Nature & Cultures, the American University of Paris geographic magazine for global explorers - No. 7

“So where are you from?”

“New York”.

“Err… I mean where are your parents from?”

“Paris”.

“Errr… I mean well, errr… Your name doesn’t sound very French…”

This is one of the most frequent conversations I get involved in when meeting people for the first time. Tired of providing necessarily long and complicated answers, over the years I have come up with the following retort.

“When I will become a world celebrity, the Russians will claim that I am the great Russian academic and author Oleg (pronounced All-YEgg) Kobtsev. Ukrainian nationalists will claim me as their own Oleh (Ole-EH) Kobets. But if I become a world renown criminal, both sides will refer to me as “an American mongrel of obscure origins”. Instead of the formula “obscure origins”, the use of some anti-Semitic rhetoric may also to be expected (anti-Semitism is still one of the ugly still shared on both sides of the Ukrainian-Russian divide).

There was a time when I found my wisecrack funny and clever. But not since a war started tearing apart the two countries where all four of my grandparents had deep historic roots. Only one of them was born outside of Ukraine (Warsaw was his birthplace). Also, after many years, I started working again as a volunteer educator in a youth organization where dozens of Russian, Ukrainian and Moldavian children and adolescents – most of them living abroad, often in a mixed family with one French, Belgian, Italian, or even an African parent – camp out together, play games, sing in folk or church choirs, go to dances, enjoy hiking, swimming, ball games and many other activities, and learn about their history and culture, asking me difficult questions about their country of origin. But the real challenge is at home where I am now helping to raise a boy and a girl, two orphans from Ukraine. I have to think more seriously about what I am going to answer about my own Ukrainian, but also my Russian, and Polish, and Baltic, and Tatar family history – all typical components of the populations of both Ukraine and Russia. It is especially difficult to come up with answers about a war that might one day force the kids entrusted to me, in camp and at home, to be thrown, as adults, into enemy factions.

“New York”.

“Err… I mean where are your parents from?”

“Paris”.

“Errr… I mean well, errr… Your name doesn’t sound very French…”

This is one of the most frequent conversations I get involved in when meeting people for the first time. Tired of providing necessarily long and complicated answers, over the years I have come up with the following retort.

“When I will become a world celebrity, the Russians will claim that I am the great Russian academic and author Oleg (pronounced All-YEgg) Kobtsev. Ukrainian nationalists will claim me as their own Oleh (Ole-EH) Kobets. But if I become a world renown criminal, both sides will refer to me as “an American mongrel of obscure origins”. Instead of the formula “obscure origins”, the use of some anti-Semitic rhetoric may also to be expected (anti-Semitism is still one of the ugly still shared on both sides of the Ukrainian-Russian divide).

There was a time when I found my wisecrack funny and clever. But not since a war started tearing apart the two countries where all four of my grandparents had deep historic roots. Only one of them was born outside of Ukraine (Warsaw was his birthplace). Also, after many years, I started working again as a volunteer educator in a youth organization where dozens of Russian, Ukrainian and Moldavian children and adolescents – most of them living abroad, often in a mixed family with one French, Belgian, Italian, or even an African parent – camp out together, play games, sing in folk or church choirs, go to dances, enjoy hiking, swimming, ball games and many other activities, and learn about their history and culture, asking me difficult questions about their country of origin. But the real challenge is at home where I am now helping to raise a boy and a girl, two orphans from Ukraine. I have to think more seriously about what I am going to answer about my own Ukrainian, but also my Russian, and Polish, and Baltic, and Tatar family history – all typical components of the populations of both Ukraine and Russia. It is especially difficult to come up with answers about a war that might one day force the kids entrusted to me, in camp and at home, to be thrown, as adults, into enemy factions.

UKRAINE AND RUSSIA: TWO REGIONS OF THE SAME COUNTRY... OR TWO DIFFERENT CIVILIZATIONS?

|

On the 36th day of war in Ukraine, the author of this article, Oleg Kobtzeff is put on the spot and asked by the presenter of political talk show The Debate on French TV channel France 24 (the French equivalent of CNN or BBC World) about his connections to the land being attacked. He explains how Ukrainians speaking Russian as a mother tongue and previously identifying as Russians could feel completely alienated by Putin's Russian Federation attacking mostly Eastern Ukraine --- essentially Russian speaking territories. Kobtzeff, founding publisher and currently editor-in-chief of N&C Nature & Cultures began his teaching career at the American University of Paris in 1993 analyzing the changes in Central and Eastern Europe in the wake of the collapse of the Berlin Wall and of the Soviet Union. (Screenshot) |

The international media is not helping. Kremlin-controlled news outlets represent the present conflict as a clash of civilizations and a defense against a conspiracy by NATO, the EU and neo-Nazi Ukrainians fomenting civil war within an otherwise happy and united Russian-Ukrainian family. Western media often simplify the issue by representing the violence as a war between bad guys—evil expansionist Russians, and good guys—the Ukrainians, as if the two were completely different geopolitical entities like Germany and England in the World Wars or Israelis and Palestinians. But like in Northern Ireland or Bosnia not so long ago, the issues behind the present conflict in Ukraine are far more complex. They are so complex because, as Ukrainian nationalists rightfully claim, strong dissimilarities separate Russia and Ukraine, but at the same time, there are also, as rightfully claimed by most Russians as well as by a significant minority of Ukrainians, similarities and historical ties that are also strong have interwoven the two peoples into the same fabric for eleven centuries. The history and cultures of Ukraine and Russia are mixed like those of Scotland and England, Corsica and France, Belgium’s Flanders and Wallonia, or Quebec and the rest of the Canadian provinces. A far better example of complex relations between neighboring populations would be the North of the Italian peninsula with Milan and Turin opposed to Rome, Naples or Sicily in the South. Arguments that Northern Italy is a country different from Southern Italy could be supported by numerous historic, cultural, linguistic and especially economic arguments. That both these halves of one Italy constitute the same country can be supported by as many counter-arguments, all based on objective historic and cultural research. This is what makes the present conflict between Ukraine and Russia so painful; the borders between the very diverse people that inhabit that part of Eastern Europe are not as clear cut as they appear on maps, in textbooks and official documents. But saying this puts into question a basic principle in international law: if cultural borders are blurry and porous, what guarantees the respect of the sovereignty of a state and its right to control the destiny of the territory inside its own borders which have been recognized by the international community … including Russia itself, in 1991, when it recognized Ukraine and Belarus as separate independent and sovereign states?

Saint Volodimir, founder of Christian Ukraine or Saint Vladimir, founder of Holy Russia?

|

Open any encyclopedia, in any language (Ukrainian, French, English, Chinese or even Russian), consult the entry “Ukraine” and read about its history. What will you find? A narrative explaining that the country was assembled between the 9th and 10th century by a Scandinavian or Slavic dynasty of princes (scholars have been arguing about their origins for three centuries) who ruled from Kiev – today’s capital of Ukraine. Princess Olha was the first to be baptized and her grandson Volodimir, in 988, began converting the entire population to Christianity. Under Volodimir’s son Yaroslav, who laid the first legislative system of Ukraine, Kiev thrived as the second greatest metropolis of Christendom and Ukrainian literature was born. Now, in the same encyclopedia, look up Russia’s history. We find a narrative about the country being assembled between the 9th and 10th century by a Scandinavian or Slavic dynasty of princes (scholars have been arguing about their origins for three centuries) who ruled from Kiev. Princess Olga (spelled with a “g” not an “h”) was the first to be baptized and her grandson Vladimir (no letter “o” in that spelling), in 988, began converting the entire population to Christianity. Under Vladimir’s son Yaroslav, who laid the first legislative system of Russia, Kiev (“mother of all Russian cities”) thrived as the second greatest metropolis of Christendom and Russian literature was born. Exactly the same story.

Here is the problem: there once was a country called Rus’. Rus’, in the days of Great Prince Vladimir (or Volodimir if you prefer the Ukrainian version) and his son Yaroslav, had become a vast empire extending from the Baltic Sea and the Arctic ocean to the Black Sea, the Danube and the approaches of the Caspian region. Both the Ukrainians and Russians claim to be the descendants of the original inhabitants of Rus’. Ukrainian nationalists and many Western academics deny Russians’ claim to be inheritors of Rus’. The most famous and popular representation of Saint Vladimir or Volodimir (originally Volodimer) the monument by sculptor Peter Clodt, architect Aleksandr Andrejevitj Thon (with sculpted ornaments by Vasily Demut-Malinovsky) overlooking the Dnipro river where in 988, the monarch performed a mass baptism of the population of Kiev (Kyiv in modern Ukrainian)

|

The late Vladimir Vodoff was once the leading specialists in medieval Slavic history and philology in the francophone world. I was lucky to have been one of his students in the late 1970s. I vividly remember what he told us about the representations of “Rus’” in the Middle Ages. Based on ancient documents, his evidence supports the narrative of Ukrainian nationalists. Vodoff pointed out that, in the days when the princes of Kiev ruled over what later became today’s Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, the name Rus’ in the Old Slavic language spoken by the various tribes of Eastern Europe, designated precisely the south-western part of Kiev’s Empire–-basically today’s Ukraine. “‘I am going to Rus’” is how, explained Vodoff, “someone living in far Northern Novgorod announced that he was travelling further South”. In other words, in the medieval representations of the Eastern Slavs, Rus’ meant the territory that is now Ukraine.

