Jing, Chai, director. Under the Dome: Air Pollution in China. Youtube.com, Self-Funded, 2015,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5bHb3ljjbc.

Jing, Jun. “Environmental Protests in Rural China.” Essay. In Chinese Society: Change, Conflict

and Resistance, 197–214. London: Taylor & Francis Group, (2010), https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.aup.fr/lib/aup/reader.action?docID=496311.

Ladislaw, Sarah, and Nikos Tsafos. “Beijing Is Winning the Clean Energy Race.” Foreign Policy.

Foreign Policy, October 2, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/02/china-clean-energy-technology-winning-sell/.

MA, LI, FRANÇOIS G. SCHMITT, and N. Jayaram. "Development and Environmental Conflicts in

China." China Perspectives, no. 2 (74) (2008): 94-102. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24053227.

MAOHONG, BAO. "Environmental History in China." Environment and History 10, no. 4 (2004):

475-99. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20723506.

Maohong, Bao. "Environmental NGOs in Transforming China." Nature and Culture 4, no. 1

(2009): 1-16. Accessed December 21, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43304125.

McBeath, Jerry, and Bo Wang. "China's Environmental Diplomacy." American Journal of Chinese

Studies 15, no. 1 (2008): 1-16. Accessed December 1, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44288862.

Smith, Richard. “The Chinese Communist Party Is an Environmental Catastrophe.” Foreign

Policy, July 27, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/27/chinese-communist-party-environment-co2/.

Tooze, Adam. “Did Xi Just Save the World ?” Foreign Policy, September 25, 2020.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/25/xi-china-climate-change-saved-the-world%E2%80%A8/.

ZENG, KA, and JOSHUA EASTIN. "Environmental Pollution and Regulation in China." In Greening

China: The Benefits of Trade and Foreign Direct Investment, 37-62. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011. Accessed December 21, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc5pf20.6.