Vodoff also mentioned how his family name was really “Voda” but was transformed by the influence of Russian cultural domination, as numerous Ukrainian names, once Russia ruled over what it called “Small Russia”. In Ukraine, a majority of family names are simply names of objects or animals – Voda (Water), Mohila (grave), Skovoroda (pan), Repa (beet), etc. Under Russian rule, my professor’s ancestral name, Voda, was transformed into Vodov (water’s). Repa became Repin (beet’s–-the name of a famous late 19th-early 20th century painter). The grandfather of one renowned writer was named Chekh which means “The Czech”. It is under the russified version of that name that Anton Chekhov became famous. My own family name came from Kobets which means red footed hawk and became Kobtsev (red footed hawk’s). Western (especially under German and Dutch influence) transliterated the “ev” or “ov” ending into “eff” or “off”.

Vodoff also mentioned how his family name was really “Voda” but was transformed by the influence of Russian cultural domination, as numerous Ukrainian names, once Russia ruled over what it called “Small Russia”. In Ukraine, a majority of family names are simply names of objects or animals – Voda (Water), Mohila (grave), Skovoroda (pan), Repa (beet), etc. Under Russian rule, my professor’s ancestral name, Voda, was transformed into Vodov (water’s). Repa became Repin (beet’s–-the name of a famous late 19th-early 20th century painter). The grandfather of one renowned writer was named Chekh which means “The Czech”. It is under the russified version of that name that Anton Chekhov became famous. My own family name came from Kobets which means red footed hawk and became Kobtsev (red footed hawk’s). Western (especially under German and Dutch influence) transliterated the “ev” or “ov” ending into “eff” or “off”.

Beyond Odessa, the coastal region now often referred to by Russians as “New Russia” –- a term created in the days of Catherine the Great when she conquered it over the Ottoman empire and its vassal Crimean Khan –- a very flat and dusty succession of prairies lies between the deltas of the Dnepr and the Danube." Large populations of pelicans inhabit the deltas of the Danube and (on this photo) the Dnepr. (Photo by Goliath, Creative Commons CC BY 1.0)

|

Many other aspects of folklore or daily life allow to easily distinguish Ukrainians from their neighbors in the far North East of Europe, such as adobe houses with thatched roofs vs. log cabins, long mustaches and shaved heads (sometimes with a tuft of hair on top of the skull) vs. long hair and beards. The bandura, a round shaped sort of mandolin or bouzouki is the national Ukrainian instrument while the balalaikas, a triangular shaped string instrument became the national instrument of Russia in the nineteenth century. But there exist far less superficial examples. The natural environment, a long period of living apart between the 14th and 17th centuries, and the most important cultural features of Ukraine and Russia have created much more profound differences.

The natural environment: North vs. South, East vs. West

|

An important Ukrainian region drastically, different from a typical Russian landscape, is in the Ukrainian West: the Carpathian Mountains. Above: Mt. Hoverla highest point in Ukraine in Carpathian National Nature Park, Ivano-Frankivsk province (below). Photos by Robert-Erik - Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

|

A first-time observer who has spent only a few days in both countries can observe the most obvious difference between Ukraine and Russia: nature.

An important Ukrainian region drastically, different from a typical Russian landscape, is in the Ukrainian West: the Carpathian Mountains. With their high altitude and steepness, they are more like the Tyrol or Switzerland than the great plains of the Volga Basin or the zone of flat marshes, lakes and dense pine, aspen and birch forests of Karelia so typical of anyone’s representations of Russia, including the Russians themselves. The Carpathians are nothing less than an extension of the Alps of Western Europe. But of all the landscapes of Ukraine, the most strikingly original, compared to anything that can be found in Russia, is Crimea. In the early 1980s, after a Franco-Russian conference on outer-space research, I was accompanying a group of Soviet scientists travelling along the coast of the French Rivieria. One of them, Professor Pokras (a Lithuanian pioneer of internet) was quietly sleeping. His colleagues were marveling at the cliffs dropping into the Mediterranean as we were approaching Monaco and trying to wake him up:

“Look! Can’t you see how this is beautiful?!” Professor Pokras opened an eye, conceded a bored glance through the window of the bus, mumbled “So what? It’s like Crimea…”, closed his eyes again and went back to sleep. At the time, I was shocked by what I thought was ignorant provincialism. But when I first visited the region of Yalta, I suddenly concurred with Professor Pokras (who, incidentally, had been considerably jet lagged and sleep deprived after very intense negotiations with his French counterparts of the Space Industry). The cliffs of Southern Crimea tumbling straight into the waves were twice the height of what I had seen near Toulon, Nice, Genoa, or anywhere in Greece after many road trips or boat trips along the Mediterranean coast. Some French or Italian coastal mountains may be higher in altitude than their Crimean counterparts, but I have never seen any with such as an impressive elevation above the waters, rising straight like a wall and towering over the Black Sea. Maybe the heights on which is perched the village of Eze in Provence or the rock of Gibraltar could compete with some of the cliffs near |

Yalta. The palm trees and subtropical flowers that have been imported could easily make you believe that you are walking in a botanical garden in Grenada.

Interior Crimea is an almost arid land yet temperate enough and fertile enough to be covered with fruit orchards, vast blue fields of lavender flowers or vineyards. Anyone having travelled to Spain, Sicily, Greece, and especially to nearby Turkey will inevitably compare the landscapes seen there with most of the views of the interior Crimean countryside.

Which leaves such a strong impression that Ukraine is a country of the Mediterranean.

Interior Crimea is an almost arid land yet temperate enough and fertile enough to be covered with fruit orchards, vast blue fields of lavender flowers or vineyards. Anyone having travelled to Spain, Sicily, Greece, and especially to nearby Turkey will inevitably compare the landscapes seen there with most of the views of the interior Crimean countryside.

Which leaves such a strong impression that Ukraine is a country of the Mediterranean.

The rugged cliffs of Crimea and the Mediterranean climate could easily evoke Turkey or Greece, but certainly not a Typical Russian landscape.

Above: a wing of the palace of the Tatar Khans in Bakhchisaray. Below: the Inkerman Cave Monastery in the rock formations near Sebastopol.

Above: a wing of the palace of the Tatar Khans in Bakhchisaray. Below: the Inkerman Cave Monastery in the rock formations near Sebastopol.

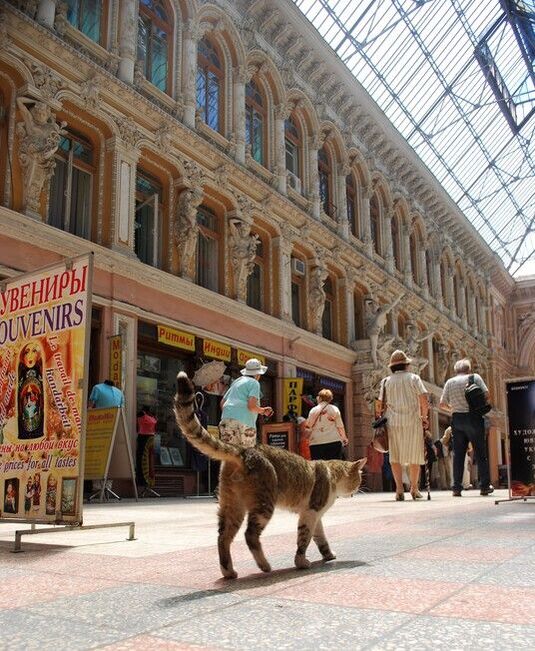

A distinctive Mediterranean atmosphere definitely characterizes the coast of the Black Sea, further North, which gives cities, particularly Odessa, an air of French or Italian Riviera. Like all communities in this maritime area–-conquered from the Ottomans by Catherine the Great–-Odessa, the great 18th century seaport from which Ukrainian wheat was exported throughout Europe until the reign of the last tsar, enjoys a very mild climate which affects the urban landscape. In the historic center, public parks with luxuriant flowers and palm trees border 19th century neo-classic or neo-baroque buildings reminiscent of Monaco or downtown Thessalonica. Further away, the residential areas with their four or five story buildings and outside balconies shaded by the arching acacias aligned for miles along the avenues, evoke the small cities of Provence or some residential districts of Rome. Many say that they have felt this southern European atmosphere as far North as Kiev, and after visiting the Ukrainian capital for the first time, I definitely agreed.

|

The great staircase connecting the seaport straight to a major downtown plaza was made famous by Eisenstein's film "Battleship Potiomkin". The massacre of a crowd of demonstrators by the army was a completely fictitious event.

|

The great staircase connecting the seaport straight to a major downtown plaza was made famous by Eisenstein's film "Battleship Potiomkin". The massacre of a crowd of demonstrators by the army was a completely fictitious event.

|

Beyond Odessa, the coastal region now often referred to by Russians as “New Russia” –- a term created in the days of Catherine the Great when she conquered it over the Ottoman empire and its vassal Crimean Khan –- a very flat and dusty succession of prairies lies between the deltas of the Dnepr and the Danube and the Sea of Azov under the light of a very bright sun. It resembles the coastal area and the plains of North-eastern Italy, near Ravenna or Venice. My father’s mother was born in this kind of landscape, in Mykolaev, on the Bug river. On the border of Ukraine and Moldavia, at the estuary of the Danube, millions of pelicans, sturgeons, wild boars, and multitudes of other species live in one of the greatest wetlands of the Northern Hemisphere. It is the Chesapeake Bay, or maybe parts of the Mississippi river, that it resembles the most and makes this ecosystem so different from anything you can find not only in Russia – the wetlands along the Svir and Neva rivers near Saint Petersburg are too sub-Arctic to bear the comparison – but in all of Europe.

|

As you travel further North, towards the center of Ukraine, the plains rapidly become greener. Rolling hills are very rare and never very high. It is a tame landscape made of vast pastures and fields of cereal crops domesticated by generations of farmers and separated by a few oaks and chestnut trees, and numerous elms, lime trees, alders, common ashes and other deciduous trees. This is the great Western European plain that creates a geographic unity across a vast area that extends from the coasts of Normandy, Belgium and Holland to the Don Basin and includes most of Germany, Hungary, Romania, and Poland.

A much more rugged environment is what many would have expected to recognize as the land in which was born the culture of the Cossacks who ruled the Ukrainian plains from the turn of the 16th and 17th to the early 1920s when they were crushed by the Red Army. But the fierce image of these horsemen contrasts with some of the tranquil landscape around the stanittsy ––their fortified camps. I must confess that I was disappointed when I finally had the chance to discover the ancestral land of my father’s father, the country of the Zaporogian Cossacks, the wildest and most independent of these tribal groups and who were never officially chartered by the tsars like all other Cossacks. I was anticipating a wilderness comparable to the panoramic vistas of Mongolia or Central Asia. I was going to take photos and proudly post that on Facebook for my Native American friends (particularly my old Apache friend and former student Joe Billy who always teased the pale face green horn that I was when we became friends). I was going to show them that my ancestors were as untamed as were the Oglala or the Cheyenne and the land that shaped their culture. Instead, while strolling on the footpaths of Zaporozhie region, I had the impression that I was looking at the countryside just outside of my house in the Vexin, the little region between Paris and Normandy. An unexpectedly tame landscape is the natural environment of the homeland of the Cossacks in the interior of the Zaporozhie region.

|

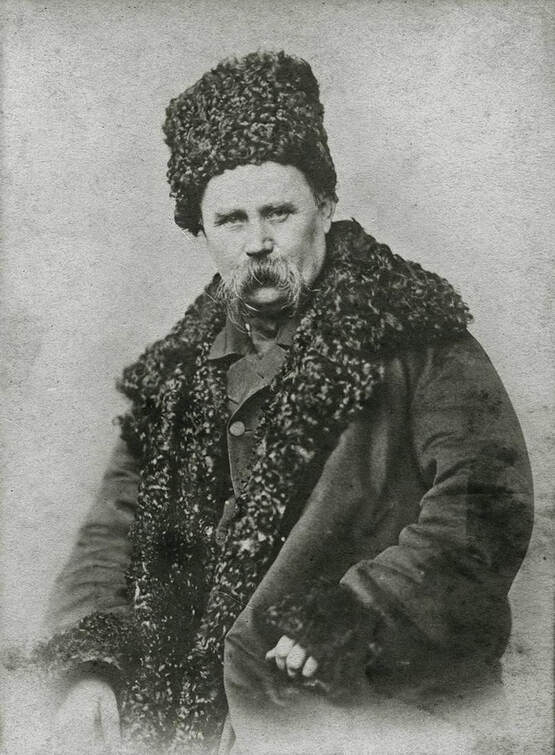

The height of the cliffs above the Dnepr and the vastness of the river are breathtaking as seen from the historic center of Kiev or from the heights of the Shevchenko Historic Park near Kanev. But this offers is no more a view of any wilderness than the cliffs of Dover or of Normandy. Kanev is the town near which Ukraine’s national poet Taras Shevchenko had his home–-a modest khata, a typical thatched-roofed adobe house so different from the Russian log cabins.

Common denominators?

And then, as you travel North, just when you pass Kiev, suddenly, everything changes. A natural border has been crossed. The main feature of the landscape are now forests of tall evergreens. They soar over wider fields and prairies. Everything is on a larger scale like in the great Plains of the American West. This is the wilderness that characterizes Scandinavia, Russia and Belarus. The Oglala and the Cheyenne would have felt at home here when not so long ago, bison used to roam these lands (the last descendants of the European species still live not far from the most northwestern limits of Ukraine, only 120km further North, in the forest of Białoweżia (or Belowezha) separated by the border between Poland and Belarus).

The landscape is beginning to look a lot like Russia.

Other than the contrast between the landscapes of far Western and Southern Ukraine and most of European Russia, not only are there no noticeable differences between the Northern Ukrainian and Russian or Belarussian grasslands, agricultural fields, and forests, but there is no natural border between these countries.

The landscape is beginning to look a lot like Russia.

Other than the contrast between the landscapes of far Western and Southern Ukraine and most of European Russia, not only are there no noticeable differences between the Northern Ukrainian and Russian or Belarussian grasslands, agricultural fields, and forests, but there is no natural border between these countries.

|

The riverport of Kherson' on the Dnepr (photo on top). The width and depth of rivers of Russia and Ukraine allow the largest maritime vessels to connect the North and South of Europe which explains the strategic value of these waterways. Kherson has been affected by heavy bombings (left; photo by Ukrainian Natiional Police), occupation by Russian Federation troops and deliberate destruction of infrastructures when these troops retreated last fall (photo above, right, by Ukrainian National Police).

|

The waterways that connect and shape Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

Public opinions, governments, artists, journalists, or scholars will all agree that it is the great waterways, the Danube, the Bug, the Dniester, the Dnepr, the Don, the Volga, the Oka, the Dvina, the Volkhov, or the Neva—rivers all interconnecting with one another through their tributaries or through canals built between the early 18th and mid-20th centuries and branching out into wide networks of waterways between the Baltic, the Mediterranean, the Caspian and Central Europe—that shaped what became “Russia”, “Ukraine” and “Belarus”. In its earliest historic mentions, the fluvial roads between the Arctic to the Middle East was called “The route from the Varangians to the Greeks”. Like the Silk Road, it was not just one road but an intricate and vast network. Navigable rivers and lakes, many communicating with each other, were often separated by only a very short stretch of land. Travelers would then briefly resort to other means of transportation to connect two waterways by land or to circumvent obstacles such as the infamous rapids on the Dnepr located halfway between its delta and Kiev. This network allowed Scandinavians travelling on their long ships, local Slavs, but also Arab merchants, Greeks, and Romans to connect Asia and Europe. They could circumnavigate all of Europe from the Atlantic, to the English Channel, to the Northern Sea, to the Baltic and the Mediterranean and back into the Atlantic through this Varangian route. The trade posts that emerged on its banks, once unified, became Rus’—arguably the second most prestigious European civilization of the 11th and 12th centuries after Byzantium—the realm claimed today by Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians as the origin of their own state and culture. A realm called Rus’. Rus’ became the crossroads of several civilizations, bringing together the Eastern Slavs and the cultures of the Balkans, of the Baltic, of the Mediterranean and especially of Byzantium that created through missionary activity the most important of the common foundation of the future Eastern and Southeastern Slavic kingdoms and principalities: the Eastern Orthodox Church (see the article in this current issue No. 6 of N&C – Nature & Cultures). The Mediterranean with its Black Sea is therefore part of the foundational representations of their identity by the Ukrainians and the Russians. For the former, their entire South border is the sea. For the latter, ever since they have been separated a first time from Ukraine in the Middle Ages, their right to access those warm waters is an almost obsessive objective that has defined their foreign policy.

Which demonstrates the relevance of studying history. The representations of history are what shapes the identities of millions of people and justify the ideologies of those in power or of those who challenge them.

Which demonstrates the relevance of studying history. The representations of history are what shapes the identities of millions of people and justify the ideologies of those in power or of those who challenge them.

Blurred cultural borders?

Until the 1990s, the Russian representation of the history and cultures of Russia and of Ukraine were those that dominated all narrations worldwide. These narrations imposed the representation of Ukraine as a province of Russia with some regional particularities like Siberia or the Volga basin. Since the Ukrainian independence of 1991, Western narratives switched to a diametrically opposed version which tends to exclude common denominators between Ukraine and Russia described as countries with no more similarities than France and Germany or Japan and China, with Russia sometimes described as an occupying power. But which is the accurate representation? Or can there even be one, since the answers to that question are so numerous and complex? In fact, like the Irish of Ulster or the Belgians, Ukrainians themselves did not fully agree on the same representations of their own country and themselves. The war changed that, as tens of thousands of Russian-speaking Ukrainians rushed to take lessons in the Ukrainian language, and, like myself made great efforts to re-appropriate the characteristically and unique Ukrainian features of their family roots.

The following facts remain indisputable.

By the end of the 9th century, the princes of Kiev (later named Kyiv—pronounce “key-eef” —as the Ukrainian language developed) Oleh (or Oleg, the Northerner who conquered it) Ihor’ (Igor), his wife Ol’ha (Olga) and their son Sviatoslav had gained control of the tribes living in territories themselves dominated by important trading posts such as Izborsk, Polotsk, Rostov, Murom, Smolensk, Iskorosten (now Korosten'), Chernigov (later Cherenihiv in Ukrainian), Novgorod or Ladoga standing on rivers cutting through lands that are now Ukraine , Belarus, and the European part of Russia. The center of these cities, just like Kiev’s, often formed a citadel fortified by a wooden palisade—a kreml’ or kremlin.

The following facts remain indisputable.

By the end of the 9th century, the princes of Kiev (later named Kyiv—pronounce “key-eef” —as the Ukrainian language developed) Oleh (or Oleg, the Northerner who conquered it) Ihor’ (Igor), his wife Ol’ha (Olga) and their son Sviatoslav had gained control of the tribes living in territories themselves dominated by important trading posts such as Izborsk, Polotsk, Rostov, Murom, Smolensk, Iskorosten (now Korosten'), Chernigov (later Cherenihiv in Ukrainian), Novgorod or Ladoga standing on rivers cutting through lands that are now Ukraine , Belarus, and the European part of Russia. The center of these cities, just like Kiev’s, often formed a citadel fortified by a wooden palisade—a kreml’ or kremlin.

The origins of the Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian languages

The dialects of those tribes living in and around those urban centers were at the time diverse. However, except for Asian populations in the East, Finno-Ugric and other Indigenous ethnic groups in the Baltic or sub-Arctic and Polar regions, the ancestors of the Ukrainians, of the Belarussians or of the Russians were linguistically very close.

The written language of Slavonic was created by Byzantine Missionaries sent to Moravia in the 9th century. This artificial language also referred to as “Church Slavonic” by linguists and philologists is a synthesis of numerous ancient Slavic dialects. It was a sort of “Esperanto” codified by the famous siblings Saints Cyril and Methodius who proselytized among Western and Southern Slavs when the first successors of Charlemagne reigned further West over the remains of his empire. Church Slavonic was based on the language of the expatriate communities of Slavs living in the Byzantine empire—war prisoners, slaves, servants, mercenaries, and merchants from all over Central and Eastern Europe, who developed it over a few generations as they communicated among themselves especially where their population was very dense, like Thessaloniki. It is in the region of that city of Nort-Eastern Greece where the high-ranking aristocrats Cyril and Methodius studied the local trans-Slavic dialect, codified its grammar, and invented for it the Glagolitic alphabet that looked very much like Scandinavian runes. A generation later, their disciples reinvented a much simpler alphabet based on most of the letters used in Greek. It is the alphabet called Cyrillic, in honor of Saint Cyril, an alphabet still in use today (with less ornate, modern letters) by Ukrainians and Russians, but also Bulgarians, Serbs and Macedonians, plus (under Russian colonial influence) Central Asian nations and Indigenous Siberians. It was even used by Romanians until the 18th century. Although Moravians would soon adopt Latin as the exclusive language used in church, their modern Czech descendants retained pride in these roots more than a thousand years later as evidenced by the beautiful "Glagolitic Mass" a Church Slavonic liturgical text put into music by Czech composer and ardent panslavist and russophile Leoš Janáček in 1926. Characteristically, historians of different nationalities—Greeks, Macedonians, and Bulgarians—have been trying, for a long time, to prove that these inventors of the Slavic alphabet had roots in their own country. It is petty nationalism, but it also reveals how the two brothers became a common icon for all Slavic identities. The written language they constructed, when read publicly in church services, was easily understandable by all early medieval Slavic people from the Moravians in the far West, to the tribes living in the far Eastern basin of the Volga, to the Serbs and Croats in the Balkans. Devised by the missionaries for translating all the scriptures and the liturgy for all Slavs, it is still the liturgical language in Orthodox places of worship in all of Russia, all of Belarus, a majority of parishes in Ukraine, and, until very recently, in churches throughout Serbia, Bulgaria, and Macedonia. Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians who have received a good religious education and who frequently attend Church services are either fluent in Church Slavonic (for those who have sung in a choir for years, studied in religious schools or are Church geeks) or are at least familiar with some key words of the language heard during services or read in prayer books. Professional or amateur musicians are also familiar with Church Slavonic because all the lyrics for any classical religious music written by Ukrainian, Belarussian, or Russian composers whether these were anonymous medieval monks or mid-20th century concert hall celebrities like Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninov, was in that ancient language. Marie Stravinsky whose famous great-grandfather Igor had deep roots in Poland, Russia, and, through his wife, in far-Western Ukraine, recently revealed to me how, living in exile on the French Riviera in the 1920s, he attended the services of the Russian cathedral in Nice and composed liturgical music for its choir. The words, of course, were in Church Slavonic.

It is in Old East Slavic a language almost similar to Church Slavonic that "The Sermon on Law and Grace" was written between 1037 and 1050 by the first indigenous cleric to be consecrated a bishop of Kiev (as it was still called at the time), the Metropolitan Archbishop Ilarion. This document is described by almost all Ukrainian textbooks as the first composition of Ukrainian literature. Russian textbooks all claim it as the first in the history of Russian literature. When reading the text in its original language, appearances seem to support the Russian version. Indeed, Ilarion calls the possessions of Kiev's rulers the zemlya rooskaya—the Russian land. Its people are called narod rousskoy (“вера благодатная распростёрлась по всей земле и достигла нашего народа русского / the grace-filled faith spread throughout the earth and reached our Russian people”). Ukrainians who attempt to distance themselves from Russia and Russian culture have been avoiding this problem. In all the written traces and oral traditions, the territories included in the Kievan Empire are called Rus'. For centuries, Rus' has been translated as "Russia" in English and Italian, "Russland" in German, "Russie" in French or "Rusia" in Spanish. In Greek, the Byzantines called Rus' «η χώρα των Ρως» (i khora ton Ros i.e. “land of the Ros”) or simply “Ρωσία” ("Rossiya"), and so do modern Greeks. This Greek name progressively became the name used in the Northern half of what had once been the Empire of Kiev and which fell apart in the mid-1200s after the Mongol invasion. By the 15th Century, the Princes of Moscow, soon to be elevated to the rank of "tsars" (Caesars), were commonly using the name "Rossiya". Rus', however, remained in common use in Ukraine, Russia and Blearus. Russians often use “Rus’” it even today to speak of their country when evoking their past in the same way as Anglo-Saxons speak of “Britannia” instead of the Biritish Isles or the United Kingdom. Sometimes the name Rus' is pronounced with the intention of representing Russia as something venerable and great: "Holy Russia" I n the original tongue is "Sviataya Rus’”, not "Sviataya Rossiya”. When Stalin during World War II all but shelved the internationalism of Marxism and Bolshevism of the 1920s and 1930s, he commissioned the Armenian Gabriel El-Registan and the Russian Sergey Mikhalkov (father of movie directors Nikita Mikhalkov and Andrei Konchalovskiy) to write the lyrics of a new Soviet anthem to replace the 19th Century French Communist "Internationale" that had been sung in Russian. The first the first words are "An unbreakable union of free Republics has been welded forever by the great Rus'”. Not Rossiya. But Rus’ is what Ukrainians claim is their country which they distinguish from Rossiya, a separate entity in their representations.

The written language of Slavonic was created by Byzantine Missionaries sent to Moravia in the 9th century. This artificial language also referred to as “Church Slavonic” by linguists and philologists is a synthesis of numerous ancient Slavic dialects. It was a sort of “Esperanto” codified by the famous siblings Saints Cyril and Methodius who proselytized among Western and Southern Slavs when the first successors of Charlemagne reigned further West over the remains of his empire. Church Slavonic was based on the language of the expatriate communities of Slavs living in the Byzantine empire—war prisoners, slaves, servants, mercenaries, and merchants from all over Central and Eastern Europe, who developed it over a few generations as they communicated among themselves especially where their population was very dense, like Thessaloniki. It is in the region of that city of Nort-Eastern Greece where the high-ranking aristocrats Cyril and Methodius studied the local trans-Slavic dialect, codified its grammar, and invented for it the Glagolitic alphabet that looked very much like Scandinavian runes. A generation later, their disciples reinvented a much simpler alphabet based on most of the letters used in Greek. It is the alphabet called Cyrillic, in honor of Saint Cyril, an alphabet still in use today (with less ornate, modern letters) by Ukrainians and Russians, but also Bulgarians, Serbs and Macedonians, plus (under Russian colonial influence) Central Asian nations and Indigenous Siberians. It was even used by Romanians until the 18th century. Although Moravians would soon adopt Latin as the exclusive language used in church, their modern Czech descendants retained pride in these roots more than a thousand years later as evidenced by the beautiful "Glagolitic Mass" a Church Slavonic liturgical text put into music by Czech composer and ardent panslavist and russophile Leoš Janáček in 1926. Characteristically, historians of different nationalities—Greeks, Macedonians, and Bulgarians—have been trying, for a long time, to prove that these inventors of the Slavic alphabet had roots in their own country. It is petty nationalism, but it also reveals how the two brothers became a common icon for all Slavic identities. The written language they constructed, when read publicly in church services, was easily understandable by all early medieval Slavic people from the Moravians in the far West, to the tribes living in the far Eastern basin of the Volga, to the Serbs and Croats in the Balkans. Devised by the missionaries for translating all the scriptures and the liturgy for all Slavs, it is still the liturgical language in Orthodox places of worship in all of Russia, all of Belarus, a majority of parishes in Ukraine, and, until very recently, in churches throughout Serbia, Bulgaria, and Macedonia. Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians who have received a good religious education and who frequently attend Church services are either fluent in Church Slavonic (for those who have sung in a choir for years, studied in religious schools or are Church geeks) or are at least familiar with some key words of the language heard during services or read in prayer books. Professional or amateur musicians are also familiar with Church Slavonic because all the lyrics for any classical religious music written by Ukrainian, Belarussian, or Russian composers whether these were anonymous medieval monks or mid-20th century concert hall celebrities like Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninov, was in that ancient language. Marie Stravinsky whose famous great-grandfather Igor had deep roots in Poland, Russia, and, through his wife, in far-Western Ukraine, recently revealed to me how, living in exile on the French Riviera in the 1920s, he attended the services of the Russian cathedral in Nice and composed liturgical music for its choir. The words, of course, were in Church Slavonic.

It is in Old East Slavic a language almost similar to Church Slavonic that "The Sermon on Law and Grace" was written between 1037 and 1050 by the first indigenous cleric to be consecrated a bishop of Kiev (as it was still called at the time), the Metropolitan Archbishop Ilarion. This document is described by almost all Ukrainian textbooks as the first composition of Ukrainian literature. Russian textbooks all claim it as the first in the history of Russian literature. When reading the text in its original language, appearances seem to support the Russian version. Indeed, Ilarion calls the possessions of Kiev's rulers the zemlya rooskaya—the Russian land. Its people are called narod rousskoy (“вера благодатная распростёрлась по всей земле и достигла нашего народа русского / the grace-filled faith spread throughout the earth and reached our Russian people”). Ukrainians who attempt to distance themselves from Russia and Russian culture have been avoiding this problem. In all the written traces and oral traditions, the territories included in the Kievan Empire are called Rus'. For centuries, Rus' has been translated as "Russia" in English and Italian, "Russland" in German, "Russie" in French or "Rusia" in Spanish. In Greek, the Byzantines called Rus' «η χώρα των Ρως» (i khora ton Ros i.e. “land of the Ros”) or simply “Ρωσία” ("Rossiya"), and so do modern Greeks. This Greek name progressively became the name used in the Northern half of what had once been the Empire of Kiev and which fell apart in the mid-1200s after the Mongol invasion. By the 15th Century, the Princes of Moscow, soon to be elevated to the rank of "tsars" (Caesars), were commonly using the name "Rossiya". Rus', however, remained in common use in Ukraine, Russia and Blearus. Russians often use “Rus’” it even today to speak of their country when evoking their past in the same way as Anglo-Saxons speak of “Britannia” instead of the Biritish Isles or the United Kingdom. Sometimes the name Rus' is pronounced with the intention of representing Russia as something venerable and great: "Holy Russia" I n the original tongue is "Sviataya Rus’”, not "Sviataya Rossiya”. When Stalin during World War II all but shelved the internationalism of Marxism and Bolshevism of the 1920s and 1930s, he commissioned the Armenian Gabriel El-Registan and the Russian Sergey Mikhalkov (father of movie directors Nikita Mikhalkov and Andrei Konchalovskiy) to write the lyrics of a new Soviet anthem to replace the 19th Century French Communist "Internationale" that had been sung in Russian. The first the first words are "An unbreakable union of free Republics has been welded forever by the great Rus'”. Not Rossiya. But Rus’ is what Ukrainians claim is their country which they distinguish from Rossiya, a separate entity in their representations.

Kievan Rus': A gigantic empire.

|

The empire of Kyiv (called Kiev at the time) and its dependant principalities. Almost all of today's European regions of Russia were subjects of Kiev.

|

Rus’, the empire ruled by Kiev, extended from the Baltic to the Black Sea and the Caspian, included the basins of the rivers Dnepr, Don and Volga, it was represented by Ilarion in his "The Sermon on Law and Grace" as one country inhabited by one people united in one state. Most importantly, the central theme of this foundational monument of Ukrainian and Russian cultural history, was that all the tribes the Dnepr, Don and Volga basins were united by the great prince of Kiev Volodimer from 988 and in the following decades of his reign into one Christian church praying in a language almost similar to their native tongue: “every land and every city and every nation honors and glorifies its teacher that taught it the Orthodox faith. We too, therefore, let us praise to the best of our strength, with our humble praises, him whose deeds were wondrous and great, our teacher and guide the great kagan Volodimer.” The next great monument of Old East Slavic literature, The Tale of Bygone Years was written and compiled at the beginning of the 12th century in the first monastery of Kiev, by one of its monks, Nestor the Chronicler. It begins with the words “These are the narratives of bygone years regarding the origin of the land of Rus’” and also represents the lands ruled by Kiev between the Baltic and the Black Sea as one nation united by the Orthodox Church.

Every land and every city and every nation honors and glorifies its teacher that taught it the Orthodox faith. We too, therefore, let us praise to the best of our strength, with our humble praises, him whose deeds were wondrous and great, our teacher and guide the great kagan Volodimer.” The title “kagan” evidently comes from the Asian tribes that had dominated Kiev and other regions of of Rus’ for generations until the rise to power of princes like Oleh, Ihor’, Sviatoslav and Volodimer (Volodimir in Ukrainian, Vladimir in Russian). "The Sermon on Law and Grace" (sermon by first native bishop of Kyiv, Illariion in the early-mid 11 th century). |

The "Tale of Bygone Years"

The history of Rus’ as represented in Nestors’ Chronicle, The Tale of Bygone Years, begins in the mid 9th century. Many pages are devoted to the unification and christianization of Rus’ and the North-Eastern Slavic woodlands under the Princes of Kiev. This document which conveys most of the foundational myths that forged Ukrainian and Russian identity never denies the numerous divisions between the regions of Rus’. But it never acknowledges any North South conflict or division, with the exception perhaps of several mentions of the particularity of the city of Novgorod (for example its resistance to Christianity). But Novgorod was the northern, almost subarctic extremity of this great empire which was Rus’, and the only conflicts we find between cities (at least after the finalization of some conquests by Kiev) are more about the power struggles of individual princes who were not necessarily attached to a particular region (Oleh and Vladimer were originally from the Far North before they made Kiev their capital) rather than geopolitical interregional wars.

WHERE RUSSIAN AND UKRAINIAN CULTURES BEGIN TO SEPARATE

Kiev remained the real political center of Kievan Rus’, at least until the death of one of its most prestigious and wise Great Princes, Volodimer Monomakh and his son Mstislav the Great (in 1132). Kiev formally continued to be considered the state capital and siege of the Great Prince but it was a constant object of struggle between the princes who oversaw smaller cities and the surrounding regions they governed in the name of the Great Prince of Kiev. These wars between the principalities were severely dividing and ruining Rus’ as a state. In 1169, Kiev was conquered and looted by Andrei Bogolyubsky, prince of the powerful city of Vladimir, located 180 kilometers East of where the small settlement of Moscow had just been founded. In 1203, the prince of Smolensk Rurik Rostislavovich also raided Kiev which by then was on its way to become all but a ghost town. The princes of the North who reigned over the cities of Vladimir and Suzdal’, and who would later move to Moscow, claimed the title of Great Prince of Rus’ but, like Andrei Bogolyubsky, did not bother to reclaim the rapidly declining old capital of Kiev as siege of their throne. Modern Ukrainian representations of Ukraine’s history present this evolution of the relation between Kiev and the other principalities—most of today’s Russia—as the definite break between what was to become Ukraine and Russia.

The primate of Rus’, Archbishop-Metropolitan of Kiev Maxim, moved first to Briansk, then to Vladimir in 1299. From the city of Vladimir, then from Moscow, his successors continued to preside over the Church of all the territory that had been Rus’, still bearing the title of Archbishop-Metropolitan of Kiev. In 1468, they switched their title to “Metropolitan of Moscow and of all the Rus’ (in the plural)”. This expression “of all the Rus’” (often translated as “of all the Russias”) which would soon be used by the first tsars and then by all their successors refers to “Great, Small and White Rus’” a Muscovite representation of what is now Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The name Ukraine and Ukrainians would almost never be used in the Muscovite state. Instead the country was called small Russia (Malorossiya) and its inhabitants “Small Russians” —Malorossiyane or Malorossy.

The primate of Rus’, Archbishop-Metropolitan of Kiev Maxim, moved first to Briansk, then to Vladimir in 1299. From the city of Vladimir, then from Moscow, his successors continued to preside over the Church of all the territory that had been Rus’, still bearing the title of Archbishop-Metropolitan of Kiev. In 1468, they switched their title to “Metropolitan of Moscow and of all the Rus’ (in the plural)”. This expression “of all the Rus’” (often translated as “of all the Russias”) which would soon be used by the first tsars and then by all their successors refers to “Great, Small and White Rus’” a Muscovite representation of what is now Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The name Ukraine and Ukrainians would almost never be used in the Muscovite state. Instead the country was called small Russia (Malorossiya) and its inhabitants “Small Russians” —Malorossiyane or Malorossy.

“Borderland”, “The Frontier”: The origins of modern Ukraine

In 1240, Kiev was plundered and destroyed by the Mongol-Tatars. The Kiev principality continued to exist under the Mongol-Tatar yoke, it continued to be ruled by the descendants of Saint Volodimer/Vladimir/Volodimir, but they were now (like the princes of Moscow and the other Russian cities) vassals of the descendants of Genghis Khan.

Then came another change. It would broaden the separation between what would become the Muscovite state and Ukraine. In the mid 1320s, the Lithuanians won the Battle of the Irpin River, against the army of Kiev. The winner, my maternal grandmother’s ancestor, Grand Duke of Lithuania Gediminas, founder of the great state out of which were born the three Baltic states of modern times and that would become one of the great regional powers of mediaeval Europe took away the Kiev principality from its local dynasty and from Mongol authority, making it a vassal of Lithuania.

Until 1569, Kiev and its region were part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. When that state and the Kingdom of Poland united to form the large and powerful Catholic Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 to 1654 the former principality of Kiev became officially part of the lands of the Crown of Poland.

Then came another change. It would broaden the separation between what would become the Muscovite state and Ukraine. In the mid 1320s, the Lithuanians won the Battle of the Irpin River, against the army of Kiev. The winner, my maternal grandmother’s ancestor, Grand Duke of Lithuania Gediminas, founder of the great state out of which were born the three Baltic states of modern times and that would become one of the great regional powers of mediaeval Europe took away the Kiev principality from its local dynasty and from Mongol authority, making it a vassal of Lithuania.

Until 1569, Kiev and its region were part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. When that state and the Kingdom of Poland united to form the large and powerful Catholic Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 to 1654 the former principality of Kiev became officially part of the lands of the Crown of Poland.

Oukraina (Оукраина) seems to have been first mentioned in 1187, as the name of the territory of the Principality of Pereyaslavl’. The proper name "Ukraine" appears to have officially been used for the first time to designate much of what we know today of that territory during in 1580 in the title of and Act passed by the Sejm (parliament) of the of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: "Order in the Lowlands and Ukraine". At that time, it defined the areas of the Kiev and Bratslav regions. In 1613, on the map of Tomasz Makowski, published in Amsterdam, the area of the right bank of the Dnieper (Dnipro) river was defined as “Wołyń Dolny, which is called Ukraine or Lowlands”. In documents archived between 1634 and 1686, “Ukraine” also included the region ("Voivodship") of Chernihiv (known as Chernigov in Russian). In 1648, Guillaume Levasseur de Beauplan the famous cartographer from Normandy, who travelled extensively, worked and fought in Ukraine published the map Delineatio Generalis Camporum Desertorum vulgo Ukraina..., treating the names "Wild Fields" and "Ukrainie" interchangeably. In the same author’s 1651 Description de l’Ukrainie, describing numerous provinces of the Kingdom of Poland lying between the borders of Moscow and Transylvania, Ukraine is shown as extending between the borders of the Russian Tsardom and Transylvania, minus Red Ruthenia. Samuel Grądzki, the Polish diplomat who authored a history of the uprising of Bogdan Khmelnytsky (with whom he negotiated during the conflict) defined Ukraina as the land located at the edge of the Polish kingdom.

The Cossacks

|

Cossack form the Black Sea coastal regions in typical native dress.

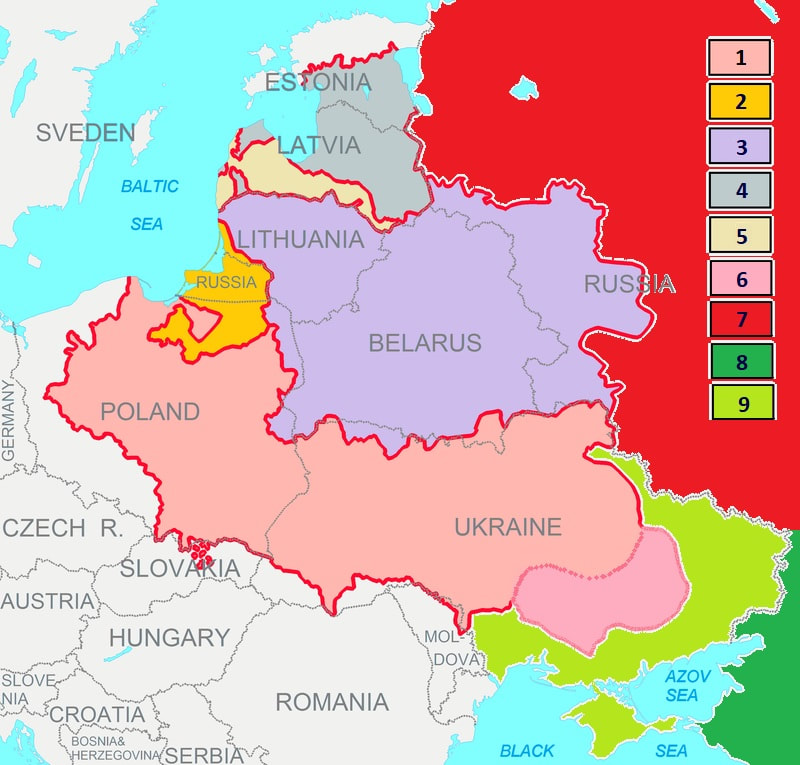

1813 engraving by E. M. Korneev. Above: Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1619. Legend: 1 - Kingdom of Poland, 2 - Duchy of Prussia - Polish fief, 3 - Grand Duchy of Lithuania (federated to the Kingdom of Poland), 4 - Livonia, 5 - Duchy of Courland - Livonian fief, 6 - "Wild lands" of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, 7 – Muscovite stardom (Russia), 8 – Ottoman Empire, 9 – Khanate of Crimea and Turko-Tatar possessions (Ottoman vassals). Borders and names in grey indicate present day states. Map by Dgreusard, Bogomolov.PL and Claude Zygiel , CC BY-SA 4.0 licence; modified by N&C cartographic division.

|

Who could be more associated with images of Russia than Cossacks? Yet the territories in which they formed as a distinct people are exclusively Ukrainian and are the basis of the first independent Ukrainian state. At the end of the Middle Ages and during the period of the Renaissance, the extremely diverse bands who were to become the Cossacks, settled what had become by then, like many other parts of Eurasia, a zone quasi-deserted by the ravages of invasions from Asia, the Black Plague and clouds of locusts. It was called “the frontier”, the land “the border”. In Ukrainian the name is pronounced “Ukra-Ï-na”. After being used for centuries in different Slavic languages to indicate a variety of specific regions or vague borderlands Ukraina began to appear in various documents as the name of the lands located in the Dnepr and Don basins, and in particular, as the zone controlled by the Cossacks.

I remember many Cossacks who, like my grandfather Constantine Kobtzeff (from the Zaporozhians, one the core tribes from which the other Cossack bands originated), had fled the Red armies and gone into exile. One of the youngest of these exiles that I can remember (he was a child in 1920, the year of the great exodus from Ukraine), was a rough faced, bald, colossus who, in the late 1980s, in his old age, returned to school to write a thesis on the origins of the Cossacks. “I started gathering documents” he proudly announced to me in his stentorian voice, after a session of our graduate seminar in Slavic history at the Sorbonne. Our professor and mentor, Professor François-Xavier Coquin, was less enthusiastic. To the poor old and naïve man, he tried as diplomatically as possible to explain the difficulty of the task that he had assigned it to himself. To me in private, after difficult advising sessions, the professor lamented: “No one knows exactly who the Cossacks were. No one knows where they came from.” We can only speculate that their ancestors might have been a ragtag of runaway serfs from Russia (where the system of serfdom was rising in a very oppressive way), renegade Tatar warriors, runaway slaves from the Ottoman Empire, particularly from the nearby territories of the Khan of Crimea, deserters from the armies of surrounding states, and desperate wanderers leaving Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, Lithuanian, Tatar or Turkish villages ruined by war, climate change (the “mini ice age” of circa 1400-1800), crop failure, the Black Plague, and searching for a new land and a new life in the temperate add sunny climate of the eastern basin of the Dnepr and the western basin of the Don. Those lands had been ravaged by the plague and were now almost empty of inhabitants. The land had become a wilderness, a frontierland, on the borders of civilization. “On the border of…” is said “u kra-i-na” in several Slavic languages. How this frontier was settled by the Cossacks remains very obscure. What we know is the result in the 17th century: the settlers became ranchers and crop growers living as armed militia, each in a fortified settlement called sich. Each sich and clan had a very democratic form of self-government with an assembly (rada) and an elected chief called a hetman or ataman. Not unlike immigrants to the new world at the same time, they also seemed to value a strong sense of freedom. In the late 1400s and throughout the 1500s, the network of clans and fortresses progressively federated into one great Sich. Its growing independence as a proto-state was tolerated by the Kingdom of Poland or by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth because, on their borders of Asia, the Cossacks defended all of Catholic Europe against invaders from the East. The Cossack Sich, also known as the Zaporozhian Sich formed a large territory on the East bank of the Dnepr (called the Left bank because some representations place the South—location of the river’s estuary—on the top of maps), while the rest of Ukraine remained under the governors of the region (voivodship) of Kiev (called the Right bank). |

But a major difference existed between the Cossacks or other inhabitants of the Zaporozhian Sich, Kiev, or Belarus, and the rest of the subjects of the Kingdom of Poland and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: most ancestors of modern Ukrainians and Belarusians were Eastern Orthodox, not Roman Catholics. Since the mid-1500s, the Catholic Church was on a mission of reconquering the authority it was losing to the rise of Protestantism. The Counter-Reformation was essentially a missionary movement, and it was intimately related to the conversion of populations in the new colonies or Japan and China, building new churches, schools and new monasteries, encouraging new monastic orders devoted to educate and reeducate the populations of Europe that had been lost or were at risk of being lost to Protestant influence. This effort of spiritual and geopolitical Reconquista or plain conquista affected the Orthodox populations under Catholic rulers in Eastern Europe, particularly in Ukraine. In the westernmost zones of influence of the Orthodox religion, dozens of Orthodox bishops and their priests converted to Catholicism under the conditions of the 1595-1596 Brest Union (Unia in Latin-hence the expression “Uniates” to designate the converts) that guaranteed that the converted parishes would continue to hold services in the unchanged Byzantine ritual, in Slavonic, not Latin, and that certain canonical practices, such as married clergy, would be preserved. But these converts, whose descendants were 8.8% of the Ukrainian population in 2019, would remain a minority. The efforts by Catholic authorities to proselytize were counterproductive. They were perceived as a threat by most Orthodox populations in Ukraine, although their élites—clergy and lay intellectuals, aristocrats, Cossack leaders and merchants—were heavily influenced by a very Latin education in highly advanced local schools and universities in Lwów (Lviv) or Kijów (Kiev/Kyiv), and other cities. The pressure felt by the Orthodox Ukrainians from the Catholic Reformation in their lands, generated an Orthodox “counter-Counter Reformation” consisting mainly of monastic revival, printing, building schools and churches. Among the most significant achievements of Ukrainian Orthodoxy were the missionary work of Saint Iov (Job) of Pochayev, the printing of the Bible, and the creation of missionary-educational brotherhoods. The two most influential brotherhoods—the one in Lwov (the Polish name of the city, Lviv in Ukrainian) and the one in Kiev (now Kiow in Polish or Kyiv in Ukrianian)—had schools which, under the Archbishop-Metropolitian of Kyiev and all Ukraine, Petro Mohyla (1596-1647), merged in 1632. The new academy became Ukraine’s first university. Today, Kyiv’s university which will soon celebrate its 400th anniversary is named after this exceptional intellectual who had great ambitions for the education of not only Ukraine but all Slavic and Romanian Orthodox lands and is venerated as a saint.

At the same time, the labors of such figures as Iov of Pochaeyev and Mohyla were part of the rising cultural conflict which had considerably unsettled the order of society in Ukraine. It was to have severe political consequences. In 1648, the all-Cossack parliament, the Rada—the name used today by the Ukrainian legislative assembly—voted the independence of the Cossack lands from the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. Led by the Cossack hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyï, the bloody war that ensued was leading to the defeat of this first Ukrainian state. Its representatives then turned for help to the Russian tsardom, in return for which, by the treaty of Pereyaslavl’ of 1654, tsar Alexis (the future father of Peter the Great) obtained the allegiance of the Cossacks and the incorporation of their lands into Muscovy-Russia as a protectorate with a high degree of self-government. It is interesting to note that Bohdan Khmelnytskyï is still considered as a national hero in Ukraine as much as in Russia to this day. It was for the tricentennial of the 1654 treaty that under the leadership of recently appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian Nikita Khrushchiov (pronounce Hroo-SH-CHiov not “crude chef” as inevitably prompted by the inept but universally imposed transliteration “Khrushchev”), the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR separated Crimea from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and annexed it to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The Cossack lands then lost almost all their autonomy at the end of the 18th century under Catherine the Great. However, the individual settlements maintained their local form of self-government and the Cossacks faithfully served the Russian emperors with a loyalty ended energy that made them feared so much and also made them the target so the quasi genocidal cleansing in the Ukrainian territories conquered by the Red Army from the white army in 1919.

In the early 1700s, that part of Ukraine which was federated to Russia under the Pereyaslavl’ treaty of 1654, saw the famous Cossack chief Ivan Mazepa rise to power, becoming the quasi-ruler of the land. After a period of serving Peter-the-Great, Mazepa began to question his loyalty to the tsar. To serve the geostrategic interests of Russia, Cossacks troops were now being sent on military expeditions to remote lands, leaving their families exposed to attacks by Tatars and Ottomans from the East, and Poles from the West. Cossacks and Ukrainian peasants who also remained unprotected, lived in fear. Mazepa, with a faction of the local Cossack leadership came to the conclusion that the essential purpose of the 1654 treaty—submission to Russia in exchange for the tsars’ protection from Poles, Tatars and Ottomans—was being violated. The very ambitious Mazepa then brought his faction of dissidents under the authority of Swedish King Charles XII after this arch-enemy of Peter-the-Great launched a vast invasion of Ukraine in 1708, in conjunction with the Polish kingdom, aiming to attack Russia from the South-West. Tsar Peter defeated the Swedish army at the battle of Poltava, one of the most important turning points in Europe’s military and geopolitical history. It established Russia as one of the major world powers of modern times. Mazepa (who fled into exile) had only gained support of only a small minority of Cossacks. Their majority remained loyal to Moscow. One of their leaders, Vasil’ Kochubey, who was executed by Mazepa with another Cossack leader, Ivan Iskra, became a celebrated figure in the legendary poem Poltava by Alexander Pushkin, and another pro-Russian loyalist, Ivan Skoropadsky, became the new hetman of Ukraine. The reprisals against the settlements where most inhabitants had sided with Mazepa were extreme and tsar Peter's troops cared little about who were their enemies, who were their allies and who was neutral or was an innocent bystander when they carrying out their raids.

The Cossack lands then lost almost all their autonomy at the end of the 18th century under Catherine the Great. However, the individual settlements maintained their local form of self-government and the Cossacks faithfully served the Russian emperors with a loyalty ended energy that made them feared so much and also made them the target so the quasi genocidal cleansing in the Ukrainian territories conquered by the Red Army from the white army in 1919.

In the early 1700s, that part of Ukraine which was federated to Russia under the Pereyaslavl’ treaty of 1654, saw the famous Cossack chief Ivan Mazepa rise to power, becoming the quasi-ruler of the land. After a period of serving Peter-the-Great, Mazepa began to question his loyalty to the tsar. To serve the geostrategic interests of Russia, Cossacks troops were now being sent on military expeditions to remote lands, leaving their families exposed to attacks by Tatars and Ottomans from the East, and Poles from the West. Cossacks and Ukrainian peasants who also remained unprotected, lived in fear. Mazepa, with a faction of the local Cossack leadership came to the conclusion that the essential purpose of the 1654 treaty—submission to Russia in exchange for the tsars’ protection from Poles, Tatars and Ottomans—was being violated. The very ambitious Mazepa then brought his faction of dissidents under the authority of Swedish King Charles XII after this arch-enemy of Peter-the-Great launched a vast invasion of Ukraine in 1708, in conjunction with the Polish kingdom, aiming to attack Russia from the South-West. Tsar Peter defeated the Swedish army at the battle of Poltava, one of the most important turning points in Europe’s military and geopolitical history. It established Russia as one of the major world powers of modern times. Mazepa (who fled into exile) had only gained support of only a small minority of Cossacks. Their majority remained loyal to Moscow. One of their leaders, Vasil’ Kochubey, who was executed by Mazepa with another Cossack leader, Ivan Iskra, became a celebrated figure in the legendary poem Poltava by Alexander Pushkin, and another pro-Russian loyalist, Ivan Skoropadsky, became the new hetman of Ukraine. The reprisals against the settlements where most inhabitants had sided with Mazepa were extreme and tsar Peter's troops cared little about who were their enemies, who were their allies and who was neutral or was an innocent bystander when they carrying out their raids.

The Cossack lands then lost almost all their autonomy at the end of the 18th century under Catherine the Great. However, the individual settlements maintained their local form of self-government and the Cossacks faithfully served the Russian emperors with a loyalty ended energy that made them feared so much and also made them the target so the quasi genocidal cleansing in the Ukrainian territories conquered by the Red Army from the white army in 1919.

The rest of Ukraine was progressively annexed by Catherine the great as the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth was dismantled by Russia, the Austro-Hungarian empire, and Prussia. Although Ukraine was now completely annexed it was expanded, nevertheless, while remaining a part of the Russian empire, by the conquering of large Ottoman territories beyond the southern borders of Ukraine and mainly by the annexation of the Tatar khanate Of Crimea, Which not only included the Crimean Peninsula itself but the vast prairies northwest of the sea of Azov and between the East side of the Don estuary and the Caucasus. Together, Ukrainians and Russians and other subjects of the empire developed those lands, built entire navies on the shores of the Azov and Black Seas, and founded and populated the ports of Nikolaev (Mykolaev) Kherson, Odessa and Sebatopol. Together, a few years later, in 1812, they fought bloody battles defending Belarus, then muscovy against Napoleon. Together, losing nearly 400,000 men, they defended Crimea against the armies of another Napoleon and his British, Ottoman and Italian allies. The heroes of the defense of Sebastopol, Ukrainian sailors Koshka, Bubyr’, and Shevchenko, are celebrated to this day by both Russia and Ukraine by many monuments, in the naming of streets, on stamps and in many other public manifestations. Russians and Ukrainians fought in all the wars of the empire and of the Soviet Union particularly in the war of independence of Bulgaria, in the Russia Japanese war, and in both world wars. Russians and Ukrainian as Whites (including almost all Cossack regiments), or Russians and Ukrainians as Reds, fought side by side in the opposing factions in the civil war that followed the 1917 revolution.

BACK TOGETHER AGAIN: A COMMON HISTORY OF 337 YEARS

Together they built modern Russia, its railroads, its factories, its mines, its shipyards, its airports, its research centers, its universities, and administered the tsarist empire and the Soviet Union (three out of the five General Secretaries of the Communist Party of the USSR who succeeded to the Georgian Stalin were Ukrainian—Khrushchiov, Brezhnev, and Chernenko—while Gorbachiov’s roots in the Stavropol’ region, a historical colony of the Cossacks, and his accent in Russian were characteristic of strong ties to Ukraine).

|

Any Ukrainian would proudly present Nikolay Hohol’ as the second greatest Ukrainian writer of all times after Shevchenko the Ukrainian poet of all times. He is known as “Gogol” worldwide through the Russian pronunciation of his name. Vladimir Nabokov, author of Lolita and of the best biography ever written about Gogol/Hohol’ would give me a bad grade in his literature class if, instead of decoding the purely structural, verbal and poetic complexity of Gogol’s genius, I focused on his Ukrainian short stories. But the collection of stories from the Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka and the novella Taras Bul'ba are far too rich in observations on Ukrainian daily life, society and folklore to be rejected by the historian that I am. So many Ukrainians know more about their culture from reading the stories of Gogol than from observing their country from the windows of their high-rise apartments in an urban environment as standardized, as lacking in personality as any poor suburb of Paris or as the “projects” in Baltimore. But Gogol’s representations of his native Ukrainian countryside are also a foundation of the Russians’ national iconography.

The same can be said about the landscape paintings of romantic artist Crimean born Armenian Aivazovskiy (Ayvazyan) and of his student of Crimean Tatar and Greek origins Ukrainian Arkhip Kuindzhi, a more modern painter. Aivazovskiy’s rhythmic of waves exploding over tormented Crimean cliffs and Kuindzi’s spellbinding quiet panoramas of the shoreline of the Dnepr in the sunset are breathtaking for both Ukrainians and Russians and all other former inhabitants of the tsarist empire or of the Soviet Union for whom painters like these were almost like a shared secret since they were almost completely unknown West of the Polish-Belarussian border. The landscapes of Crimean born painter Armenian Aivazovskiy and of his student of Crimean, Tatar and Greek origins Kuindzhi, born in Mariupol, are breathtaking for both Ukrainians and Russians and all other former inhabitants of the tsarist empire or of the Soviet Union for whom painters like these were almost like a shared secret since they were barely known in the West .

|

Above: "The Black Sea" by Aivazovsky. Below: "After the RAin" by Kuindzhi.

|

Such cultural transfers occurred between the 10th and the 14th century when all the territories of Rus’ were ruled by Kiev then between the middle of the 17th century and 1991 when they were ruled by Moscow or Saint Petersburg. Roughly, that is more than seven and a half centuries of common history and cultural mixing. That is five and a half more years than the common history between Texas and the states northeast of Washington D.C. So why is it that no one is disturbed by a Texan proclaiming that he is both Texan in American while a Ukrainian who speaks Russian as a mother tongue or, worse, considers himself or herself as both Ukrainian in Russian are seen today in great suspicion throughout western public opinion and media? how can we represent Ukraine as a country to which Russians are a completely alien and invasive species using such expressions as Russian occupation of Ukraine as if this was Nazi Germany occupying France in 1940 nineteen 44? How can US foreign policy makers frequently base their pronouncements on such representations?

But the other problem today is that there is another side to the idyllic narration of a Russian-Ukrainian common destiny. And modern Russians refuse to see it.

But the other problem today is that there is another side to the idyllic narration of a Russian-Ukrainian common destiny. And modern Russians refuse to see it.

Not such a happy family.

“The Ukrainians are our brothers, we share so much of the same history and culture”, proclaimed with emotion the Russian ambassador to Brussels during a peace conference which I attended there as a panelist. In another conference, this time at the Grenoble University, I heard another Russian diplomat, this time from Marseilles, also talk about the kinship between Russians and Ukrainians and how it was impossible for a Russian to go to war against these brothers. This was said soon after the annexation of Crimea. The opponents of these Russian diplomats would then logically question Russian support for separatists in western Ukraine who started a conflict where the body count was rapidly rising to nearly 5000 after only a few weeks of combat. Granted, many of the civilian victims were also bombed by the Ukrainian army and the Russians would be logical in replying that since the late 1980s, any separatism from of any region claiming independence from Russia or from any of its allies is immediately supported by the West in the name of the principle of self-determination of nations, whereas a smaller region wanting to separate from those newly independent countries would immediately be demonized as violating the sacrosanct sovereignty of any pro-Western ex-Yugoslav or Soviet Republic. But that wouldn't explain why such a large majority of Ukrainians wanted independence in the first place and are happy to have it now, and are ready to defend it with such determination. It is not just weapons provided by the West that have been preventing the Russian federation's troops advancing further West, it is the defense of a certain idea of Ukraine. Whatever strong bonds existed before between Russians and Ukrainians, like once existed between the Natives of the British isles and the British settlers of the 13 colonies South of Canada, through this armed struggle, we are witnessing the emergence of a new modern Ukraine completely separate from Russia.

The factors are not recent.

While it is highly exaggerated to talk about a Russian colonization or “occupation” of Ukraine, after the full annexation by Catherine the great, the land was not treated as an equal partner. We can at least compare the treatment of Ukraine to how Scotland was treated by England and, how Hungary was treated by Vienna. The only Ukrainians to become fully equal to Russians were the aristocrats. In fact, except for the Cossacks who were able to continue ruling their villages in a traditional way (but now without the national Rada or anything of the sort), the peasants lost much of the few freedoms they had under Polish-Lithuanian rule once they became part of a rigid Russian economic and political system based on serfdom.

There was no administrative measures of discrimination against Ukrainians for being Ukrainian, like there were against Jews. However, informal humiliations were numerous and frustrating. Russian representations of Ukraine in song, literature, the indigenous population, suffered a number of